My father, Henry Reside Clarke, bought the property in October 1934.

Henry was born in the family farm In Aughantaraghan on 12th October 1912, to Robert Murray Clarke (1867-1950) and his wife Isabella (Bella) Reside (1874-1965). He was the eighth of ten children. He had four brothers – David (Davy), John, Robert (Bobby) and Thomas (Tommy) – and five sisters – Elizabeth (Bessie), Sarah (Sally), Frances Isabella (Isa), Wilhelmina (Willa) and Florence (Florrie).

Childhood Polio

Aged about 12, Henry contracted polio (also known at the time as infantile paralysis) and was left with a permanently paralysed right leg. He wore a heavy steel leg brace and specially adapted boots for the rest of his life, and always used a walking stick.

Being well down the pecking order of male children, and being physically disabled, he was never going to inherit the family farm, so he became a bookkeeper.

Henry Buys The Property

He bought The Railway Hotel (a.k.a. The Malt Kiln) set of businesses – shop, coal yard etc – from John Kelly & Co on 19th October 1934, for the sum of £225 plus an annual ground rent of £13 17s 8d!1 He had just turned 22. We believe that he borrowed the money from his father, Robert, who by this time was a prosperous farmer. When Robert died 16 years later, his estate was worth almost £10,000.

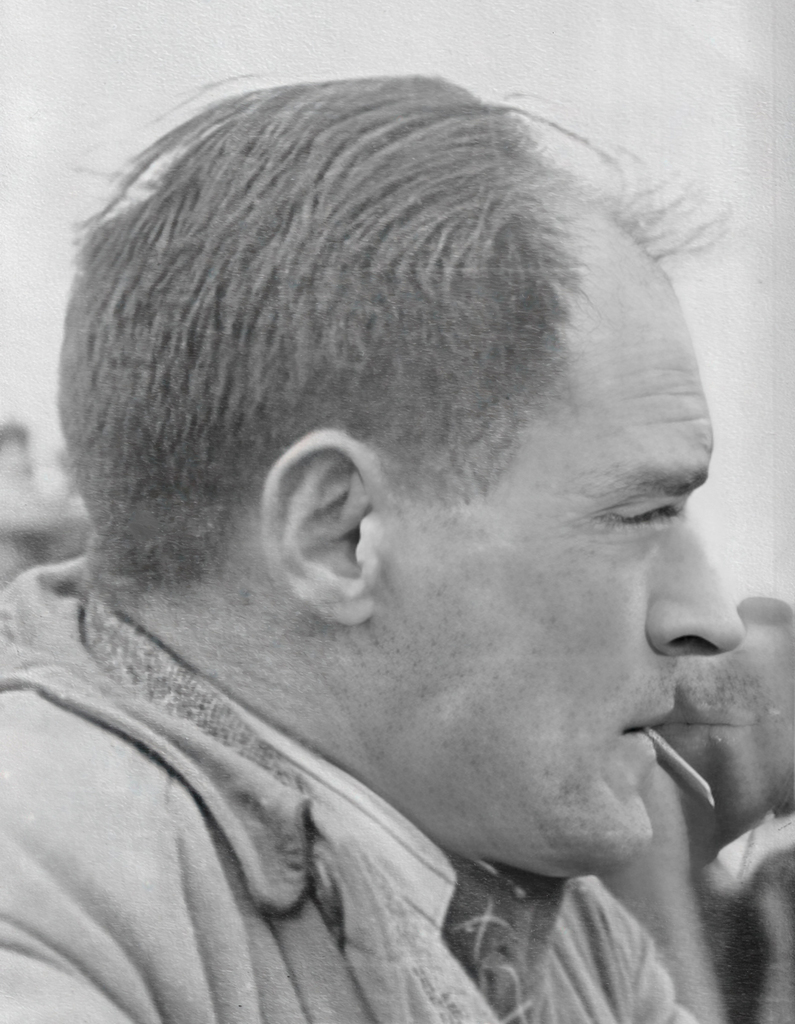

Henry had just turned 22; this must have been an enormous commitment for someone so young in those days. Soon afterwards, he employed his sister Isa, three years his senior, as his housekeeper and to assist him with the businesses. She can seen with him in this photograph, aboard one of the last canal lighters in the 1930s.

In the conveyance, Joseph Seawright is described as as a draper and publican, and the premises are referred to as “The Railway Hotel”. Most of the property consisted of attached outbuildings.

In addition to the house, the east-west range (on Railway Street) consisted of the shop, the ‘entry’ (covered vehicle access from the street to the yard), a couple of storerooms accessed from the entry, and Henry’s woodworking loft above them. The north-south warehouse range was about 25 metres long, and three stories high.

Despite his physical disability, Henry excelled at DIY. He was a skilled carpenter, and made all of the wooden component parts for the two large greenhouses that he had constructed in the garden. He was a wood turner, and converted an old metalworking lathe for the purpose. He also kept bees. He was a keen participant at the annual Newry Agricultural Society’s show, and for decades almost always won the cup for the most first places in the flower and produce section. He was very active in village life, and although he could not play because of his disability, he was an umpire in the tennis club during the war years.

