The world’s first public, steam-locomotive-hauled railway, the Stockton & Darlington, was inaugurated in 1825. The first recognisably modern inter-city railway, the Liverpool & Manchester, opened in 1830.

On 4th April 1844, one hundred and one years after the Newry Canal opened, the prospectus for the Dublin & Belfast Junction Railway (D&BJR) was published. The full formal title of the railway was “The Dublin And Belfast Junction Railway, With A Branch From Drogheda To Kells”.

It proposed to link the Ulster Railway (Belfast-Portadown) to the Dublin & Drogheda Railway – a total distance of 56 miles – and thereby provide an unbroken rail route between Amiens Street in Dublin and Great Victoria Street in Belfast. The cost of construction was estimated at £12,000 per mile. The predicted time to travel between Belfast and Dublin was 3 hours and 30 minutes.

It would use a gauge of 5ft 3in rather than the more common English gauge of 4ft 8½ in; this wider track width would become known as the Irish Gauge. The proposed authorised capital was £950,000; Sir John MacNeill (then just Dr MacNeill) was appointed as Engineer to the company, the same post that Isambard Kingdom Brunel held for the Great Western Railway in England.

So, it is interesting that Alexander Richmond’s 1831 map of the Close Estate includes a very accurate indication of the route (the long broad curve above the canal) of the future railway through Poyntzpass. This was probably added once the railway company’s detailed plans were known, in about 1845, to show the impact on tenants’ holdings.

At the end of November 1844, adverts announced that “… copies of such Plans and Sections, together with Books of Reference” would be deposited with the local postmaster at each of the centres of population along the route, including Poyntzpass, presumably for public consultation, no later than 31st December.

Because they would have to be built across private land, every new railway first required its own individual Act of Parliament. The Act authorising the D&BJR received Royal Assent on 21st July 1845.

For construction purposes, the route was divided into sections; each was about eight miles long, and tended for individually. On 4th November 1845, the Newry Telegraph carried an advertisement calling for tenders for the fifth section of the railway between Goragh and Monclone via Poyntzpass. This was only a few weeks after the widespread realisation that a new disease might wipe out the potato crop, and the spectre of famine was starting to loom large.

On 10th May 1847 an ‘inquisition’ commenced at Poyntzpass, before a jury, to examine and settle competing claims for the compensation for land and property that the railway company needed to compulsorily purchase. 45 cases were scheduled to be heard, but all but five were settled privately before the inquisition began. It lasted six days.

Dargan Builds The Poyntzpass Section

William Dargan1 won the contract to build this section; in fact, he won the contracts for all the sections between Mullaglass and Portadown. At the peak of construction, it is estimated that he had 8,000 men building the D&BJR – and this was just one of his many projects! Labourers were paid 12 shillings a week, and skilled men such as masons could earn up to 24 shillings a week.

According to Joe Mackle2 who was the third generation of his family to work on the railway, and whose grandfather actually laid some of the original track in the 1840s, the first part of the local section was begun where the railway route came very close to the canal, near Lough Shark.

A small section of track was built, and a steam locomotive was brought up the canal in parts and reassembled there. It then carried materials both north and south to extend the track, moving sleepers and rails, as well as spoil excavated from cuttings to build embankments, and other materials.

James Bennet tells the same tale in his ‘diary’ and records that the name of the engine was ‘Rose’.

A Track Built Across A Bog

Remember that the railway is closely following the route of the Newry Canal – and that was built through the old Glann Bog! So, before the track bed could be laid, huge quantities of osier bundles, imported from England and again transported up the canal, had to be laid across the boggy sections to provide a solid foundation.

This was an age-old technique; brushwood bundles provided firm foundations for most of the Russian city of St. Petersburg, built by Peter The Great.

The technique was later used in the construction of the Liverpool to Manchester railway across Chat Moss and the West Highland Railway across Rannoch Moor in Scotland. Once they were buried in the bog, the anaerobic conditions meant that the osiers did not decay.

Goraghwood Provides The Stone

Stone for the Craigmore Viaduct, the Egyptian Arch at Bessbrook and for track-bed ballast came from the new quarry at Goraghwood, adjacent to the track.

Dargan had his own steam engines, such as the ‘Rose’, which he used for constructing sections of railway. On the completion of a contract, he would often sell them in situ to the railway operating company, something that suited both parties.

