Maxwell Close (1783-1867)

… was born at the Close ancestral home, Elm Park, near Armagh, the eldest son of the Rev. Samuel and Deborah Close.

In 1800, aged 17, he joined the army and later served in the 20th Regiment. He served in the Napoleonic Wars and retired from the army in 1815.

His first appointment as one of the High Sheriffs of Co Armagh was for the year 1818.

His wedding at Bath in March 1820 to Anna Brownlow, daughter of Lord Lurgan, was widely reported in newspapers throughout the British Isles. They appear to have remained living at Elm Park for many years before eventually moving to Drumbanagher.

Buys The Acton estate

Sometime between May and November (the two months on which rents were payable by tenants) in 1817 the then Major (later Colonel) Close purchased the Acton Estate from William Hanna Jr. He was aged about 34 at the time.

An inscription on the back of the portrait of Alexander Stewart of Acton in Armagh Museum asserts that Close paid almost £100,000 for the estate – a huge sum at the time.

In modern measure, the estate was 5,432 acres (22 km2 or 8.5 miles2).

Buys The Drumbanagher Estate

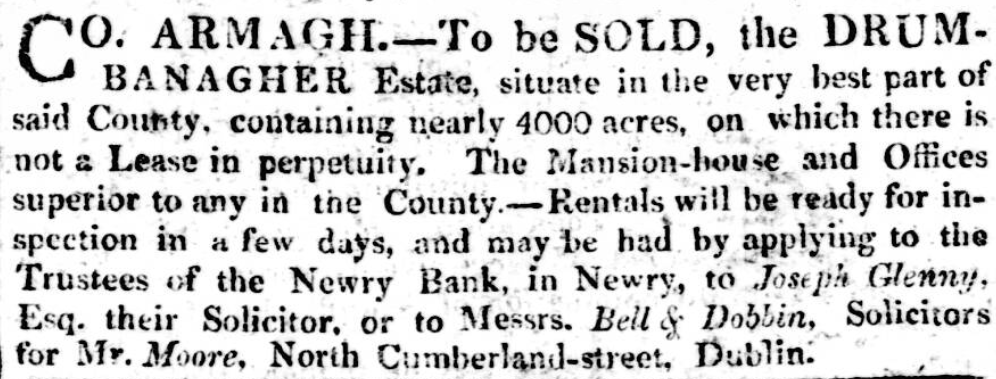

On 8th July 1817, the the Trustees of the failed Newry Bank placed an initial advert in the Dublin Evening Post that John Moore’s Manor of Drumbanagher (4,000 acres1 – 1600ha, 16 sq. km, 6.25 sq. miles) would be coming up for sale.

On 4th October 1817, they publicised in much more detail how the sale would take place.

“Sealed proposals will be received by Bell and Dobbin, until the 12th day of December next, on which day they will attend at the Commercial Coffee-Room, Dublin, at the hour of 2:00 o’clock in the afternoon, with said proposals, and also with a sealed paper, when the several proposals will be opened, in presence of such persons as may attend; and the person making the highest proposal above the sum specified in the sealed paper, will be declared the purchaser, and must sign a memorandum, to be prepared for the purpose.

“A sum of Five Thousand Pounds will immediately be required as a deposit, and a further sum of Seventy-Five Thousand Pounds must be paid within one month after being declared the purchaser, or the deposit forfeited; and interest to be computed on the entire, from the first day of November proceeding from which period the Purchaser will be entitled to the rents; and it is expected that the residue of the purchase money will be allowed to remain a charge upon the estate,”

Just six weeks later, another advertisement announced that the Drumbanagher estate would be “Sold by public auction (instead of the mode proposed in the former Advertisement) at the Commercial Buildings, Dublin, on the 12th day of December”. All of the other conditions remained the same.

Details of the sale were widely promoted; the advert also said:

“Particular Rentals are posted in the principal Coffee-Rooms in Dublin and London; and also in principal towns throughout Ireland.”

