Very Expensive Public Servants!

A key provision of the Irish Grand Juries Presentment Act of 1817 was the appointment of a well-qualified County Surveyor for every county, on an annual salary of £300 to £600. This very large salary was thought necessary to raise them above the temptation of bribery and corruption. We can get some sense of how enormous these salaries were for the time; when Dr MacDermott was appointed as Poyntzpass dispensary doctor a full half century later, his annual salary was a mere £80.

First Attempts Fail

A selection board sat in Dublin in January 1818, headed by the eminent English road and canal engineer Thomas Telford. Of the 95 candidates they examined at length, only three were judged to be competent surveyors!

As a result of this debacle, a further Bill was presented to parliament in 1818 to suspend the 1817 Act.

Finally, In 1834 …

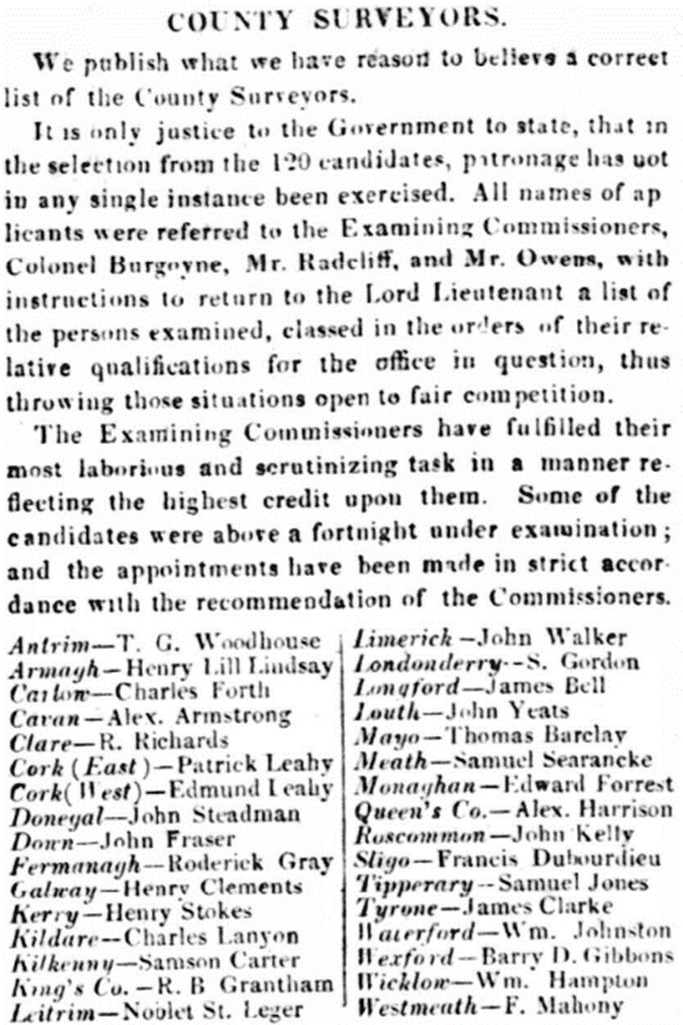

It was not until 17th May 1834 that a full complement of 32 competent and well-qualified surveyors were formally appointed. This announcement appeared in many newspapers.

All of the candidates had undergone a rigorous 14-day assessment during April 1834. This was a remarkable event – it was the first ever set of public appointments in the British Isles as a result of competitive public examinations. It was another 20 years before competitive examinations were introduced for civil service appointments in Great Britain.

The presentment system continued for many more decades, right up to the abolition of the grand jury system in the late 1800s, but at least, with professional county surveyors now in post, actively managing what was worthy of approval and tightening up on sharp practice, the worst abuses of the system by the big landowners began to be suppressed.

It is not surprising that right from the start of the County Surveyor system in 1834, there was almost automatic conflict between the grand juries, largely corrupt and previously answerable to no-one, and the new surveyors, whose posts were created specifically to bring grand jury excess to heel. It was a tough job, requiring very thick skin!

Armagh’s First County Surveyor

Henry Lill Lindsay, younger son of the Bishop of Kildare, was appointed Armagh County Surveyor on 17th May 1934. He wasted no time in getting to grips with his job and trying to fix the abuses and corruption that stemmed from grand jury custom and practice.

A few weeks later, in July, in his first formal report to the 1834 Armagh summer assizes grand jury, Lindsay wrote:

“I don’t consider that any of those private roads will be injured by refusing presentments on them for 12 months, or more; And am of opinion, that two or three of them should be repaired at the public expense; And that others which are really unnecessary, should either be stopped up, or a small presentment granted every three or five years for their repairs…

A less sum than what is now applied for, to keep the roads of the barony of Upper Orier in repair, will keep them, by proper management, in excellent order, and prevent the coach road from Newry to Newtownhamilton, being in that disgraceful state that it is at present…the coach roads in the county of Armagh, are kept in very bad repair, while there is nearly 100% too much paid for the repairs of the private roads.