Investor Cashflow Problems

The initial railway mania in Ireland was followed by a lull in the later 1840s because of the Great Famine. With many tenants unable to pay their rent, many big landowners (often investors in railway schemes) had severe cash-flow problems. Some were unable to make their obligatory stage payments, and much construction work ground to a halt for lack of cash.

In February 1848, the Newry Telegraph reported that the recent half-yearly Ordinary General Meeting, had voted to reduce the number of directors from sixteen to eleven, and to reduce each director’s pay from £1,300 to £900. The annual directors’ pay bill was slashed by over 50%, and £10,900 a year saved.

On 11 January 1850, Freemans Journal reported that the railway company had been granted a government loan to £300,000, to enable it to complete construction of the line.

In 1851, money was still tight. Thom’s Directory of Ireland reported:

“A large proportion of these calls3are unpaid, the arrears now amounting to upwards of £170,000. The directors are unwilling to advise the forfeiture of the shares until they can be disposed of without that loss to the company which the present market value of them would entail. Repeated but ineffectual applications have been made to government for military assistance, and the directors are now to compelled to rely upon private loans for the aid necessary to prosecute the undertaking.”

It’s Open!

The section of the D&BJR which runs through Poyntzpass was the very last to be completed. Early in 1851, directors and shareholders, principal contractor William Dargan, Chief Engineer Sir John Macneill, and various local dignitaries took part in an inaugural run.

At precisely 2.28 pm on 5th January, a train consisting of three first-class carriages left Mullaglass station and reached Poyntzpass a mere sixteen minutes later; the whole trip to Portadown took just 40 minutes. The return journey was even faster, with Freeman’s Journal reporting that “…the train reached 50mph at times!”

It is unlikely that, before that day, any of the passengers would have travelled at even half that speed – it was a new age of high-speed travel! The novelty was akin to a 1950s airline passenger travelling in a jet-powered plane for the first time.

The Mullaglass-Portadown section of the line opened for scheduled services the following morning, and the first train left Mullaglass at 8.45 am on 6th January 1851.

However, the railway would not become fully operational for direct Belfast-Dublin traffic until the Boyne Viaduct was completed, more than three years later. But north of the Boyne, there was now a continuous route all the way to Belfast, and revenue was needed immediately.

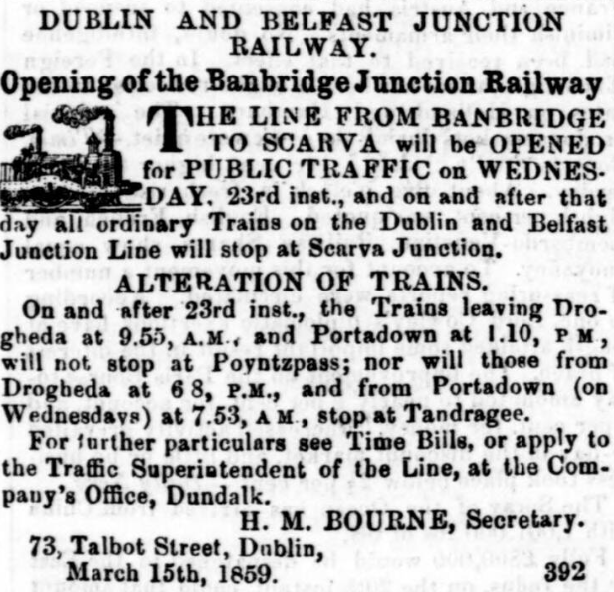

The Scarva-Banbridge Branch

This short branch line opened on 23rd March 1859. However, this seemed to coincide with fewer trains now stopping at Poyntzpass and Tandragee. Presumably, with the Banbridge branch now open, it was more beneficial to the railway and its revenues to stop at Scarva instead. Interesting that what we would call timetables were referred to as Time Bills.

Poyntzpass Station

On 15th December 1851, the Belfast News-Letter reported:

“The Dublin & Belfast Junction Railway Company are erecting a new station at Poyntzpass. Tenders are being received for the execution of the works”.

The Final Link

The Boyne viaduct – the final link in the chain – was not finally completed until 1855, at a cost of £124,000, and having bankrupted its original contractor. On 5th April, the first train crossed it without ceremony and there was now a fully open, continuous railway route from Dublin to Belfast. The trains stopped frequently and a typical journey between Dublin and Belfast took 3½ to 4 hours. Today’s Enterprise service takes 2h 10m.