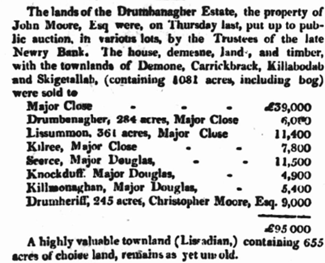

However, it seems that the December auction did not take place either, or that bids for the whole estate were not forthcoming or were too low. The report opposite from 22nd April 1818 implies that the estate was then offered for sale at auction in smaller units (townlands or groups of townlands) four months later.

It can also be seen that Major Close did not buy the whole of Moore’s former estate. Three of the southernmost townlands, adjacent to Jerrettspass, were bought by the Douglas or Dowglass2 family from near Crumlin.

In modern measure, the estate was 2,547 acres (10.3 km2 or 4 miles2).

The combined estates of Acton and Drumbanagher covered almost exactly 8,000 acres (32.3 km2 or 12.5 miles2). As they shared a long common boundary, they could effectively be run as single estate.

In September 1820 the townlands of Drumheriff (bought earlier by Christopher Moore) and Lisadian (unsold) were once more advertised as being for sale at auction, in the Dublin Evening Post3.

The Year Without A Summer

1816 was the famous “Year without a summer” when there was worldwide climatic disruption due, it was realised years later, to the huge emissions from the eruption of the Mount Tambora volcano in Indonesia.

Two extremely wet years4 resulted in very poor crops and much hardship among Irish farmers. As a result, many were unable to pay the rents due to the large landowners, whose cash flow was therefore drastically reduced; many landlords were unable to meet the payments due on the large mortgages that they had taken out with their estates as collateral. In effect they became bankrupt.

The lingering effects of this disastrous summer may well have reduced the selling price of the Drumbanagher estate lands.

A similar but even more severe crisis, for tenants and landlords alike, was triggered by the years of the Great Famine in the latter 1840s, which led to the Encumbered Estates Acts.