I am of the opinion, that re-resentments for the repairs of roads, which will be applied for at the next March assizes, will be lighter, in their fiscal amount, than they have heretofore been, and that the roads will be afterwards better kept.”

This was a clear shot across the bows of the habitually ‘entitled’ grand jurors. He was saying “I know how you’re gaming the system, and I’m making it public. Stop it – I won’t approve any more presentments that would only serve vested interests. I’m transferring public money to improve the roads that connect the major centres of population, and benefit everyone through trade and commerce.” His choice of the phrase ‘private roads’ seems very deliberate.

A few months later, in his report to the 1835 spring assizes, Lindsay said of the roads of the Barony of O’Neiland West – the northern section of Co Armagh which borders Lough Neagh:

“The roads of this Barony are too numerous, and many of them are unnecessary, or only of some little private importance…As there are so many roads in the Barony – more than ever be repaired again…for every road you open, you will, in all probability, have to shut up an old road in its stead.”

Lindsay’s interactions with the Armagh grand juries were often combative during his 12 years in post. Their complaints centred on his ability to also run a private practice while employed by the county, but this was not uncommon for the first generation of county engineers, and Lindsay claimed that he spent a very small proportion of his time on it.

In a local context, the construction of a new ‘low road’ north of Poyntzpass in 1836, bypassing Acton, was one of the more sensible developments of that era. Although well known for their quality and ubiquity, the roads of this part of Ireland were, as already noted, also legendary for their steepness and tendency to go from hilltop to hilltop – hardly ideal for horse-drawn traffic. The construction of a new road bypassing Acton hill was advocated1 by Grieg in his 1820 report.

Early Reforms

The Grand Jury (Ireland) Act of 1836 attempted to reform and codify all aspects of the grand jury system as it applied to the spending of public money; its aims included:

- Removing political influence in the selection of grand jurors by requiring them to be selected purely based on their property qualifications, rather than their political affiliations or connections.

- Limiting the power of grand juries by requiring them to act within the law and prohibiting them from acting arbitrarily or exceeding their authority.

- Increasing transparency and accountability by requiring proceedings be held in public.

- Greater efficiency, by reducing the number of jurors required for business to be transacted.

Key provisions included:

- Establishing a central panel of grand jurors for each county, which would be selected by the county sheriff from a list of eligible persons who met certain property qualifications.

- Jurors were to be selected from the central panel for each session of the court. The county sheriff now had to give reasons for his choices.

- Jurors were to serve for a term of one year and could be reappointed for subsequent terms.

- Jurors would be paid two guineas a day from county rates for their services.

- Reducing the quorum of jurors required for the transaction of business from 23 to 12.

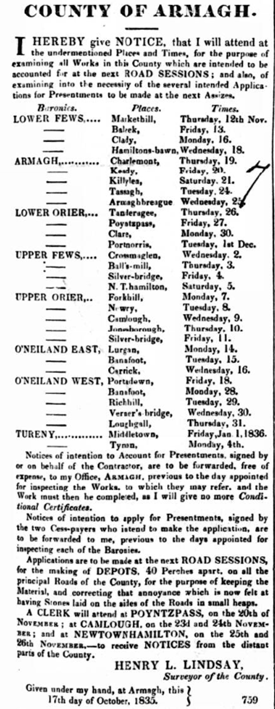

From 1835, Lindsay regularly toured Co Armagh, spending a day at each large town or village, both inspecting road works which had been completed and for which payment was sought, and reviewing promoters’ draft presentments and saying them whether he would support them or not. Such tours were well advertised2 in advance; that at the end of 1837 lasted from 27th November to 1st January – a full five weeks (but he did get the weekends off). He spent 12th December in Poyntzpass.

A few weeks after Lindsay’s 1837 ‘tour’, a special local Road Sessions was held in the principal town of each barony, such as Tandragee for Lower Orier and Markethill for Lower Fews. They considered a large variety of matters; the words are taken almost verbatim from the 1836 Act:

“Applications for Compensation for Malicious injuries; for the support of Dispensaries, Gaols, and other Public Institutions etc…Applications for Lowering Hills, Filling Hollows, or for Gravelling over either or both, or for Rebuilding, Repairing, Altering or Enlarging any Bridge, Pipe, Arch, or Gullet, or Filling or Gravelling over any of such Works, or for Rebuilding or Repairing any Wall, or for Erecting any Fence or Railing for the Protection of Travellers from Dangerous Precipices, or Holes on the side of Roads, or for maintaining any Dispensary, will be considered at the Special Sessions holden for the Barony wherein any such Work or Dispensary maybe locally situated, although the expenses of the same may be proposed to be levied off the County at large.”

Each meeting was overseen by local Justices of The Peace, and the top 100 cess-payers in the Barony were entitled to attend. It was a good start, but he who paid the piper still called the tune – albeit now in public.