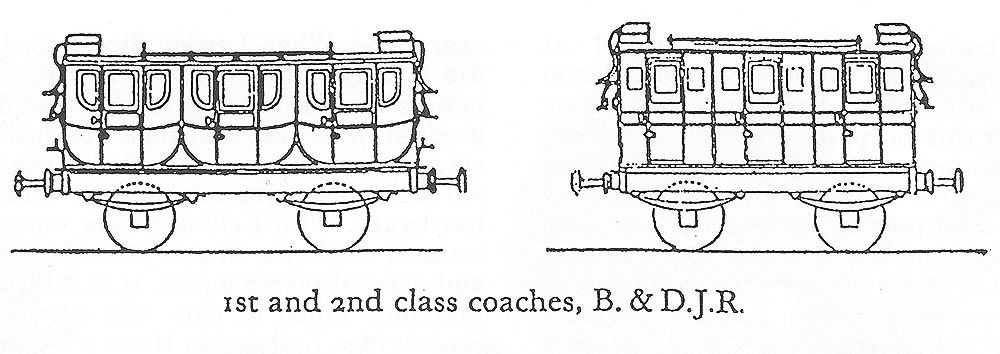

Rolling Stock

The construction of the early coaches is very interesting. As well as being very short by today’s standards, notice how closely the 1st Class carriage resembles three horse-drawn coach cabs stuck together; they would have seemed very familiar to the railway’s better-off passengers! Both types of carriage also carried luggage on the roof, open to the elements – again, just like horse-drawn coaches.

3rd Class coaches were just open wagons with seats, and had no roofs, so both passengers and luggage were completely exposed to the elements. As the train could reach 50mph, travelling 3rd Class during rain or snow must have been extremely unpleasant.

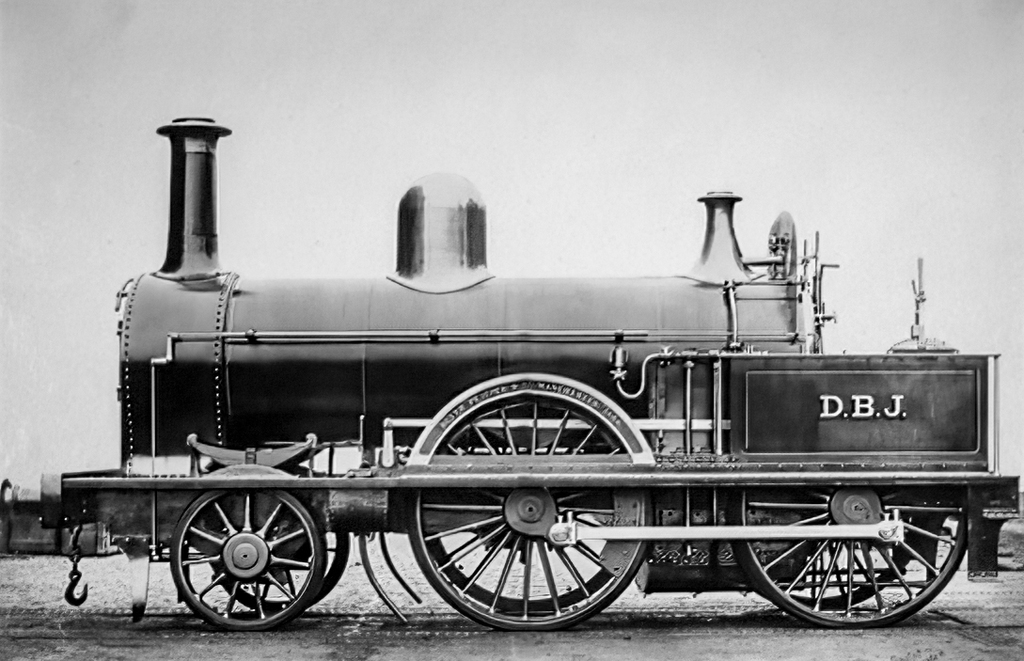

The website steamindex.com lists the locomotives built specifically for the DBJ. All of them were either built by Sharp, Stewart & Co, or by Beyer Peacock & Co, both based in Manchester. The locomotive shown above, a 2-4-0 configuration, appears to be either number 18 or 19, built by Beyer Peacock in 1866.

