Marcus Richardson Searight (1826-1898)

Marcus was born in the Newry area about 1826, to Edward Seawright and Mary ???. Edward is listed as being a resident of Poyntzpass in 1838.

Marcus became a police constable, and by his early 20s was stationed in Co Antrim. In June 1851 he married Mary Jane Knox at Dunluce and they eventually had ten children, most of whom were born in counties Antrim, Londonderry or Donegal. They are:

- Marcus Jnr 1855 – 1886

- George H 1856 – ???

- James 1857 – 1875

- Mathilda 1862 – 1893

- David 1868 – 1869

- William 1868 – 1902

- Henry 1869 – ???

- Mary 1869 – ???

- Joseph 1872 – 1925

- Annie 1876 – 1902

It is notable just how many of Marcus’s children died relatively young.

Marcus was still a constable when he retired from the Royal Irish Constabulary, on a pension of £31 p.a., paid monthly. He received his first payment in March 1871, when he was aged about 45, in Londonderry. By 1885, this is recorded as being paid in Portadown.

We do not know whether Marcus and his family moved to the area at the time of his inheritance from Jane, or before it.

Multiple Family Disputes

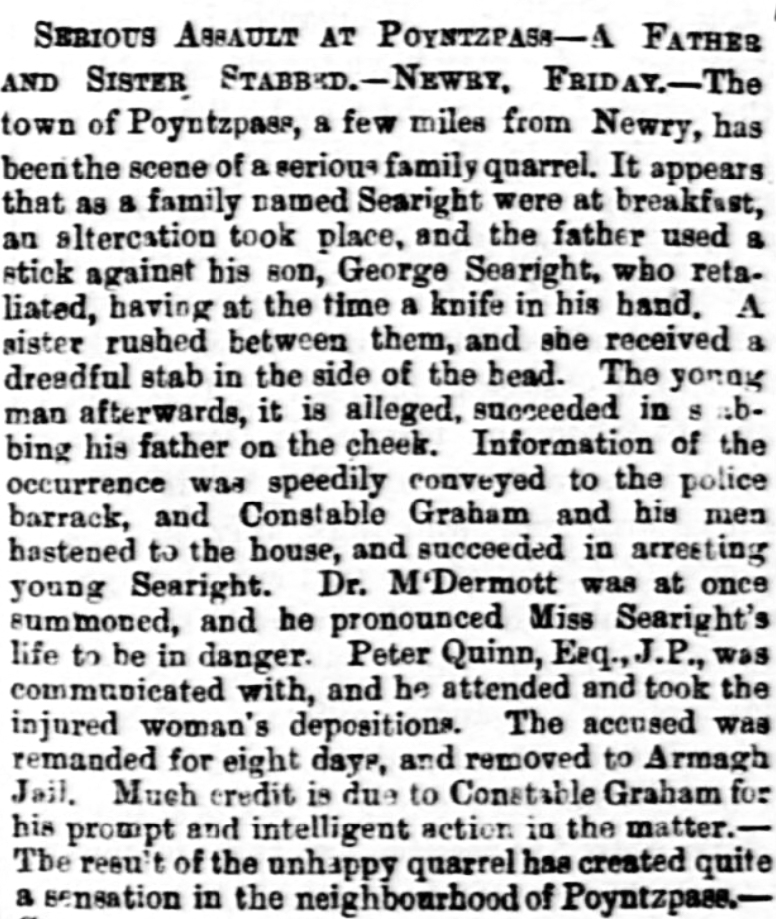

The first record of them living in Poyntzpass is a newspaper report describing a vicious fight between Marcus and his son George, then aged about 23, on 13th November 1879. It was reported in newspapers throughout the UK.

The Miss Searight was Marcus’ daughter Mathilda, then aged about 17. She certainly survived the attack, but died in 18931 of TB, aged about 31. After already spending two weeks in gaol, George was brought before magistrates2; Mr. Miller bound him over to keep the peace for a further 12 months.

Marcus’ sister Jane Whigham died in January 1879, aged 69, and left the property to him; he was aged ~53. As we shall see, she made a grave mistake in making him the executor as well as the main beneficiary.

