Modern county and district councils in Ireland were only created at the very end of the 19th century. For most of the previous two centuries, the business of local government was largely conducted through the grand jury system. My account draws heavily on the 2021 booklet “People, Place And Power; The Grand Jury System In Ireland”.

As their name suggests, grand juries had long been integral to the Irish justice system, but by the 1820s, their duties and responsibilities had grown far beyond their original purpose of just determining whether an accused had a case to answer; they had become the de facto local government of Ireland.

Roads From 1615 – 1765

From 1615, the maintenance of roads1 had been the responsibility of each parish, with each adult male required to provide six days labour each year to maintain them. The established church proved to be inadequate in enforcing this statute, and under a law of 1705, parishes which failed to do so could be prosecuted and overseers could be appointed by the country grand jury.

Grand Juries Become Responsible For Roads

In 1765, legislation gave these grand juries the power to:

“…present such sum or sums of money, as they shall think fit, upon any barony or baronies in such county for the repairing [of] old roads or making new roads…”

They were responsible for the setting, collecting, and spending of the county ‘cess’ (rates), and from the 1830s they appointed (and their members often sat on) the Boards of Guardians of the Poor Law Unions responsible for workhouses and dispensary doctors.

They also approved expenditure for maintaining existing roads and the creation of new roads through the presentment2 system, ran the county gaols and from the early 1800s oversaw the fledgling police force. A small number of permanent officials carried out administrative functions from one grand jury sitting to the next.

Spring & Summer Assizes

Judicial assizes were held twice a year – in the spring (usually February or March) and summer (July or August). Each county had a high sheriff appointed by the government in Dublin and drawn from the ‘the great and the good’ of the county. The appointment was only for one year although many individuals held the post several – some many – times during their lifetimes.

The Panel List – The County’s Elite

Among the high sheriff’s duties were maintaining the Grand Panel List of landowners and others (typically 40-50) of high standing and status from which the members of a grand jury could be chosen at each assizes and liaising with the judicial authorities to determine the precise dates for the county assizes each year. This latter task was not trivial, as the number of trials, and the severity of the charges, and therefore the number of days the jury would have to sit, varied hugely from one assizes to the next.

Catholics were banned from sitting on grand juries until 1793; even after that date, very few did, partly through religious prejudice keeping them off panel lists, and partly because so few were big enough landowners to qualify.

The grand panel list of those ‘qualified’ to sit on a grand jury, which the high sheriff drew up each year, was largely determined by wealth; in essence, how much land you owned. The panel list was a political minefield. It mattered immensely to an individual of high status where on the list his name was (it was always ‘his’, of course) as it was really a proxy for where you stood in the county hierarchy.

Whether a landowner near the top of the list participated in a particular assizes and grand jury or not was largely his own choice. On the opening day of an assizes, all those who wanted to be selected for the grand jury simply turned up at the county courthouse. The high sheriff then read out whichever names he wished from the grand panel list and anyone answering when his name was called was automatically selected for the jury.

The sheriff did not have to justify his choices but had to ensure that the final jury contained at least one person from each Barony in the county. The process was complete when 23 jurors (or fewer, if no-one else answered to their name) had been selected.

The Summer 1844 Grand Jury

In Armagh Museum we can examine the panel list for the 1844 summer assizes, drawn up by John Robert Irwin of Carnagh House, that year’s high sheriff. The first ten names on Irwin’s list are, in order:

- The Earl of Gosford of Gosford Castle

- William Verner MP of Churchill

- Sir Henry Caulfeild of Hockley

- The Count de Salis of Tandragee

- Maxwell Close (Lt. Col.) of Drumbanagher

- Sir James Stronge of Tynan Abbey

- Marcus Synnott of Ballymoyer

- Maxwell Cross of Dartan

- Barnet McKee of Markethill

- Thomas Irwin Hamilton of Jonesborough

The list of the members selected for each grand jury was widely published in the local newspapers, as was the order in which they were selected. In this sitting, none of the first four were called (presumably because they failed to attend) and the other six were. Sir James Stronge was foreman and Maxwell Close was his number two. If the prominent citizens high on the list had attended, but had not been called, it would have been seen as a very public slight.

Circuits and Circuit Judges

Adjoining counties were grouped into circuits, and twice a year the judges travelled from one county town to the next by private coach, accompanied by mounted police. Armagh was part of the North East Circuit, which also included Drogheda, Dundalk, Monaghan, Carrickfergus and Downpatrick. A circuit judge was addressed by the archaic title ‘Baron’.

Once the grand jury had been sworn in, the presiding judge invariably opened proceedings by addressing the jury, and those members of the public present, on the state of law and order in the county. This address seems to have come in two basic flavours:

- “I congratulate you on the state of affairs in the county; it is very law abiding and there are few cases to try.” or…

- “Things look grim! We have many very serious cases to try; how did matters get so bad? We must restore law and order!”

Judicial Duties

The first duty oif the grand jury was to examine the cases of all those who had been remanded in custody since the last assizes, accused of a criminal offence. The grand jury’s job was, in each case, to determine whether the accused had a case to answer and should be sent for trial; if they did, this was known as ‘returning a true bill’.

Roads & Other Duties

After legal business was completed, the grand jury’s next task was the consideration of presentments for expenditure, mainly on public infrastructure, and especially road building and maintenance. The presentment system gave some parts of Ireland a dense network of public roads which were the envy of foreign travellers.