Some features are worth remarking on:

- The almost total lack of any weather protection for the footplate crew, other than the two forward-looking glass windows which were obviously needed for safety.

- The large dome above the centre of the boiler was called the steam dome. Steam needed to be as dry as possible to prevent damage to the drive cylinders, and this is where the driest steam accumulated and was drawn from.

- What appears to be a second small chimney near the footplate is for venting excess steam

- The vertical metal bar just in front of the front wheels is called a ‘life saver’ and its purpose was to remove debris that had accidentally or deliberately ended up on the track, and prevent derailment. It was our modest equivalent of the American ‘cow catcher’.

- The ash tray underneath the firebox, visible between the drive wheels.

- There is not yet a steam coupling hose for brakes on the rest of the train.

Investors Need Quick Returns

The D&BJR opened as a single-track railway; this was very sensible as it could start generating revenue as soon as possible for the least possible cost, and reduce cash flow demands on the shareholders.

However, it was always planned that a second track would be added to allow full two-way working along the whole route; all the track beds, bridges and tunnels were built wide enough to allow this. The initial financial success of the railway allowed this to be done earlier than originally planned, and the additional tracks were laid between 1858 and 1862.

Inpressing The Press

The Newry Telegraph of 7th July 1859 carried a very lyrical account of an excursion from Dundalk to Belfast.

“On Saturday last the Directors of the Dublin and Belfast Junction Railway gave a pleasure excursion to Belfast…and, after getting a number of carriages attached, started off with its living freight towards the Athens of Ireland. Passing through…we entered on the wild scenery of Meigh, relived now and then by a glance of the handsome residences of Messrs. Foxall4 and Chambre, with their strangely planted demesnes, said to represent the great struggle on the field of Waterloo, with the stations occupied by the French and Allied armies.

On went the hissing engine, passing the historic town of Newy…on through old Goragh, the Ulster Canal5with its cool waters, with now and then a solitary lighter (not the bustling scenes of the days of Dargan) relieving the eye; through Poyntzpass, with its neat church ornamented with flags; Tandragee with its Ducal castle, to Madden Bridge Junction…”

This was probably a ‘boondoddle’ for journalists, designed to generate widespread positive press coverage for the still-new railway, and encourage leisure travel.

Poyntzpass Station Opens

Poyntzpass station opened on 6th January 1862 – over 10 years after tenders for its construction were invited!

Nearby, work on the Lissummon Tunnel6, one mile minus one yard long, was completed in February 1864, allowing the Newry & Armagh Railway to finally open.

How Fast Were The Trains?

I’ve not yet discovered any timetables from the time when the D&BJR became fully operational between Belfast and Dublin.

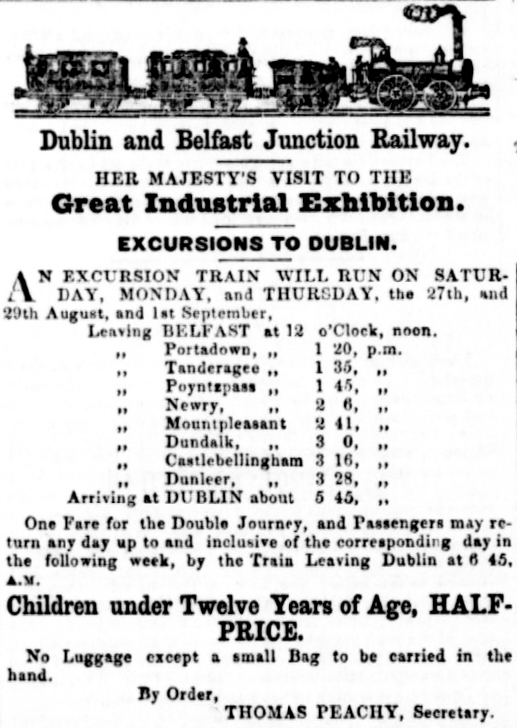

However, this advert from 1853 gives some indication. Admittedly it is a slow train, calling at many stops, the entire journey took just under six hours! With the total distance being approximately 112 miles, the average speed was just under 20mph!

Notice that only one small piece of hand luggage per person was permitted, reminiscent of today’s budget airlines!