Marcus Inherits The Property

Marcus had obtained probate on 6th November 1879, just a few days before the fight. Perhaps there was an argument over the inheritance? It is possible that at the time of the fight, Marcus and his family had not yet moved into the house.

The probate records list the value of Jane’s estate at “Less than £1,000”. Marcus was sole executor and was also principal beneficiary. Jane’s will also stated that Marcus should pay £200 (over 20% of his inheritance) to their sister Elizabeth within four months, but Marcus did not, and used a clearly immoral (but perfectly legal) ploy to get round this bequest.

Marcus Cheats His Sister

At that time, under Irish law, everything that a woman nominally owned was actually owned by her husband. Elizabeth was married to one William John McCreery, but he had abandoned her some time before 1879, and was providing no money for her upkeep. Marcus reasoned that despite this, the courts would recognise McCreery as being legally entitled to Elizabeth’s money and so he paid McCreery a mere £30 to sign a document renouncing any claim to the £200, and also appointing Marcus as McCreery’s attorney.

How he persuaded McCreery to settle for £30 instead of the full £200 is a mystery. His defence included the assertion (totally unfounded as far as we can tell) that Elizabeth had exercised undue influence over Jane. He could have contested the will but reasoned that this strategy would be a lot less risky, and much cheaper.

Elizabeth clearly believed that Marcus’s refusal to pay her her sister’s bequest was outrageous, so in 1880 she sued her brother for the £200, naming Marcus and McCreery as co-defendants. The court case of “McCreery vs. Searight” was heard in the Chancery Division in April-May 1880.

The legal judgment was complex and is riddled with arcane legal language – but in summary not only did Elizabeth lose the case but she also had to pay Marcus’ and McCreery’s costs, as well as her own, which would have been substantial as both sides were represented by Queen’s Counsels.

So Marcus not only benefited to the tune of £170, but he also made Elizabeth pay for the privilege of being fleeced! The Married Women’s Property Act had been passed in 1870, ten years before the case was heard, but did not apply retrospectively, if the couple had married before the act became law. No doubt if it had been retrospective, a lot of very rich people whose fortunes relied on the rigid rules of inheritance would have been very upset!

In October 1880, Marcus was granted the transfer of the wine & spirt licence for The Railway Hotel (it is not recorded from whom, but presumably from Jane Whigham).

Marcus’ Final Years, And His Will

Marcus’ wife Jane died in October 1890, aged 63. In October 1893, Marcus married3 again, to another Jane – Jane Thompson from Crankey, near Tannyokey. Marcus was now 67 and Jane was probably aged about 43. On the marriage certificate his occupation was recorded as coal merchant.

Marcus died of a stroke on 27th December 1898. His death notice appears to have been widely publicised in Irish newspapers including The Ballymena Weekly Telegraph along with the rather odd phrase “American papers please copy”. This typically indicates that close members of the family had emigrated to the USA in the years following the great famine, but they had lost touch.

Marcus left a total of £935, remarkably close to the sum he inherited from his sister 20 years earlier.

George Gets Nothing

Probably because of the 1879 fight, George was very much persona non grata with Marcus. In his will, dated 1894, Marcus leaves “all my houses, land, stock in trade, cattle, furniture and cash” jointly to three of his four surviving sons – Joseph, William, and Henry. His two surviving daughters Bessie and Anne receive one shilling each4 “as they are already provided for” (presumably because they are married).

He also leaves George a shilling “as he received his share and merits”. I take this to mean that it is all that Marcus thinks George deserves – George is effectively being disinherited. The device of leaving just a shilling to a person was a common method of preventing claims on the estate of the deceased by people who thought they had a claim; it says “I didn’t forget you – but I decided you weren’t worthy”. He also leaves one shilling to “my son Marcus (deceased) to exclude his wife and heirs, if any”; Marcus Jnr had died from TB aged just 31.

