Each electoral district, if populous enough, was also a Dispensary District; after the 1838 act they became part of the Poor Law Unions system. Each had a resident doctor, who also acted as a pharmacist, although the available medicinal remedies were few, and many were of dubious efficacy, sometimes even dangerous. The argument about whether Poyntzpass and Donaghmore dispensary districts should be separate or combined rumbled on for years.

Originally, dispensaries were supported by annual subscriptions from the better off. In Tandragee, in addition to the local dispensary, “…Lord Mandeville maintains a surgeon and supplies medicines for the use of his own tenantry.”1 who would have been the majority of the inhabitants.

Doctors

Dr James Nesbitt

Dr James Nesbitt was Poyntzpass’ resident2 medical man in the period before the dispensary district was created. He decided to emigrate in 1830 and on 10th May a dinner was held in Bennet’s Inn in his honour “on the eve of his departure for America.” Maxwell Close was referred to in toasts as “The Lord of The Soil”3. Nesbitt was presented with a silver plate cup.

A few weeks earlier, Dr Nesbitt’s house was advertised to be let and said to be “a most desirable residence for a gentleman in the Linen trade”.

In his address to the assembled diners, the Rev Black stated that Dr Nesbitt had been in charge of the Poyntzpass dispensary for the previous 18 years, i.e. from about 1812. This was well before the establishment of the Poor Law Unions.

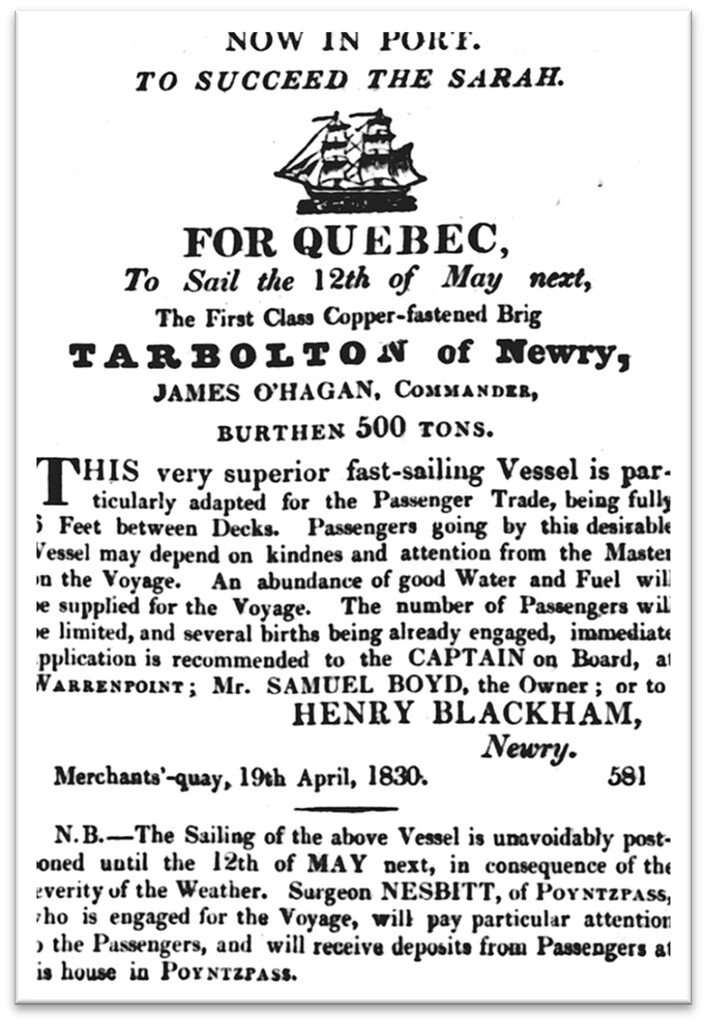

Dr Nesbitt sailed from Warrenpoint for Quebec on 12th May 1830, on board the brig ‘Tarbolton’ and was ship’s doctor during the voyage. If you thought you might want to avail yourself of his medical skills during the voyage, you had to pay a visit to his house in Poyntzpass and pay your deposit.

