From Prehistory To The Ulster Plantations

The village of Poyntzpass lies on the border of Co Armagh and Co Down, mostly in the former. It is nine miles from Newry, seven miles from Banbridge, six miles from Markethill and five miles from Tandragee. It sits astride the now-abandoned Newry Canal, and the main Belfast to Dublin railway line passes through it.

At the 2021 census it had a population of 632, served by five churches, three pubs and two primary schools.

Geology

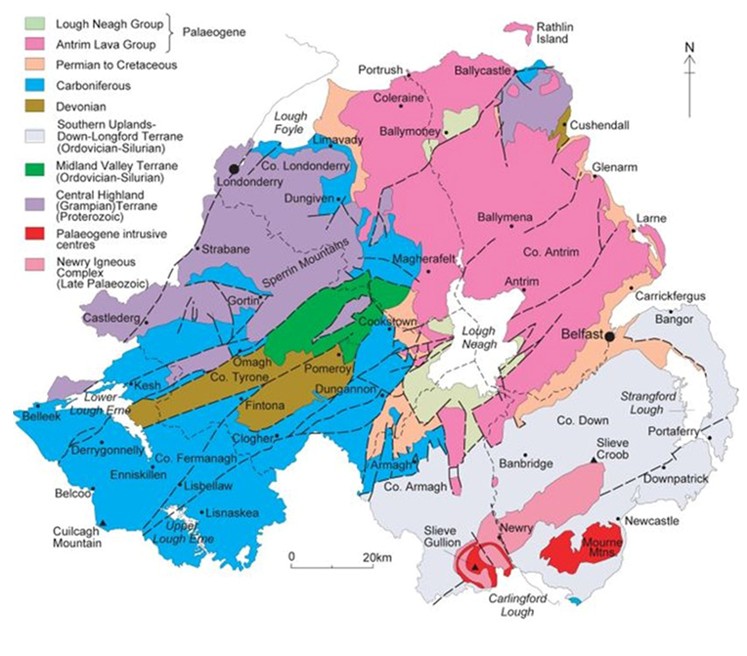

The bedrock beneath Poyntzpass and surrounding areas is mainly ancient Silurian shales and slate, dating back around 300 million years. In parts of County Armagh and North Down, these rocks are overlain by more recent basalt flows from the Eocene period, but in the Poyntzpass area, Silurian formations are close to the surface.

The locally quarried stone traditionally used for house building is predominantly greywacke.

The Ice Ages

The landscape that surrounds Poyntzpass was dramatically shaped by the last Ice Age. Retreating glaciers deposited thick layers of boulder clay (glacial till), creating a distinctive terrain of undulating drumlins—small, rounded hills formed beneath moving ice fields.

Another glacial feature played an important role in the village’s genesis. It sits across a glacial feature known as the Poyntzpass channel —a broad, shallow valley cut by meltwater as glaciers retreated. It was a route for massive subglacial meltwater flows during the Last Glacial Period to what is now Carlingford Lough.

When the last glaciers disappeared about 11,000 years ago, and the level of Lough Neagh had settled, the flow of water almost stopped. Over the following millennia, with changing climatic conditions, this low-lying almost flat corridor slowly transformed into a large peat-filled bog which became known as the Glan or Glin Bog. There was still a steady water flow through the bog, as it drained large areas of the surrounding countryside—we all know just how much rain falls in the locality—but it was much reduced from the immediate post-glacial era.

Prehistoric Times

There were only three places where east-west movement across the middle of the Glan Bog was relatively easy—at modern-day Scarva, Poyntzpass and Jerrettspass. In earlier times, these crossings were known as Scarva pass, Fenwick’s pass and Tuscan’s pass respectively. We do not know who Tuscan or Fenwick were.

Much has been written about prehistoric Ireland and how its landscape and peoples developed after the retreat of the last great ice sheet and the beginning of the Holocene geological era. South Armagh and South Down are rich in stone-age remains1, such as passage graves and dolmens.