Marcus Cuts Off His Second Wife

His second wife Jane (Thompson) was also only left one shilling “as she is otherwise provided for”. It is unclear what this means and also seems rather over-optimistic. Just over two years after Marcus’ death, the 1901 census records Jane as once more living in Crankey – widowed, a seamstress and head of household. Also living with her are four of her nephews and nieces, aged between 11 and 19 – perhaps they were orphans?

By the 1911 census, Jane was once more living alone, still in Crankey and now listed as a farmer. She died in June 1923 aged about 73. Her total estate was a mere £16 5s 3d which she left to her bother William, a Belfast chauffeur. Yet another victim of the ruthless Marcus.

The Close Estate rent book records for November 1901 show the annual rent of the property, Account no. 349, payable by the Representatives of Marcus Searight, as £13 17s 8d … exactly what my father paid each year from 1934 until 1969!

1901

The 19015 census lists the following as living at the property:

| William Searight | Head of Family | Publican | 33 | Married | Born, Co Donegal |

| Annie Searight | Wife | — | 25 | Married | Born Co. Armagh |

| Joseph Searight | Brother | Assisting partner? | 24 | Single | Born Newry |

| George H Searight | Brother | Commercial Clerk | 45 | Single | Born Co. Kerry |

In 1907, Annie is listed as a signatory to one of the many petitions between 1900-1910 about the state of the sewers in the village, and is listed as ‘general merchant’. It is not clear what premises she was operating out of.

William Searight

In December 1897, the Belfast News-Letter records William as one of those in Poyntzpass who have donated one shilling (5 pence!) towards the cost of a new statue of Queen Victoria to be erected in Belfast.

William did not long outlive his father. He married Margaret Ann Poole (Annie) in June 1900 but died on 5th August 1902, aged just 34 in 1902, leaving no children. Annie subsequently remarried, to Robert Allen, and had two children, Robert and David.

Despite his young age, William seems to have prospered, but clearly the Railway Hotel was not doing o well; William’s will states:

“I also give her [his wife Annie] all the money due to me by the Railway Hotel which I have advanced of my own private money to meet the demands, the profits of the place not being sufficient as the books will show (at the time of writing the Will [January 1902] it owes me almost £200)”.

William clearly thinks, as Marcus did, that his brother George is a wastrel.

“I give to my brother George H the sum of one shilling, his merits”.

Other parts of William’s will are fascinating. He also bequeaths to Annie …

“… my gold watch and chain (gold) and all the silver, gold and jewellery I have in stock for sale, also my photographic apparatus, including camera … clothes, books, four glass vases with stuffed birds in them, Singer sewing machine, Barometer clock, & all the clocks that I have for sale…”

To Joseph he bequeaths:

“… my bicycle that is the one that I last purchased or (in other words) his choice of any One Best Bicycle of mine … all they tools that I have for repairing bicycles … the carpenter’s tools that are mine…”

Henry is given:

“… my fowling pieces and ammunition pertaining to them such as recapper6 and turnover7”

So William is selling and repairing bicycles, selling jewellery, clocks and watches, lending money to his brothers and to others, and enjoying photography and wildfowling. Presumably the commercial activities are being run from the Railway Street premises adjacent to the hotel?

After William’s death, the sprits licence for the premises was transferred to Joseph in October 1902.

However, in a report carried in the Newry Reporter in January 1909, Annie Searight is listed as a signatory to yet another letter, dated 11th November 1908, protesting the state of the sewers. Annie is listed as a “general merchant” and Joseph was also a signatory. Were Annie’s premises still in our house?

Henry Searight

Henry married Annie Purdy on 27th June 1900, when he was 30, and by 1915 they had eight children. He is listed on his marriage certificate as ‘hotel proprietor’ (his 1/3 share in the Railway Hotel) and was by then also running the Cyclists’ Bar in Church Street, close to the former Waddell & Mallie pharmacy.

In August 1911, Henry put the Cyclists Bar up for sale; it was bought by George McClements … whose wife Maria later bought the coal business in 1919. However, the licence wasn’t transferred from Henry’s name until February 1913 – to one Patrick McKeown. It finally closed in 1954, when it was bought by the McVeigh family and became a private house.

Henry and his family later moved to Belfast, where he lived for some years at 31 Templemore Avenue. We do not know when he died. Annie died in 1961.