The design of locomotive shown in the graphic at the top of the advert is also interesting – the entirely open driver’s position with just some rails preventing him from falling off, the very high main chimney, the small secondary chimney in front of the driver, the very small steam dome, and the fact that the locomotive has just four large drive wheels.

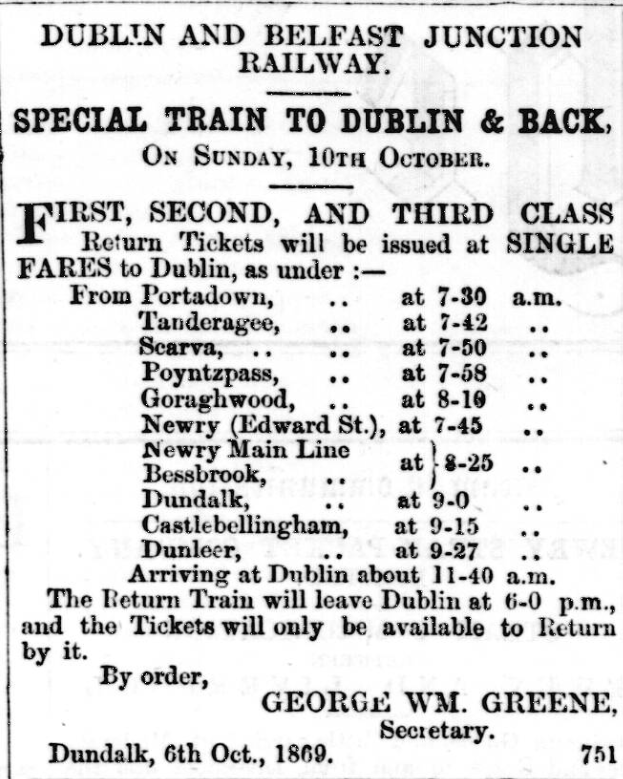

16 years later, another newspaper advert promoted a special trip to Dublin on the same basis – a return trip for the price of a single.

Again, it is interesting to look at the travel times; leaving Portadown at 7.30am, you did not arrive at Dublin until ‘about’ 11.40am, over four hours later. The Portadown to Dublin distance is 87 miles, so the average speed was still only 21mph.

And assuming that the return journey took the same time, during your half-price Sunday jaunt from Portadown, you would have spent almost eight-and-a-half hours on the train – just a few minutes less than the scheduled flight time from Miami airport to London Heathrow!

The scheduled time for the Dublin-Belfast journey on today’s Enterprise express service is just one hour and forty minutes, an average speed of 67mph.

Consolidation

In 1875, the D&BJR merged with the Dublin & Drogheda railway to form the Northern Railway of Ireland, which in turn merged with three other railways just a year later to form the Great Northern Railway of Ireland (GNR), which remained its identity until joint nationalisation and final liquidation in 1958.

On 19th July 1889, The Witness newspaper reported:

“…the directors of the Great Northern Railway have presented a gratuity of £50 to the signalman William Dodds, who, on Saturday morning last, switched the runaway wagons which broke loose from the luggage train opposite the Wellington cutting on the down line near Poyntzpass a few minutes before the mail train from Belfast came up, and thus averted a fearful catastrophe. The directors have also increased Dodds’ wages by 2s a week.”

The GNR prospered; the railways now ruled the world of rapid ground transport, and in February 1907, the directors of the GNR, at their half-yearly meeting in Dublin, announced annual revenues of over £1 million, and declared “…the usual dividend of 6¼ percent.”

Disruption

The early 1900s was a very active period for local MPs asking Poyntzpass-related questions in Parliament – and the level crossing featured regularly. There were regular complaints about how tardy the GNR was in opening the gates, and that traffic was often held up for up to 20 minutes while shunting operations were carried out. A footbridge was requested, but never provided.

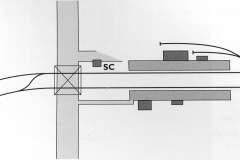

You can see from the track diagram in the gallery below that one pair of points was just south of the level crossing, while the other was beyond the north end of the platforms. Presumably it was designed that way so that when the engine had to change which end of the train it was attached to, all of the carriages could be left ‘parked’ at the platform.