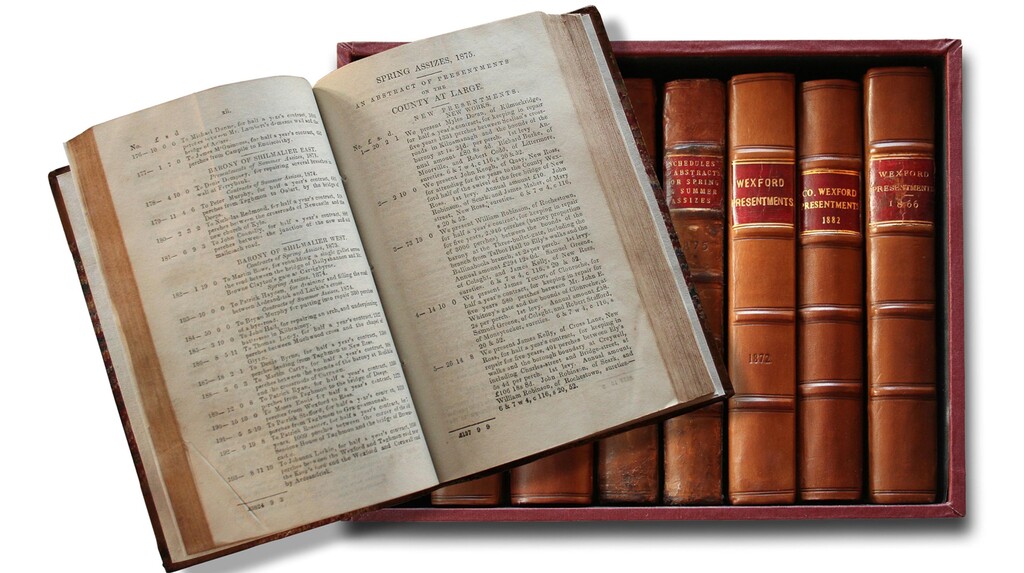

Presentments

McCutcheon (1980) gives an excellent account of the presentment system, and Herring summarises it thus…

“…. the presentment and indictment system of road upkeep throughout England…[was] extended to Ireland in the early seventeenth century, a method by which the justices of the peace took criminal proceedings against a parish for neglecting its roads. There were numerous revisions of the Irish presentment system in the early nineteenth century, but its essentials may be summarised as follows.

“Any person wishing to extend a road presented attested plans, maps and estimates to the magistrates in petty session; if they accepted, the project went before a grand jury for a final decision; once the grand jury had passed the scheme, the petitioner built the road at his own expense; later he presented a signed certificate of expenditure to the grand jury, which, after proper examination of the work, ordered the county treasurer to reimburse him out of the county cess. Presentment roads had to be at least 21 feet wide with 14 feet of stone or gravel.”

Jon Carr in ….. describes it in more detail:

“Whoever wishes to mend or make a road has it measured by two persons, who swear to the measurement before a justice of the peace. A certificate, containing its description, and the sum per perch which it will cost, is signed by the measurers and by two overseers who are also sworn to the truth of the valuation.

“This certificate is laid before the grand jury, at the assizes, and allowed or rejected by vote. If the certificate is granted, the applicant, at his own expense, must finish it by the ensuing assizes, when, upon his sending a certificate of his having expended the money properly, it is signed by the foreman, who also signs an order on the treasurer of the county to pay the applicant.

“This sum is raised by a tax on the land, which is adjusted by officers called applotters, who rate the estates acreably. This method, which has certainly much in it to commend, has also, like every human institution, much to guard against. The money raised by grand jury presentments is not always paid to the persons who make the road, such as persons being too frequently under the grinding oppression of the owner of the land through which the road runs, or his agent, in consequence of their being his tenants, and owing an arrear of rent, or being indebted to the agent for the purchase of a horse, cow, or pig; which rent or debt is frequently liquidated by the debtor making or repairing the roads, which is called road-money; a system which is frequently pregnant with the most cruel grievance.

“The affidavits also of the overseers have sometimes been signed by, without being having been sworn before, the magistrate, and the money for making the road has been paid without the road having been made: these facts were developed at a trial…in the county of Donegal. Such a system of fraud might be considerably checked, if overseers of roads were to be sworn in open court, before one of the judges of the assizes.”

Maps

Before the publication of Ordnance Survey maps of Ireland in the early 1830s, grand juries had been the driving force in mapping Ireland. In 1774, grand juries had been given the power to raise a tax specifically to fund surveying their county and printing the resulting maps.

From 1784, grand juries were required to have their county map prominently and publicly displayed during the assizes, and soon began to compete with each other in the quality of their surveys and magnificence and size of their maps.

The first Ordnance Survey maps of Ireland were published in the early 1830s, and Co Armagh was one of the earliest of these. The first six-inch-to-a-mile sheet that covers Poyntzpass has the following footnote:

Surveyed in 1835, by Lieutenants Bordes, Tucker & Bennett RE, and engraved in 1835, under the direction of Lieutenant Larcom RE.

Next: Corruption

- Wikipedia contains a good account of the Irish road system prior to this time. ↩︎

- The Oxford English Dictionary definition of presentment is “a formal presentation of information to a court, especially by a sworn jury regarding an offence or other matter”.

↩︎