Joseph Searight

Joseph appears to have taken over the day-to-day running of the Railway Hotel set of businesses.

In September 1902, he applied to have the spirit licence for the Railway Hotel transferred from William, who had died the previous month, to him, saying in his application “… interest in such licence having duly been assigned to me”.

Oddly, on 21st July 1904 an advert appeared in the Belfast Telegraph, “WANTED: a Situation as General Man on Farm; capable of all classes of farm work; Protestant; single; Apply Joseph Seawright, Railway Hotel, Poyntzpass”

In August 1907, he was fined 10 shillings at Poyntzpass Petty Sessions for having failed to admit the police to the premises at 9pm on the evening of 13th July. There were, according to the police, “a number of drunken parties about the roadway”.

Adverts regularly appeared in newspapers in the early 1900s listing Joseph as one of the many agents for steamer tickets to England and even to the USA and Canada, so he was also a sort of early travel agent.

By the time of the April 19118 census, the resident population at the Railway Hotel is quite different from 10 years earlier:

| Joseph Searight | Head of Family | Publican | 38 | Single | Born, Derry City |

| Rosia Irwin | — | Barmaid | 24 | Single | Born Co. Meath |

George H (who would have been 55) seems to have completely disappeared from the public record. The only adult George Searight anywhere in Ireland in the 1911 census is in Co. Kildare and is the wrong age. Had he died or perhaps emigrated?

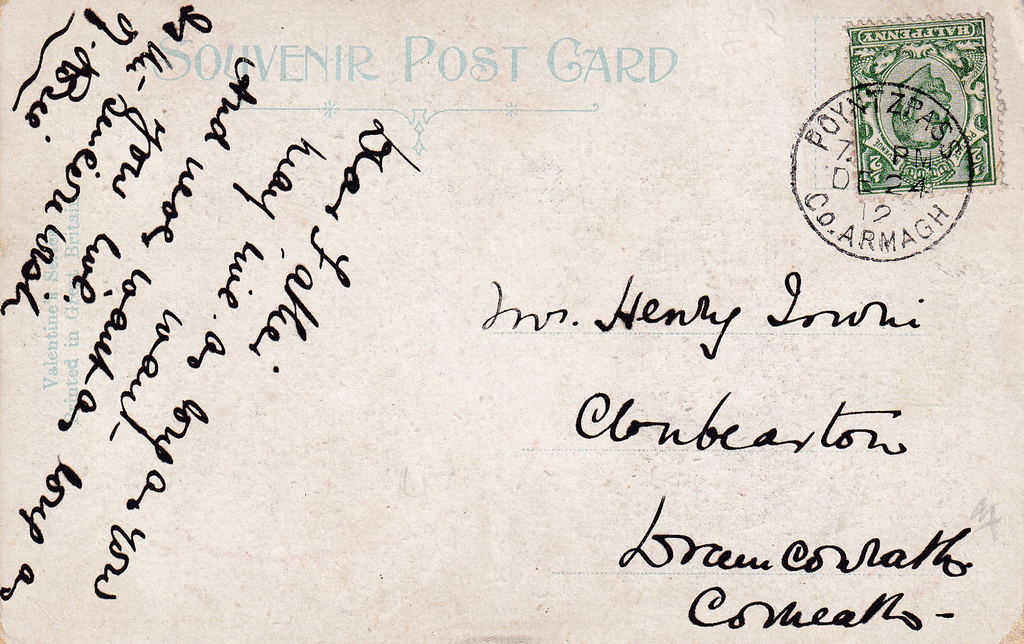

In 2021 I was browsing online, for more historic picture postcards of Poyntzpass. I spotted this one – and quickly realised its significance and bought it.

It is postmarked “Poyntzpass, 7pm, Dec 24, 1912”. Rosie, Joseph’s barmaid, was sending her father in Co. Meath a Christmas card…at the last possible moment! 😊

Note the upside down stamp; Rosie was catholic, and this was a common form of anti-British protest against the colonial power.