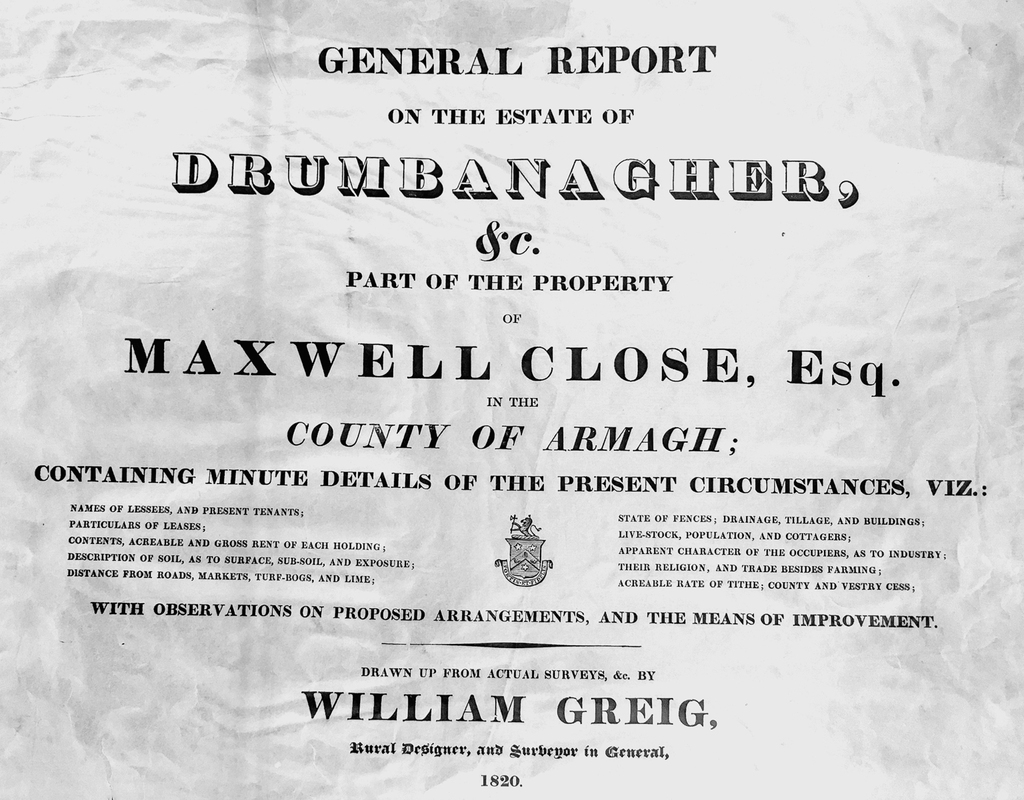

Greig’s 1820 Survey

When Maxwell Close bought the adjacent estates of Drumbanagher and Acton, he wasted no time in starting to improve them.

One of his first acts was to appoint William Greig of Belfast to carry out an immensely detailed survey and audit of the Drumbanagher estate and make recommendations on how it could be improved. Drumbanagher was his priority as Acton had clearly been better run and was more productive.

Greig was a Scot who came to Ireland in 1808 after four years’ experience as a ‘road engineer’, and from then until 1816 was mainly employed as a road surveyor by grand juries and Irish Postmasters General. He styled himself a ‘rural designer and surveyor in general’. He was commissioned to survey Lord Gosford’s estate at Markethill about 1817, and produced an enormously detailed report which was not finished until 1821.5

Grieg Misunderstands His Gosford Brief

However, he seems to have greatly exceeded his brief, and utterly misunderstood why it had been commissioned. Greig quite reasonably thought that The Earl of Gosford wanted to improve his holdings in the way that Maxwell Close later did. However, it appears that his lordship’s main interest was simply to value the estate, so that he could raise mortgage finance for his pet vanity project – the building of the faux-Gothic Gosford Castle!

Greig’s Gosford recommendations were never implemented; in the words of one commentator, they were “like a large stone that sank almost without trace in the pond of Gosford estate management”. However, that management was at the time in the hands of Close’s cousin William Blacker, who we shall meet later and who probably recommended Greig to Close, having seen and approved of his work at Gosford, albeit misguided!

For all the goodwill that had existed between Sir John Moore and his Drumbanagher tenants, his tenure seems not to have been of great benefit to either. Greig6 paints a gloomy picture of bad harvests, mismanagement, poor farming practices and impoverished tenants.

Greig recorded an extraordinary amount of detail about each tenant, and it is worth listing these in full.

- Townland.

- Name of the lessee and of the current tenant.

- Tenant’s number, for cross reference to the annual records of rents received.

- Lease number.

- When the lease was granted.

- Number of years or ‘lives’ granted.

- Specific conditions attached to the lease.

- Soil type, both surface and subsoil.

- Area covered by the lease (as determined previous and possibly new surveys).

- Rent per acre and total rent payable to the estate each year.

- Taxes payable, both tithe (parish) and cess (county).

- How far the tenant had to travel to get both lime and turf.

- How far it was to each of the nearest major markets – Newry, Tandragee and Banbridge.

- Nearby public roads – how far from the farm, how easy to get to, and where they led to.

- The overall state of repair of fences, drainage, and tillage.

- Buildings – how many houses, barns, byres, and stables were on the property, their state of repair and what their roofs were made from.

- Whether the tenant had any other trade, such as weaving.

- Looms – how many, and whether they were in use or not.

- Livestock – how many cows, other cattle, horses, sheep, and pigs.

- The ‘character’ of the tenant – from ‘indolent’ through to ‘industrious’

- The family’s religion.

- How many of each of men, wives, children, servants lived on the farm, and their ages and whether they have any other trades.

…and any other details and opinions on the farm and tenant that he thought worth recording!

He went on to make observations on many factors such as the surface and sub-surface geology of the estate, townland by townland, and the ease or difficulty of obtaining lime.