Marries Emma Irwin

On 24th November 1948, he married my mother, Emma Margaret Irwin, at First Drumbanagher Presbyterian Church. He was 36 and she was 27.

She was born and raised on the family farm at Corgary, near Dromantine, and had four brothers – Robert (Bobby), Thomas (Tom), David (Davy) and Albert (Bertie) – and three sisters – Eileen, Myrtle and Audrey. Her parents were Robert James Irwin (1889-1971) and Margaret McClelland (1894-1937).

Henry and Emma had three children in quick succession – Alan (me) born on 27th March 1951, Tom (14th May 1954) and Margaret (15th August 1955). Tom was born with a genetic condition called Noonan syndrome and died, ultimately from its various effects, on 21st December 1999, aged just 45.

Enterprising Couple

Soon after she and Henry married, Emma started a small home bakery in the new kitchen that Henry created in the back of the ground floor. She made Irish soda and wheaten bread, buns and apple and rhubarb tarts in season; what she baked was sold in the grocery shop.

About 3/4 ton of jam – rhubarb and ginger, blackcurrant, strawberry, raspberry, plum, damson, crab apple jelly, blackberry jelly, marmalade, even marrow and ginger – was also made each year, often with the help of aunts Sally, Willa, Isa and Bessie.

Rhubarb, raspberries and marrows were grown in the garden, Tom, Maggie and I collected crab apples and blackberries from the local hedgerows, and we picked large quantities of blackcurrants from the (by then) derelict and overgrown walled garden in the Drumbanagher demesne. Throughout the year, Henry paid local kids a penny each for used glass jampots which we washed and sterilised before reuse in the jam season.

1960s

By the time I was in my early teens, in the 1960s, and helping in the business (as all kids whose parents were farmers or in commerce did in those days), it consisted of:

- The shop, which sold groceries, fresh bread, and hardware.

- My mother’s home bakery, whose products, including the jam, were sold in the shop.

- The garden; this was a large smallholding with two substantial greenhouses. The produce was sold in the shop (and some excess to other local shops) and consisted of, in season … tomatoes, rhubarb, lettuces, raspberries, peas, broad beans, potatoes, leeks, celery, sweet pea flowers, etc.

- The warehouses, which were rented out for the storage of wheat, barley and oats in hessian sacks. They also housed a roller mill where we crushed (flattened rather than ground) grain for animal feed.

- One of the two freestanding sheds by the canal held the coal we sold, as it had done for over 150 years, plus a 500 gallon tank from we dispensed paraffin oil into customers’ own containers. It was still widely used for oil lamps and heating.

- The second shed held our timber stocks.

The Canal Is Defunct

By the time Henry bought the property in 1934, the canal, which had been the reason for its construction, was an irrelevance.

Where the canal bends, immediately south of the bridge and opposite the house, it is much wider than normal, forming a basin and wharf, where other traffic could still pass while lighters were moored. On an old postcard, this is called ‘Poyntzpass Harbour’. Nowadays, this extra width is not immediately noticeable, as the water level is so low.

An old photo of the harbour (possibly another Napier postcard) shows a large wooden crane whose boom extends over the Canal Bank road, with a large lighter on the canal; in the background is a large log pile. You can also see the railway signal box, the original hump-backed bridge, Moody’s lock-keeper’s cottage and what when I was a child was Edmund Loughlin’s small cattle shed.

Lighters could also moor on ‘our’ side of the canal, to be unloaded. The Napier photo of the house and a man and two boys shows a stone edge to the canal. By the 1960s, no visible trace of this remained.

The inland section of the Newry Canal was formally closed to commercial traffic in 1936, but it was not formally abandoned until early 1956. The old stone-built hump-backed bridge was replaced by a flat reinforced concrete bridge in 1951. This also carried an exposed mains water pipe across the canal on an RSJ – I often walked across this pipe, bracing myself against the underside of the bridge, as a quick way between banks. In the 1960s both the water levels and the flow were very low (as the nearby lock gates were decayed and permanently open). With a pair of wellington boots donned, the space under the bridge became my private playground and a great place for amateur dam building.

Death

Henry Clarke died of a heart attack on 19th January 1971, and is buried in the graveyard of Poyntzpass Presbyterian Church, where he had served as an elder.

Trivia

I remember Dad showing me the cheque for one shilling (5p) that he received every two years from the electricity company. It was the rental payment that he received of 6 old pence (2.5p) per year for our side garden hosting the support cable for a pole.

- In 1969, 35 years later, my father ‘bought out’ the ground rent for £195, from the Close estate. So the ground rent must have been payable annually to them ever since they sold it to Jane Frances Whigham in 1859, 110 years earlier. My father had to pay the Estate almost 6% of the purchase price every year! ↩︎