Rosie either had a poor memory or lied about her age – she was born on 29th January 1880, so was actually 31, not 24, at the time of the 1911 census!

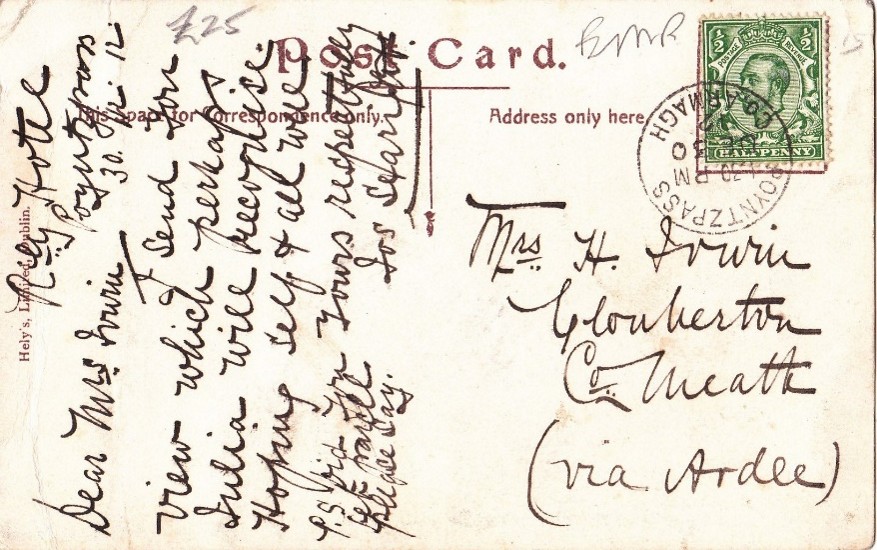

Remarkably, we also have an image of a postcard sent by Joseph Searight to Rosie’s mother just a few days later; it is postmarked 30 Dec 1912, and is clearly a new year card. It It reads

“Railway Hotel, 30-12-12. Dear Mrs Irwin, I send you [a] view which Julia will recognise. Hoping self & all well. Yours respectfully, Jos. Searight. PS Bid you [illegible] please say.”

Joseph & The Sewers

There are many reports of Joseph in the local press around 1911-12, when he was a prominent player in the ‘Great Poyntzpass Sewer Disputes’, which had been going on for over a decade, spearheaded by Dr MacDermott. Such drains as there were in the village in the first decade of the C20 were grossly inadequate, and the sewage was not treated but simply discharged (into the canal?).

A very small stream called the county drain ran alongside our house, on the precise border between Armagh and Down… and the border of ‘the Far Pass’. When I was a child, this tiny stream (no more than a trickle) flowed on the surface between our house and Cairns’s house; it was often a quagmire! My father had it culverted sometime in the 1960s at his own expense and created a pleasant small side garden in its place.

The problem for Joseph was that all of the surface water (and worse!) from William Street ran straight down the hill and hit the wall of his house. The drain should have coped with it, but it was often blocked and Banbridge and Newry No 2 RDCs constantly bickered about whose turn it was to clear it. The ubiquitous Dr MacDermott was involved too, of course – he inspected and reported on the drain several times.

The last newspaper report featuring Joseph and the drains was in October 1911.

Joseph Gets Married

Joseph married Catherine Barry, a nurse and midwife, in Cirencester on 10th September 1913. Her widowed mother ran the Black Bull Inn there.

So, did Joseph already know Catherine? If so, how? Did he simply travel to Gloucestershire for the wedding? There was an Irish connection – Catherine’s father, Richard Barry, was born in Mallow, Co Cork, but was living in Cirencester by the time he was 22. Catherine was born in 1888, but her father died when she was only five years old.

Joseph and his new bride must have returned to Ireland almost immediately, as “Mrs. Joseph Searight” is mentioned in a Newry Reporter article about the Acton Parish Church annual Harvest Service of 17th October 1913, just over a month after the wedding.

In March 1915 their son (another Marcus Richardson Searight) died in Poyntzpass from pneumonia, aged between one and two, with Catherine in attendance. Had theirs been a shotgun wedding? The child must have been conceived no later than about July 1913 – the wedding was about 3 months later.