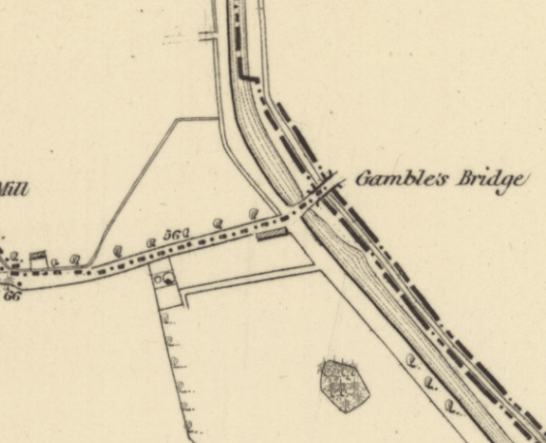

It is not mentioned as a specific recommendation in the report, but perhaps this is why the two lime kilns close to Gamble’s Bridge were built, so that the raw ingredients – coal and limestone – could be imported by canal and the lime produced right at the heart of the estate, making it easily accessible to every tenant. They were certainly in operation by the time of the OSMI (1835-38).

Grieg Is Not Impressed

Greig was critical of much of what he found, including:

- The state of farms in Ireland in general was much worse than in England and Scotland.

- Over the decades, as families had grown, holdings had been repeatedly sub-divided to provide at least some land for each adult male child. This had resulted in some becoming too small to support a family. Given the primitive and labour-intensive farming technology of the days, there was too little land to support a growing population other than in widespread poverty.

- Lime, manure, and good tillage were important to improve the land and make it more suitable for growing barley and other grain crops, not just oats.

- Many of the small farmers were ignorant of the principles of ‘modern’ agriculture and so the land was not producing to anything like its full potential.

- How badly off the estate was for turf bogs to cut for fuel, and the high cost of what local turf was available.

- How relatively poorly off7 the Drumbanagher estate tenants were compared to “the comfortable and opulent tenantry of the very superior Estate of Acton” mainly due to the system of tillage used on the estate being inferior to that of the Acton estate and in nearby Co Down.

- Landlords had steadily increased rents during the ‘good times’ of the Napoleonic wars but had not reduced them now that times were much tougher. As a result, tenants could not afford to improve their farm, to the detriment of both tenant and landlord.

His overall conclusion was that the estate had greatly declined under Moore, and that drastic action was needed. Of course, “You called me in just in the nick of time; urgent action is needed is to save the business” is often the conclusion of management consultants, but Greig was broadly correct.

What Must Be Done

He made many pages of detailed recommendations (in the very florid language of the time) for improving the estate. First, he set out what needed to happen:

- No further sub-division of holdings should be permitted, and the practice should be explicitly forbidden in all new or renewed leases, on pain of forfeiture.

- Small holdings should be combined into larger, more viable tenancies, but it would be ruinously expensive to try to make this happen immediately. It should be done gradually, with incentives offered to tenants, especially the larger and more successful ones.

- It was imperative to educate tenants in modern scientific farming principles, using a combination of carrot and stick.

- More efforts should be made to obtain public funds to create, repair and improve small local roads.