Some other visible traces from the last two to three millennia survive in the local landscape, most notably the Dane’s Cast or Black Pig’s Dyke. Locally, this is most visible near Loughadian and is just a small fragment of a large series of defensive earthworks built about 350-400 years BCE2. They are postulated to have connected lakes or bogs, thereby forming a continuous set of defences.

Local Archaeological Finds

Artifacts found or remaining in the area from those prehistoric times include:

- Loughbrickland lake contains the remains of a crannog, a man-made defensive artificial island which is probably about 2,000 years old.

- A gold torc was found in the townland of Drumasllagh in 1794. It was claimed as treasure trove by Bishop Percy of Dromore and finally ended up in the possession of the Parsons family of Birr Castle, Co Offaly.

- The Historical Memoirs of The City of Armagh, 1819, states

“In the bed of Loughadian, which was drained upwards of seventy years ago by the late William Fivey, Esq. a variety of instruments of war, such as celts, spear heads, brazen swords, basaltic hatchets, , and missile weapons of flint, have, from time to time, been found in cutting turf; and a curious boat was dug up there in the year 1796, It was canoe-like in shape, skilfully excavated, and formed out of an immense trunk of solid oak.”

Loughadian (Loch an Daingin) means “Lock of the stronghold” and the remains of another crannog were found there after it had been drained. - In 1814, the skeleton of a giant Irish Elk3 was found buried nine feet deep in a peat moss on John Moore’s Drumbanagher estate. Together, the skull and antlers measured almost 12 feet across and were displayed at Drumbanagher House; the bones were given to Mr. Bell the landscape painter.

- Lewis (1840) reported “In 1826, a canoe formed out of a solid piece of oak was found in Meenan bog; and in a small earth-work near it were several gold ornaments, earthen pots, and other relics of antiquity.

Mediaeval Times

At some time 1100-1200 CE a castle was built near what is now the junction of William Street and Loughadian Road. This is referred to4 as “The 12th Century Loughadian Castle”. It appears to be largely undocumented – we do not know who built it, what its ground plan was, nor how militarily formidable it was. On Nevil’s 1703 survey map of the Glann Bog, it is the only building shown at or near the location of today’s village. Harris (1744) says that remains were still visible then and the Ordnance Survey (Second Series) map of 1846-1862 says “Castle (in ruins)” as opposed to “Castle (site of)” which implies that parts of the ruins were still visible above ground. We do not know when these last visible traces disappeared.

The origin and history of the village and the area are closely tied to the history and fortunes of the large landowning families of the area. Before 1600, these were the old Irish septs of O’Hanlon5 to the north and west (based around what is now Tandragee) and Magennis to the east (based in the Loughbrickland area).

The Ulster Plantations, beginning in the early 1600s, saw the arrival in the area of the English Poyntz and Moore families, the 1700s were the age of the Stewarts and Hannas, and in the 1800s the preeminent family was the Closes. We will look at those families and their impact later.

The Nine Years War And The Plantation Of Ulster

The area around today’s Poyntzpass only really enters the easily accessible historical record about the time of the end of Tyrone’s Rebellion, or the Nine Years War, of 1593 to 1602.

The war began when Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, organised the leaders of many of the other Irish septs to oppose increasing English control in Ireland. It was a long and bloody war which came close to bankrupting Queen Elizabeth’s England. It went badly for the English until the arrival in Ireland of Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy in early 1600. He reorganised and motivated the English troops, and after his victory at the battle of Kinsale in January 1602, the writing was on the wall for O’Neill and his supporters. The last few rebels capitulated in April 1603.

But Queen Elizabeth I had died just a few weeks earlier, and James VI of Scotland was crowned King James I of England in July 1603. James took a much more pragmatic approach to the Irish and most of the prominent rebels were pardoned, and had their lands restored. With the Flight of The Earls in 1607 the last vestiges of serious Irish opposition within the island were gone, and the plantation of Ulster – the ‘granting’ of lands appropriated (stolen) from native Irish families and clans to English and Scots settlers – now began in earnest. The process was known as escheatment.