Joseph Moves Away And Sells The Property

Joseph and Catherine later moved to Moss Side, Manchester, either leaving the premises empty or sub-letting it. Joseph decided to sell the Poyntzpass property, and it was put up for sale by public auction on 3rd June 1919. We do not know whether the move to Manchester was before or after the sale.

The comments about the proximity of the canal are somewhat misleading, as any form of canal-based trade was by then almost on its last legs. And as for hot and cold running water, the water mains had still not been installed in the village.

Joseph and Catherine appear to have divorced in the early 1920s, and she remarried a Mr Dean. At some time after his divorce, Joseph moved back to Belfast.

Joseph, The Minor Fraudster

The Belfast Telegraph carried a report on 16th April 1924, where a man called Joseph Searight of Prince’s Street9 Belfast appeared in court accused of an insurance scam – he reported his insured keys as being lost, then pretended to be someone else (the minimally disguised “J C Wright”!) and returned then in exchange for the reward. The keys were sent back to him by post, but he dids not acknowledge them, asserted that he never received them and then further claimed for the expense of travelling to Poyntzpass and hiring a locksmith.

The Poyntzpass connection makes me pretty sure this is ‘our’ Joseph Searight; it seems likely that by that stage there was nothing in Poyntzpass that he still had keys for and that he didn’t make the journey. The locksmith testified at the trial that he had only given Joseph a written estimate but not done any work for him in Poyntzpass. This appears to be the second time that Joseph had carried out the same fraud.

A report in the Belfast News-Letter dated 14th May confirms his identity, as having previously run a hotel in Poyntzpass and reports that he was sentenced to one month in prison. In passing sentence, the judge advised him that he should “give up this sort of thing”.

Just over a year later, Joseph died in Belfast City Hospital at 51 Lisburn Road10, Belfast, on 1st September 1925, aged 52. We don’t know the cause of death.

There was still at least a Searight association with Poyntzpass as late as 1944, when Norman and Billy Searight were listed as mourners at the funeral of Mrs Sarah Purdy. They were Henry Searight’s two sons; their mother was Annie Purdy and the Mrs Purdy who died was most likely their grandmother, Mary Jane. The report says her husband survived her; if so, he would have been about 96 at the time of her death.

- Some uncertainty – headstone says 1895, other records differ. ↩︎

- “Return of crimes .. reported by Royal Irish Constabulary, March 1878-December 1879”. We don’t know which magistrate’s court George appeared at. ↩︎

- One of the witnesses was Edward Searight, a grocer. We don’t know what relation he was to Marcus. The only Edward Searight alive in Ireland eight years later at the 1901 census, was a printer’s compositor from Methuen Street, Belfast. ↩︎

- The leaving of one shilling to someone, in almost all wills that I looked at from the second half of the C19, appears to be a way of preventing a claim on the estate by someone who was omitted from a will but might normally have expected to be a beneficiary. It shows that they had not been overlooked; on the contrary have been actively considered … and rejected! Sometimes, a shilling was even left to a deceased family member, presumably to prevent claims from their descendants. See also “Wills” by Jimmy Clulow, BIF Vol 8, 2000. ↩︎

- It is interesting that by the early 1900s, almost all newspaper reports use the spelling Seawright, as does Joseph on his 1902 sprit licence application. However, the signage on the Railway Hotel and coal shed in Napier’s Edwardian-era postcards use the Searight spelling. ↩︎

- A tool used for applying a fresh percussion cap or primer to a cartridge shell in reloading it. ↩︎

- A tool used to reload a used cartridge. ↩︎

- The 1911 census entry for Poyntzpass also lists five individuals whose house number is given as ‘ship’. Three are listed as ‘lighterman’ and two as ‘trawler’. They must have been living on barges tied up opposite our house on the date of the census. See “The Last Voyage of The Nora” in “Before I Forget” Vol 13. ↩︎

- Joseph’s address at the time of his death was recorded as 56 Waring Street Belfast. ↩︎

- Formerly the site of the Belfast Poor House. ↩︎