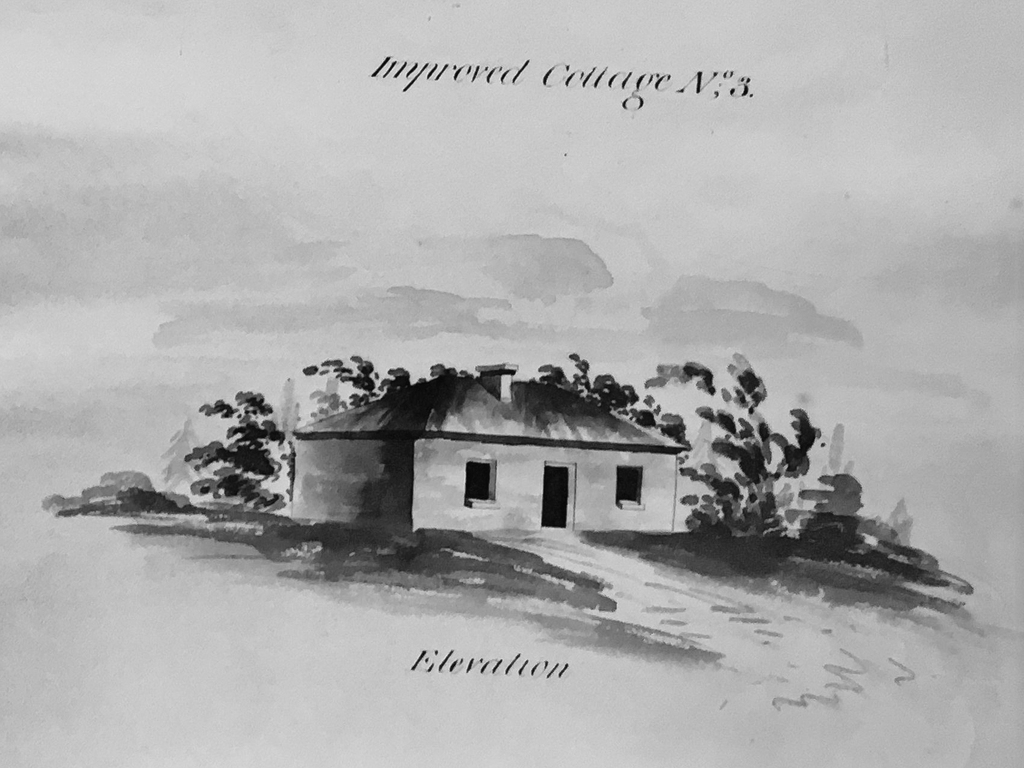

The report also included drawings and plans for several ‘ideal’ farmhouse cottages which tenants might build.

The Drumbanagher And Acton Farming Society

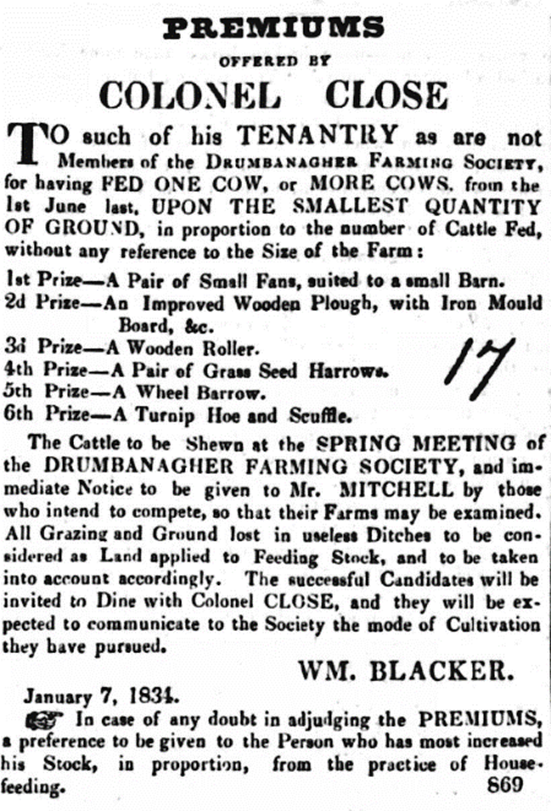

One of the main practical outcomes of Greig’s report was that Close helped found the Drumbanagher and Acton Farming Society (D&AFS) in 1820, with the primary aim of improving of farming methods.

Big landowners setting up agricultural societies was common across the British Isles in this era, as a way of teaching tenants the rudiments of agricultural improvements, through lectures, meetings and discussions, lease conditions, and offering inducements and prestige in the form of annual prizes, or premiums.

Greig recommended that prizes should be offered in three classes – above £20 annual rent, £10-£20 annual rent, and below £10 annual rent. He proposed awarding separate prizes in each class for better fences, better drains, liming, planting clover and grass, new buildings, tree planting, consolidating small farms and the neatest tenancies.

An annual show, with prizes, was instituted in 1821. Judges each year included Col Close, his land agent, and several of his most successful larger tenants, including Crozier Christy and Alexander Kinmonth. Prizes were offered across a wide range of different arable and livestock categories such as neat husbandry, green crops, carrots, vegetables, cottages, milch cows, two-year-old heifers, one-year-old heifers, weaning calves, bulls, brood sows, firkin of butter, lump butter, and best quality flax.

