From soon after the Plantation era, almost the whole of Ireland was in the hands of a very few, often absentee, mainly Anglo-Irish landlords1. Estates of 5,000-10,000 acres and upwards were common. Farmers who owned the land they cultivated were almost unknown; almost all were tenants.

Some landlords, like John Moore of Drumbanagher, and his successors the Close family, were well liked, and dealt fairly and sympathetically with their tenants. Others, especially absentee landlords in the poorer western parts of Ireland, were ruthless and brutal.

Volumes have been written about the land reform movement in Ireland in the 19th century. We shall concentrate on examining how the ownership of the land was transferred from the local elites into the hands of the many small farmers in our area.

The First Cracks Appear

As mentioned earlier, the poor harvests of 1816-17 and especially the Great Famine of the late 1840s, were seismic events which initiated the slow process of breaking up the big estates.

Encumbered Estates

In 1848-49, Parliament passed two Encumbered Estates Acts, to facilitate the sale of often highly mortgaged estates which had been bankrupted by tenants being unable to pay rents during the famine years. Under these acts, a creditor could apply to have the debtor’s property sold to meet the debt “where the debts had risen above 50% of the yearly income”.

Sales of The Fiveys’ Estate

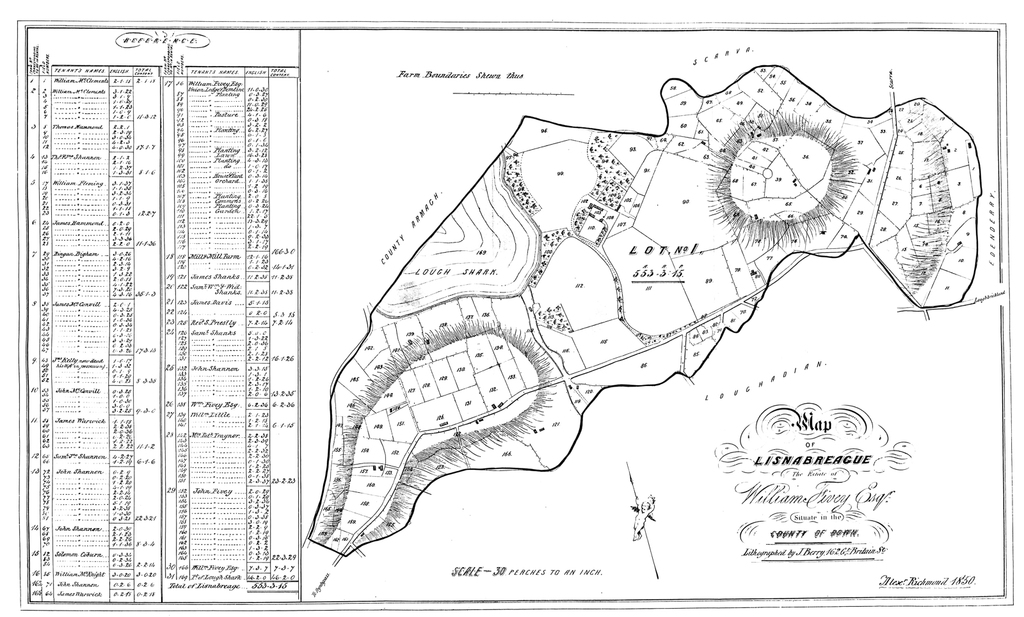

An early casualty was William Fivey of Lisnabrague Lodge (formerly Union Lodge). However, Fivey’s woes were more to do with gambling losses than unpaid rents. On 27th September 1851, the Commissioners For The Sale of Encumbered Estates advertised the sale of the Fivey Estate, by auction on 9th December.

The highly detailed prospectus for this sale, giving details of the acreage and tenant of every single field, townland by townland, and containing detailed accurately surveyed maps, was prepared by Alexander Richmond (who had similarly surveyed and mapped the Close estate in 1831) and his son David. The estate was offered in six separate lots.

Townlands As A Unit Of Sale

On 6th December 1852, the Commissioners For Encumbered Estates advertised that the townland of Loughadian, owned by the Fivey family, was to be sold by public auction. Perhaps the previous sale was only partially successful?

Townlands (originally called ballieboes) had been convenient units for the English Crown when making land grants during the Ulster plantations, so many of the large estates consisted of whole townlands. They continued to be convenient units when parts of an estate were being offered for sale; for example, when the trustees of the failed Newry bank sold John Moore’s Drumbanagher estate in 1817, it was offered in tranches consisting of one or more townlands.

And as we see above, this was still the practice in the 1850s. The implicit assumption was that purchasers were still going to be large, rich landowners, or perhaps the more successful members of the rising merchant class wanting to diversify. Land ownership was still beyond the means of most tenant farmers. However, selling off whole townlands was an early step towards fragmenting the large estates.