Arson

On 7th July 1921, Poyntzpass signal box and its equipment were destroyed by arson, and the GNR lodged a compensation claim for £2,500. It is possible that the attack was carried out by local Republicans emulating attacks on seven railway signal boxes in London by Sinn Fein three weeks earlier.

Travelling To School In The 1950s and 1960s

Many of those who grew up in the village in the 1950s and 1960s have fond memories of going to school in Newry or Portadown by train, first by steam train and later by diesel railcar. The single-carriage railcar service between Scarva and Newry was inaugurated as early as 1934.

The railcar that left Poyntzpass for Newry at about 8am would make a couple of stops to pick up schoolchildren from the trackside where a minor country road crossed the track but there was no nearby station. One such informal stop was about ¾ mile north of Jerrettspass. When the train stopped, a set of wooden steps was placed against the side of the carriage, underneath a carriage door, by someone at the trackside, and the guard would let the kids on or off the train.

Specials!

‘Specials’ – one-off trains not on the normal timetable – were also a regular feature. In January 1951, local papers carried adverts for cheap day-return tickets to Belfast to see the pantomime at the Grand Opera House, or the circus at The King’s Hall, Balmoral; your local stationmaster could even get theatre tickets for you!

On 15th April 1940, the GNR advertised cheap day return railway tickets from Belfast to the Newry Harriers’ point-to-point races at Taylorstown. A third-class ticket cost three shillings (15p)!

In the ‘50s and ‘60s, the annual local Protestant churches Sunday-school summer day-trip to Bangor was a big event; in the morning the down7 platform would be packed with parents (mostly mothers) and excited children, as an extra-long steam train pulled into the station. Many mothers then spent the journey removing grit from the smoke from tender young eyeballs!

The Steam Injector

For me, one of the most wonderful aspects of the steam locomotive is a clever little device which the driver uses to top up the boiler with water periodically. It has no moving parts, and is called a steam injector. It solves the problem of how to move cold water at atmospheric pressure into the boiler which is at many times that pressure. On of the great skills of a steam train driver is when, and for how long, to use the steam injector.

Click on the link above to watch an explanation, and wonder at human ingenuity 🙂

Notes On Signals And Lamps

I posted some questions about signal lamps and oil online; Nigel Murphy and Ian Stewart replied:

“Long burning lamps became available in the early 1900s which would burn for 8 days, but in general were serviced every 7 days. Before that lamps had to be serviced daily and some railways had them extinguished during the day and re-lit at night. There is a specific distillation used: “Signal Lamp Oil”8 not just any old paraffin, as it will not last 8 days and will smoke heavily and obscure the lens. There was also a larger 9 day lamp which was used in far away signals. In stormy weather it might not get changed for 9 days…

“As well as refilling the lamp burners, the lamp man should clean the inside and outside of the lamp lens and the coloured spectacle glasses on the signal arm. The wick of the burner should be trimmed (cut off) and the wick extended to the correct height- or replaced if insufficiently long.

“Lamp burners were generally serviced in this way at a lamp store, where all the materials were kept under lock and key. Then the lamp man would take them to the signals and swap them over (rather than service them on site). Officially lamp oil was kept in the hut only but I would imagine some “emergency “ supplies were stashed in suitable locations, particularly if the lamp man was off duty and a lamp blew out, when the signalman had to go and replace it.”

- The advent of the railway was generally welcomed in Poyntzpass; at the October 1850 meeting of the D&AFS, one of the many toasts was “Mr Dargan and the Railway Company.” ↩︎

- See “Walking The Line” by Joe Mackle, BIF Vol 6, 1993 ↩︎

- When investors bought shares in a railway company, they did not provide all of the necessary capital ‘up front’. However, their shares legally obliged them to make further payments on certain dates, so the shares were both an asset and a liability. ↩︎

- Currently the Killeavy Castle Hotel. ↩︎

- This was, of course, the Newry Canal, not the Ulster Canal. ↩︎

- See “The Newry And Armagh Railway And Lissummon Tunnel” by John Campbell, BIF Vol 2, 1988 ↩︎

- Mickey Sands explained the naming of the tracks to me – “You always go UP to the capital” which of course was Dublin when the line was first built. ↩︎

- A consistent yellow flame colour was also vital for the colour the signal; for example, the lens glass in the green (“OK to proceed”) signal was actually blue! … but the yellow flame seen through the blue lens showed as green. ↩︎