The judges toured the estate in the days before the show, assessing the crops and farm improvements, with awards being made on show day. A key feature of the prizes was that they directly contributed to the further improvement of the estate – barrels of lime, a new plough and so on. Close sought to create a virtuous circle and, through it, lift as many of his tenants as possible out of poverty.

For example, the Belfast News-Letter reported that at the D&AFS 12th annual meeting and ploughing match in March 1833, “Col Close has forgiven rent on fields where the tenants grow green crops to feed livestock”, and the winner for most livestock per acre fed on green crops, Crozier Christy, won 50 barrels of lime. Even 10th place won 15 barrels! The farming practices that Close promoted were closely aligned to those advocated by his first cousin and sometime land agent, William Blacker of Gosford.

The Gamble’s Bridge Lime Kilns

This raises the question of when the twin lime kilns near Gamble’s Bridge were built. The most likely date is during the 10 years centred on 1827 – well after Col Close received Greig’s report, and before the D&AFS meeting mentioned above, where lime was given away so freely.

Raw ingredients – coal and limestone – could be imported by canal and the lime produced right at the heart of the estate, making it easily accessible to every tenant. They were certainly in operation by the time of the OSMI (1835-38). Greig’s report said:

“The chief supply of lime is from Newry to which place it is brought by water carriage from Carlingford &c and is of course proportionally expensive – This is a circumstance unfavourable to a soil so naturally deficient in calcareous matter, and the subsoil so generally cold retentive as the argillaceous strata and soil of Drumbanagher but not-withstanding the expense many of the more opulent tenants are in the practice of employing considerable quantities of lime, but to the occupiers of small holdings who are not able to keep a horse or to pay carriage; it is rarely attainable, and this forms one reason for endeavouring to augment the size of farms and to prevent their subdivision into portions too small to enable the occupiers to keep a horse as has already been the case to a ruinous extent”

The first edition (1830s-1880s) of the OSI map shows them clearly, but they are not marked as lime kilns. There are two other features of note:

- There is clearly a wharf or simple unloading place for lighters carrying limestone and coal, the raw materials, on the west side of the canal, close to the kilns. The opposite banks has been cut into to widen the canal at this point, to allow other lighters to pass easily.

- There is a private road or track, just over 100m long, leading from this ‘wharf’ to the kilns, to allow the heavy raw materials to be moved to the kilns by the shortest possible route.

It is not immediately clear why it was better economics to build two large new kilns and transport the two essential bulky ingredients – limestone and coal – from Newry by lighter, rather than just importing the finished product, the lime. Perhaps the Close estate sold the lime produced at Gamble’s Bridge to tenants at below market prices?

Not Just Prizes, Medals Too

As well as ‘premiums’, farming societies sometimes awarded medals. The late Minnie Savage of Laurel Hill had a D&AFS medal awarded to her grandfather for growing flax-seed in 1866.

Competitive Ploughing Matches

On 7th March 1832, a huge ploughing match was held on Alexander Kinmonth’s farm at Deer Park. Kinmonth was a stalwart of the D&AFS and had just become one of Col Close’s largest tenants. Between them, 71 ploughs ploughed 52 acres in a day! Afterwards, Kinmonth provided dinner for 130+ in the schoolhouse.

The last contemporary newspaper report of a D&SFS event was in November 1876.

Drumbanagher ‘Castle’

The original Drumbanagher House burnt down just two years after the Close family bought the estate. Sometime later, Maxwell Close commissioned the famous Edinburgh architect William Henry Playfair8 to design a very grand new house. It was designed by William Notman, working under Playfair. The foundation stone was laid in 1830 by Maxwell’s young son Maxwell Charles close, and the house was completed in 18389.

At one point, its construction employed 70 stonemasons. It cost of £80,000 – almost as much as Close had paid for the whole estate in 1817. We assume that until that was completed the family’s main residence was still at Elm Park near Armagh.