On 10th May 1853, a number of Fivey-owned townlands were sold by public auction at a sitting of the Encumbered Estates Court in Dublin. John Andrews bought Loughadian (541 acres, and obviously still unsold since 1851) for £12,660, equivalent to 20 years of its rents, and Lisnabrague (553 acres) was sold to ‘Mr Stewart’ for £13,300, equivalent to 14 years’ worth of rents.

Drumbanagher & Acton

As far as can be judged from newspaper reports, especially the annual dinners of the D&AFS, relationships between the Close family and their agents on the one side, and their tenants on the other, continued to be fairly smooth and mutually respectful. On 30th December 1880, the following appeared in the Newry Reporter:

“RENT NOTICE. Acton and Drumbanagher estates. Although the late harvest has been a most abundant one and your rents are extremely moderate, and have not been raised for half a century, Mr Close, sympathising with you and willing to share with you the losses you have sustained by the deficient harvests of 1877, ‘78, and ‘79, authorises me to continue for this year the abatement of £10 per cent, which he allowed last year to such tenants, holding at will2, as feel that they really require it.

As this abatement will necessarily reduce Mr Close’s income, without in any degree reducing the outgoings and charges which he has to pay, it really amounts to very much more than 10 per cent upon his actual income, he therefore confidentially relies upon its tenants increasing their exertions in the cultivation of their farms, so that his moderate rental may in future be freed from abatements, which press so severely upon his resources. £10 per cent upon the year’s rent up to November 1880, if paid before 1st of March. Five per cent upon the year’s rent up to Nov. 1880 if paid before 1st of May. These abatements allow only to holdings at will and will in no cases be allowed on payments made after the above dates. PETER QUINN. The Agency Office, 10th December 1880.”

However, this text is actually a quotation from a much longer letter from Eiver Magenis!

In it, this fierce Nationalist robustly attacks landlordism through an ironic Socratic-style dialogue, implying that Quinn’s letter is mere propaganda, as it only applies to ‘tenants at will’. And it wasn’t automatic; even if they qualified, they would have to approach the land agent and request it – a brave act as their tenancy was the most precarious sort, which a landlord could revoke without giving a reason. Little wonder, then, that on 20th October 1881, the Newry Reporter announced:

“On Saturday, a branch of the Land League will be formed at Poyntzpass. The organisers are announced to attend, and a placard asking for support has been extensively posted in the district”.

However, it later reported that:

“The meeting…did not come off, in consequence of the Government Proclamation on Thursday declaring the organisation illegal and criminal.”

British Government Financial Support For Reform

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Conservative government in Westminster initiated a policy designed to kill demands for Irish home rule demands by kindness, through introducing constructive reforms in Ireland. The first major step towards resolving the land question was the Purchase of Land (Ireland) Act of 1885 (the Ashbourne Act). It established a £5 million fund from which tenants could borrow the money to purchase their land and pay it back over 48 years at 4% interest. Another £5 million was added in 1889.

The other side of the landlord-tenant equation was addressed in the 1903 Land Purchase (Ireland) Act (the Wyndham Act) which provided for government financial inducements to the owners to sell their estates. So by the early 1900s, the Government was financially assisting farmers to buy out their tenancies, and compensating landlords who were prepared to sell them.

Loughadian Sold To Tenants

In 1896, some 40 years after John Andrews bought Loughadian, the tenants were not at all happy with his successors. On 15th January they met at Searight’s Railway Hotel, and resolved to ask Thomas J. Andrews3, the current landlord, for a 30% rent reduction. They protested that Andrews’ rents were twice those of nearby equivalent farms, and that the price of flax had dropped by over 80% in the previous two decades.

Discussions with the Andrews family quickly progressed from a possible rent reduction into proposals for the tenants to buy their farms outright. On 3rd November the following year, the tenants met with Andrews and his agent “in Mrs Griffiths’, Poyntzpass” and agreed to purchase their holdings for 17½ times their annual rent.

A few weeks after this, on 23rd November, the tenants met once more, this time at the home of Mr M Canavan4 and presented him with a gold watch and chain, to thank him for his assistance in negotiating terms for the purchase of their farms. The formal public notice that Andrews proposed to sell Loughadian and that the terms had been registered under the Land Purchase Act appeared in newspapers four months later.

Drumbanagher & Acton Sold To Tenants

On 19th October 1903, a meeting of Close’s tenants was held in Poyntzpass, to discuss terms for purchasing their farms. Col Close had already agreed in principle to selling his estate if acceptable terms could be agreed. The meeting discussed proposals for valuing the farms in terms of multiples of their annual rents.

Step forward Heber Magenis, prominent local citizen, farmer, auctioneer and valuer, and passionate advocate of land reform, who first addressed the meeting and who was then, along with R N Savage, asked to negotiate final terms on behalf of the farmers.