Having severely clamped down on spending on very minor roads soon after he was appointed, to focus more on the strategic roads connecting major population centres, in the mid-1840s Lindsay reversed his policy. In his report to the 1845 spring assizes he stated:

“The applications for roads and bridges, &c., amount to £6,950, a large portion of which is for the repairing of Parish roads, which are rapidly increasing in extent, so much so, that it has been found necessary, in several instances, to curtail the expenditure on the broad roads, in order to keep the amount of the County taxation within moderate limits, and to pursue an economical course in the entire system. The consequences are, that the average mileage expenses of repairing the roads is annually becoming less. The circumstances will, I trust, remove the feelings which existed, that the farmers’ roads were unattended to, while money was freely expended on the broad roads.”

He then turned his ire on the road contractors3:

“[I] will now take up another, but not less important subject, that of the due expenditure of the public money; and in doing so I feel great regret in being obliged to state, that all I can say, in endeavouring to urge contractors to the performance of their duties, and all I can do is making them feel, not only the pecuniary loss they sustain, but the penal responsibility they incur, by not attending strictly to their contracts; still the duties are unperformed, and I am, in consequence, in that disagreeable position, that I have no substantive reason to bear me out in certifying a great mass of the accounts.

I am the more fully convinced of the feeling that, in my mind, must exist, with regard to roads, that public money ought to be obtained at a very cheap rate, as on my late circuit over the county, covering a period from the middle of November to near the middle of January, I scarcely met an individual performing public work; this during a period of the year when roads require particular attention, and when they are most subject to floods, and the sudden effects of frosts, and when there was a sum of nearly £10,000 to be accounted for, perfectly astonished me, particularly so, when I considered that I had given due notice of the time of inspection.

The contractors seemed to have altogether forgotten that I was going over the county examining their contracts, and not only to look after the expenditure, but to see that full and adequate value was given for £10,000. This being the case, I had to awake them from their slumbers…[by] the withholding of payments, and I hope, and trust, that in a short time an effort will be produced, beneficial to the public, and of no disadvantage to the individuals, as if they were to spend their time, at a proper period of the year, in attending to the roads, which they afterwards uselessly waste in looking after me for certificates for unfinished work, the roads would be kept in order, and I would be able to say, that nothing could afford me greater pleasure, than to be able to certify every matter in its due course, as I would thereby have the county business in a legitimate and laudable course of action, and the entire arrangement would be so systematic as to create no individual annoyance.”

In other words – ‘If the work is poor quality, or unfinished, I’m simply not going to pay you a penny. You signed a contract and I’m going to hold you to the letter of it!’

Lindsay Is Forced Out

In the end, it was all too much for the grandees of the Armagh grand juries; they forced Lindsay to resign, on the basis (or more likely the pretence) that his private business activities meant that he must therefore be ineffective in performing his public duties. But the opposite seems to have been the case – Lindsay was far too effective in his good management of public money, preventing waste and corruption among the rich and powerful landowners and the road contractors!

Lindsay resigned in February 1846 and moved to Dublin. He was succeeded by Henry Davison, who must have been much more pliable, as he held the post for the next 40 years!

In July 1847, Lindsay was declared insolvent. In 1850, he sued the Newry & Castleblaney Railway Company, and the Bann Reservoir Company, presumably for unpaid debts. He emigrated to Victoria in Australia with his family soon afterwards, and became an insurance agent. He was later involved in surveying the Geelong and Ballarat railway line.

Lindsay Jnr’s Unusual Fate

His son, also named Henry Lill Lindsay, had set up several breweries in Victoria, but lost them due to bankruptcy. He then became head brewer of Melbourne’s Metropolitan Brewery. On 5th November 1895, he was found drowned in a 1,000-gallon vat of beer … with a losing bookmaker’s ticket for that day’s Melbourne Cup horserace in his pocket!

The newspaper report emphasised that after his body had been removed, all of the beer in the vat had been disposed of in the street drains! Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?

The coroner’s verdict was “accidental death, having been overcome by fumes”. This seems unlikely given the losing bet and the fact that he was estranged from his wife and being sued for child maintenance.

The First Down County Surveyor

The first county surveyor of Co Down was John Fraser of Glasslough, Co Monaghan. Like Henry Lindsay in Co Armagh, he was formally appointed on 17th May 18344.

He moved to Downpatrick, and, like Lindsay, perhaps even more so, continued his private engineering and surveying practice. And like Lindsay, this also brought him into conflict with the Co Down grand jury members—Fraser was involved with multiple new Co Down railway lines, including the Newry & Warrenpoint. Fraser lasted 18 years as Down county surveyor before he too was forced out by his local grandy jury.

- In the section entitled General Observations; “Public Roads … if the road was carried along the base of the hill at Acton Demesne two very steep inconvenient declivities would be avoided, much to the advantage of those transporting heavy loads” ↩︎

- The advert also included a warning to road contractors to obey the law and ensure that carters they employed had their name and address painted on their carts in letters at least one inch high! ↩︎

- No doubt he excluded William Dargan from this collection of rogues! He held Dargan in the very highest regard. ↩︎

- Final confirmation of all 32 county surveyors was published at the same time. A full list of names appeared in the Dublin Morning Register on 23rd May 1834. ↩︎