The Newry Telegraph reported on 24th July 1838:

“On Friday 20th inst., Mr Peter Forsythe, who has been superintending the building of the splendid residence of Colonel Close for upwards of the last eight years, was entertained at dinner at Mr. James Irvine’s, Gerrard’s Pass, and presented with a handsome and valuable silver snuff-box by a few members of the Presbyterian congregation of Drumbanagher, on the eve of his departure for Scotland, his native country…many invaluable services which he voluntarily rendered their congregation, while they were engaged in a rebuilding of their place of worship.”

On 18th October 1838, the Newry Telegraph printed both a grateful letter to Forsyth from Alexander Kinmonth and a formal reply from Forsyth.

The new Drumbanagher House was one of the grandest Irish houses of the 19th century, described in highly florid language by Byrne (1846):

“A magnificent sweep of carriage way leads us through shady groves, where the blackbird teaches her sweet notes to the echo, up to the western front of this chaste and superb mansion. It is of the Italian style of architecture and is considered the finest specimen of that style in Ireland. It is built of Scotch sandstone10. There are several classic statues in pure white marble, of Venus, Cupid, Psyche, &c., on elevated pedestals in the grounds, and many huge vases of sandstone ornamented with sculpture in bas-relief. This castle is a modern building, only a few years completed.

There is a lovely parterre at the eastern front, with delicious walks through the flower beds and rustic seats. The velvet sward slopes gently down to an artificial lake, and then stretches away as far as the eye can see, loaded with stately trees and profuse plantations. As a whole, this is one of the most princely residences in the north of Ireland; art has here gloriously triumphed over nature and raised a paradise in the waste wilderness; even the poorest dweller in the land may enjoy its gorgeous display of beauties freely and unquestioned.

The courtesy of the proprietor in this respect is deserving of all praise, and we hope will be more generally imitated.”

During the time between the old house burning down and the new one being finished, Close was still a professional soldier. He had married in Bath in 1820, and had correspondence addresses at two gentlemen’s clubs, one in Dublin and one in London.

The newspapers of the time often reported the travels of the gentry and aristocracy and there are many reports along the lines of “Colonel Close and his lady wife have departed for…” and “There were joyful scenes in Poyntzpass when the village welcomed the return of Colonel Close and his lady after a long absence…”. The Dublin Morning Register reported in August 1841 that “Colonel Close, of Drumbanagher Castle, is sojourning at Baden Baden”, the famous German Spa near Strasbourg.

Col. Maxwell Close died at Drumbanagher on 16th December 1867.

**** LEGACY ******

- In 1817, would these have been English acres or ‘Plantation acres’, 1.62 times larger? ↩︎

- See “A Local Episode In The Land War” by Joe Canning, BIF Vol 9, 2012 ↩︎

- PRONI records show that in in the mid-1800s, the Close family owned 9,087 acres of land in Co Armagh plus 3,678 acres in Queen’s County (Co Laois), a total of almost 15 square miles. ↩︎

- Described in William Greig’s 1820 report on the Drumbanagher estate. ↩︎

- Greig’s “General Report On The Gosford Estates” is the most complete and detailed such survey and analysis that survives from the era, and was republished in full, with expert commentary, by PRONI in 1976. ↩︎

- Lovingly transcribed in 2022 by Hugh Daly and available ……. ↩︎

- Greig implies that the general (and mistaken) impression that Drumbanagher tenants are “comfortable and opulent” can be attributed to them being strong-armed into inaccurate and obsequious public Addresses to Moore and others by “a few very officious persons who wished to serve or appear to serve their landlord”. ↩︎

- Playfair’s original plans for Drumbanagher House are now held in Edinburgh University Library. Playfair also designed The National Gallery of Scotland, as well as designing Brownlow House for Maxwell Close’s brother-in-law Charles Brownlow, later the first Lord Lurgan. ↩︎

- By the time he moved in, Close would have been aged about 55. ↩︎

- So all of the stone for this huge house was imported from Scotland! Presumably it was transported up the canal and offloaded at Gambles Bridge. ↩︎