Dr John Dixon

His successor, Dr John Dixon, was appointed on the formal establishment of the Poyntzpass Dispensary District. On 3rd August 1831, the Newry Telegraph carried his report on the first 10 weeks of operation of the dispensary. In this period, 187 patients were ‘admitted’4 and 448 prescriptions dispensed. If pro-rated for a year, the figures would be 972 and 2,330, although the total for a full year would probably have been higher, as the figures quoted were for just the summer period when diseases are generally less prevalent. Dr Dixon reported:

“It will be pleasing to the Patrons of the Institution to be informed, that of the above numbers, only four deaths have taken place; and these under circumstances over which medicine may be said to have no control. Two of the cases were of fever – admitted after being each a month ill – and in a state of such destitution, as to be without any individual to attend to their wants in other respects, or to administer their medicine to them.

Of the other two cases – one was of disease of the heart, accompanied with paralysis; and the other of general dropsy:5 but the person appeared so extremely weak, that it was not thought advisable to have recourse to any curative means.

“The diseases that have been most prevalent are influenza, fever, and measles: the former has now disappeared, but the two latter still prevail to a very great extent.”

There was an extraordinary public spat a few months later. Dixon had publicly castigated one ‘James MacGill, Surgeon’, for leaving a patient with “a strangulated rupture” (hernia) for much too long before operating and claimed to have intervened and operated himself. MacGill refuted this with an advertisement(!) and an affidavit published in the Newry Telegraph stating that, on the contrary, the delay had been because Dr Dixon had refused to operate for many days, and that in the end it was MacGill himself who operated, assisted by a Dr Travers, and not Dr Dixon. Medical reputations were at stake!

McGill lived locally and is buried in St Joseph’s graveyard; he died from consumption in 1843 aged 38, which means that at the time of the public argument he would have been aged about 26. His son, Dr Edward MacGill was was a surgeon attached to the Dragoon Guards and Light Infantry during the Crimean War, and worked alongside Florence Nightingale.

The Dispensary On Church Street

An 1836 report on the recent inspection of the dispensary painted a very detailed picture of how it operated. It was more than a combined doctor’s surgery and pharmacy; the small premises in Church Street also had space upstairs for four in-patients – in effect a tiny cottage hospital.

“The most distant point which the medical attendant is expected to visit is about four miles. The medical institutions within six miles are…Mullaglass, Markethill, Tandragee and Banbridge…The dispensary possesses intern accommodation consisting of two rooms upstairs, with four bedsteads and bedding. The room is not supported by public subscription, there being no fund whatever to keep the ward open, and it is with the greatest difficulty that any patient can be taken into it…patients have been kept there at an expense of less than 4d a day…

A woman lives in the house, who acts as a nurse…the proprietor of the place does not charge any rent for it. The medical attendant…holds no other public appointment, but continues to pursue private practise…The salary of the medical officer is £50 per annum, without any allowance for lodging or board, or any kind of conveyance…He has performed four operations for strangulated hernia; two of the patients died and two recovered…

Patients are seen at the dispensary, and when too ill to come there, are attended at their own houses, in any part of the district; but there are no by laws on the subject, and the medical attendant, at the period of his election, was not informed that it was imperative on him to visit patients in the night.

There is no rule as to vaccination, it is not administered at the dispensary, but the doctor is in the habit of vaccinating all children brought to his residence gratis…he never inoculates with smallpox6 virus, and would not do so…many cases of smallpox about the town, but fatal cases are rare…it is believed that there are persons who inoculate with smallpox virus, and the confidence in the public in vaccination is greatly diminished.”

There is nothing new under the sun!

We tend to think of vaccination as a fairly modern component of healthcare, so It may come as a surprise to realise that local doctors were already vaccinating against smallpox nearly 200 years ago.

The Bennet Diaries claim that James Bennet’s servant boy, Robert McClelland, was the first in-patient in the ‘hospital’.

We are used to midwifes being female – there is, after all, a clue in the name – but in August 1842, Mr James Bryson of Poyntzpass was “found duly qualified to receive [his] diploma in midwifery and the diseases of women and children”. He was the son of Rev Alexander Bryson of Fourtowns Presbyterian Church7 and aged 20, before he received his medical qualification and became known as Surgeon Bryson.