Tyrone’s Ditches

One local remnant of the Nine Years War is Tyrone’s Ditches, a set of defensive earthworks. They were built by supporters of Tyrone to prevent Sir John Norreys from approaching from Newry and Dundalk. Interestingly, the Earl of Tyrone’s third wife was Mabel Bagenal who was a sister of his opponent Sir Henry Bagenal who was mortally wounded at the Battle of The Yellow Ford.

Rev Andrew Stewart, a Presbyterian minister from Donaghadee, writing6 in the latter half of the 17th century, had a rather sceptical view of planters, even though his own father was one.

“From Scotland came many, and from England not a few; yet all of them generally the scum of both nations, who for debt, or breaking and fleeing from justice, or seeking shelter, came hither…and in a word, all void of Godliness…yet God followed them when they fled from him.”

Dividing The Spoils Between Church And King

To quote from the website askaboutireland.ie:

In 1609, a commission of officials escorted by an armed force toured West Ulster. They were accompanied by surveyors who drew up maps which divided the land into two types – church land and king’s land. All church lands became the property of the protestant church or Trinity College7, Dublin. The king’s land was divided into estates of 1,000 acres, 1,500 or 2,000 acres. Three kinds of people were given these estates:

- Undertakers

Rich English and Scottish men who could afford to bring at least 10 families from England and Scotland. They were allowed to let “native Irish” tenants farm their land. The annual rent for 1,000 acres was £5 6s 8d. - Servitors

English soldiers and some officials who had served Queen Elizabeth or King James in Ireland. They could take on a maximum of five native Irish tenants. The annual rent for 1,000 acres was £98. - The Deserving Irish

Those landowners who had not taken part in recent rebellions against the Crown. They, in turn, were allowed to have native Irish farmers on their land. The annual rent8 for 1,000 acres was £10.

Each undertaker and servitor had to agree to build defences. A bawn, or stone wall surrounding a courtyard was sufficient for a servitor. However, an undertaker with 1,5000 acres had to build a stone house inside the bawn; a settler with 2,000 acres had to also build a defensive tower. These buildings were intended as strongholds against any likely attacks and uprisings by the disgruntled native Irish.

An excellent account of the local Irish septs and families, both pre- and post-Plantation can be found in Ciara Murphy’s article9.

Carew’s & Pynnar’s Surveys

In 1611, Sir George Carew was ordered to carry out a survey of Ulster, and to report on the progress of the Plantations. He had been the English Lord President of Munster and was a major figure on the English side during Tyrone’s rebellion.

Carew travelled throughout the province in August and early September 1611. In his report, he lists in detail how many acres in each county have been allocated to each category. In Co Armagh, he listed 42 undertakers, six servitors (of which one was Charles Poyntz) and eight ‘natives’.

In 1619, Captain Nicholas Pynnar spent four months carrying out an even more detailed survey, to once more report on the progress of the Plantations.

- See “Archaeological Sites in Aghaderg Parish” by John Lennon, BIF Vol 1, 1987 and

“Ancient Stone Monuments of South Armagh” by Brian McElherron, BIF Vol 12, 2013 ↩︎ - ‘Before Current Era’, a religiously neutral equivalent to the old BC (Before Christ). ↩︎

- Not a true elk, but an extinct member of the deer family, related to the fallow deer. Another set of antlers was unearthed by George Anderson of Drumsallagh in 1965. ↩︎

- In Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council Local Development Plan Paper #14, April 2017. ↩︎

- See “The Rise And Fall of The O’Hanlon Dynasty” by Neil McGlennon, BIF Vol 3, 1989 ↩︎

- Quoted by Rev George Hill in his commentary on Pynnar’s Survey. ↩︎

- After the sale of the Close Estate to its tenants ca. 1900, Trinity College sued Maxwell Close for a large sum of money they claimed he owed them because of these historical rights. This seems to relate to his Brootally Estate, not Drumbanagher. ↩︎

- It is unclear why the rent per acre charged to servitors was so much higher than undertakers or natives. ↩︎

- See ‘Local Aspects of the Plantation of Ulster’ by Ciara Murphy, BIF Vol 12, 2013 ↩︎