While the negotiations were under way, the terms proposed by both sides were prominently reported on in the press and are documented in detail in Joe Canning’s BIF article mentioned earlier. Although Col Close was very amenable during negotiations, his agent, Henry S Close, appears to have been untypical of the long tradition of well-liked Drumbanagher agents, and was reported as describing one meeting as “cock and bull”.

The final terms were overwhelmingly endorsed by tenants; 250 accepted, and only five – a mere 2% – were against. The final total price paid by the tenants to the Close family was £52,423. However, we don’t know how much the Close family received in inducements to sell from the 1903 Wyndham Act funds.

Some landlords embraced the act enthusiastically. Side-by-side with the newspaper report on the initial Drumbanagher negotiations was another stating that the owners of the Verner estate were encouraging their tenants in Moy to put forward proposals and reminding them that other Verner tenants in Co Tyrone had purchased at the time of the original 1885 act.

In May 1904, the Dublin Gazette reported that “… Major Maxwell Close, claiming as tenant for life of lands known as the Brootally Estate and the Dugarry Estate, County Armagh, is proceeding to sell to their tenants under the provision of the Wyndham Land Act.”5

Maxwell Close’s Brootally Estate

Maxwell Close also owned the Brootally Estate just southwest of Armagh, consisting of 3,250 acres. He sold it to his tenants in the early 1900s for £52,423. However, he actually leased it from Trinity College Dublin, and a complex court case was heard in 1905 to determine what the loss of the college’s perpetual rents should be valued at, and therefore how much of the final sum was due to them. The outcome was … the great majority of it. Close was left with just under £7,500 from the sale, before legal costs were deducted.

The Swifte Estate

The Swifte estate was owned by Ernest Godwin Swifte (1839-1927) (pictured right) of Dublin, a barrister and KC, later knighted, and nephew of Lord Carlingford. His father appears to have been the literary executor of Jonathan Swift.

The Portadown news, describing his appointment as a Dublin divisional magistrate in June 1890, stated “Mr Swifte is well known in Portadown, being the owner of a large estate in the neighbourhood.”

In an advert in the Portadown News in December 1892, he made a rent abatement offer to his “judicial tenants in Ballyworkan, Drumnakelly and Aughantaraghan” (these may not have been all of his townlands).

In the autumn of 1903, negotiations were under way, as they were on the Close estate, for the tenants to purchase their holdings. A meeting was held in Poyntzpass, chaired by R J Monaghan, in which Swifte proposed purchase terms, and his tenants made a counter proposal.

On 28th June 1907, the former tenants of both the Close and Swifte estates held a joint meeting in Jerrettspass to honour Henry Reside, who had managed the negotiations on behalf of the estates. He was praised for his fair dealing during the period and was presented with “a beautifully illuminated address and a handsome roll-top desk, which was supplied by that well-known Poyntzpass firm – Allen Brothers.” Heber Magenis had represented the Close tenants, and Charles Loy the Swifte tenants.

Dr MacDermott Advocates Industrial Farming

Dr MacDermott, writing as APA O’Gara in ‘The Green Republic’ in 1902, was opposed to both the old system of landlordism and the new system of owner-occupier framers. The novel was published at the height of the period of Irish land reform and the fragmentation of the old estates.

He believed that the new normal would be just as disastrous as the old one had been, and that the land could never produce to its full potential until farming was treated as an industry, with the land owned by large companies, ruthlessly applying scientific principles, and employing the most modern of machinery to maximise crop production at the expense of grazing.

Today we call it ‘agribusiness’.

- See the very comprehensive article “Landlords And Tenants in Co Armagh” by Joe Canning, BIF Vol 2, 1989. ↩︎

- A very insecure form of tenancy where tenancies were only renewed from year to year, at the whim of the landlord, rather than for a set number of years or ‘lives’, and there may not even have been a written tenancy agreement. ↩︎

- Eighteen years earlier (May 1878) the Loughadian tenants wrote to the Northern Whig praising the Andrews family and the way that they treated their tenants, and in particular how they applied the Ulster Custom to tenants of land they purchased in other parts of Ireland. But people may have many motives for what they write – and did they write of their own free will? ↩︎

- Bassett (1888) lists Michael Canavan, as a ‘spirit grocer’—a grocer who was also licensed to sell alcohol. This is almost certainly Michael Canavan (1857-1932) of Railway Street, who was also a cattle dealer and butcher; we mentioned him earlier in connection with the street drains saga. As a prominent nationalist, he was heavily involved in the formation of the Poyntzpass branch of the United Irish League. ↩︎

- Were these the lands that resulted in the court case when Trinity College Dublin claimed that they were due over £50,000 from the sale of Close lands? ↩︎