On 27th March 1838, the Belfast News-Letter reported that the Armagh Grand Jury had approved charitable presentments amounting to £41 14s to support Poyntzpass Dispensary in the previous year.

Dr William Moorehead

In January 1843, Dr Dixon was succeeded by Dr William Moorehead. However, after a few years he left for the Hillsborough Fever Hospital.

Dr William Sanderson

On 17th April 1846, Dr William Sanderson was appointed to succeed him. According to James Bennet’s ‘diary’ Sanderson was:

“For many years dispensary doctor of Poyntzpass. Also of Donaghmore. Rented the Union Lodge, grew the best flax…. Died about 1875”

| On 2 August 1862, Patrick Larkin, aged about 40, died a few minutes after bursting a blood vessel while playing handball. The newspaper reported “…although he had lived many years at Poyntzpass, when the coroner…came in the evening nd A to hold an inquest, he found the body lying in a waste-house, into which it had been removed in the early part of the day, no person seeming to care much about him.” INSERT |

Dr Sanderson had been Donaghmore dispensary doctor since 1852 and now served the united dispensary districts of Poyntzpass and Donaghmore. He was paid £100 a year, in the proportion of £38 for the former and £62 for the latter, reflecting the much bigger population of Donaghmore District.

On 4th November 1853 the Poor Law Commissioners enquired of the Newry Union Board of Guardians whether enough lymph for vaccination against smallpox had been purchased from the Dublin Cowpock Institution8.

By February 1859, the Newry Union was once more recruiting for a Medical Officer for Poyntzpass (plus a midwife on a salary of £10 a year) and Alexander Richmond was advertising Dr Sanderson’s former home as being available to rent. A Dr Davis was paid £1 10s a week to act as a locum.

Dr Thomas Shannon

On 29th March 1859, the Newry Herald reported the official appointment of Dr Thomas Shannon, but by the end of 1862, the post was once more vacant.

Dr McBride

On 7th January 1863, it reported that Dr McBride of Newry had been unanimously elected. The newspaper report said:

“Mr McBride is an amiable and highly accomplished gentlemen, who during his residence in Newry has won golden opinions of all classes. Although young in years he has shown himself as skilful practitioner, and we congratulate the people of the district.”

A Tragic Suicide

Just eight weeks later, on 2nd March 1863, his apprentice, Maxwell Rolston, aged seventeen, committed suicide. Apparently, he was “addicted to drink” and having been admonished by the doctor, who found him drunk on the premises, he was afraid the doctor would tell his parents, so he raided the poison cabinet, drunk prussic acid (cyanide) and expired soon afterwards.

Dr McBride stayed for just over four years, so in 1867 the Union was yet again advertising for a Medical Officer, on an annual salary of £80.9 The village’s luck was about to change, and it was to be the end of a long line of doctors who each stayed in post for just a few years.

The next doctor would serve Poyntzpass for half a century and become a local legend. Interviews were held on 4th November 1867 and Dr W R MacDermott was appointed.

==>> Dr W R MacDermott

- Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland, 1838. ↩︎

- It is likely that Dr Nesbitt was not a properly qualified doctor; he was probably the Nesbitt who was the subject of a letter written by W L Kidd, to the Chairman of the Apothecaries’ Hall in Dublin, deploring the lack of regulations and highlighting individuals who, with little or no training, set themselves up as ‘apothecaries’. ↩︎

- An old form of ‘Lord of The Manor’. ↩︎

- ‘Admitted’ probably means ‘seen by the doctor’ rather than admitted as in-patients to the tiny 4-bed ward. ↩︎

- An antiquated term for what we now call oedema – swelling, particularly of the legs and feet, due to water retention. ↩︎

- The safe practice was to use lymph from cattle infected with cowpox. ↩︎

- See “Fourtowns Presbyterian Church” by Griffith Wylie, BIF Vol 2, 1988 ↩︎

- This was established as early as 1800, soon after Edward Jenner’s discovery that inoculating people with lymph from cows infected with cowpox conferred a high degree of immunity against the much more deadly smallpox. ↩︎

- 30 years earlier, the annual salary of the minister of Fourtowns Presbyterian Church was £160 a year! People in the area seem to have rewarded those who saved their souls much better than those who saved their lives! ↩︎