Local Labour

In the great age of British canal building, the second half of the 18th century, most canals were built by itinerant labourers called ‘navigators’ – navvies for short – who moved from one canal to the next. And when the railways started to appear from the 1820s onwards, the navvies built them too. However, in the 1730s this tradition had not yet been established and locals were hired as unskilled seasonal labour. On 27th February 1732, an advertisement appeared in the Dublin Journal recruiting labourers for the Scarva, Poyntzpass and Jerrettspass sections of the canal. They had to provide their own tools and would be employed in ‘the season’ between April and August. Similar adverts appeared in 1732 and 1733.

Canal-building at this time of year suited everyone. Earlier in the year, the labourers would be working in the fields planting crops, and after August they would be needed to bring in the harvest; it was a slack time of year for farm work. It was obviously also much drier and warmer than in winter, and much more suitable for working in what was still a huge bog with a steady flow of water.

Locks & Water Supply

Taking boats downstream has never been a problem – it’s moving them upstream against the flow that is difficult! This is where the pound lock, an enclosed lock with two pairs of gates, becomes important. Before pound locks became common in the great canal era in the British Isles, many rivers had been made more easily navigable by the building of staunches or flash locks. However, these are very wasteful of water and moving a heavy boat through the fast-flowing water of an open flash lock requires a lot of man- or horse-power. Pound locks, though much more expensive to build, are much more economical with precious water and provide faster, easier passage for boats.

The Newry Canal is often described as the first ‘summit level’ canal in the British Isles. So, what is one of those? Every time a boat passes through a lock, the water lost to the lower level must be replenished, so there must be a steady supply of water to the highest section of the canal – the summit level. Often this is at one end of a canal, and it is often a natural river. But sometimes the highest elevation along the canal is not at one end but somewhere along its length; this is where the top-up water has enter it.

In the case of the Newry Canal, Lough Shark, sitting 80 feet above mean sea level, was adapted for this purpose, and a sluice was built to feed water into the canal in a controlled manner. Of course, the canal did not solely rely on Lough Shark; numerous small streams along its length also fed it as they could no longer flow into the Glann Bog. One example is Gribben’s River which these days flows unobtrusively through Poyntzpass and enters the canal through an arch beside the bridge.

Each lock on the canal (except …..) had a full-time lock-keeper, who lived in a tied cottage built beside the towpath, alongside the lock. There was also a cottage for the Lough Shark sluice-keeper, on the site of the current visitor centre a mile north of Poyntzpass.

Fifteen locks were built along the length of the canal. They were all of near identical dimensions—44ft long, 15ft 6in wide, and from 12ft to 13ft 6in deep—as the dimensions of the smallest lock on a canal determines the maximum size of boat that can traverse it. The lock chamber walls were all built of high-quality limestone blocks brought from Benburb, via the River Blackwater and Lough Neagh, although the splayed ends immediately upstream and downstream of the gates were initially built from brick. The bottoms of the locks were lined with pitch-covered deal planks, two inches thick. These prevented the inrushing water from scouring the lock bottom and undermining the foundations.

Poyntzpass Lock

Poyntzpass lock was the deepest, as it was there that the fall in level was greatest. That also lead to a special design being used; water from the higher level entered the lock chamber through channels built into the walls rather than via lifting paddles built into the gates. Some years later these poorly-constructed channels began to crumble, endangering the whole lock, and were replaced with conventional lifting paddles installed in the gates.

The ‘Back Drain’

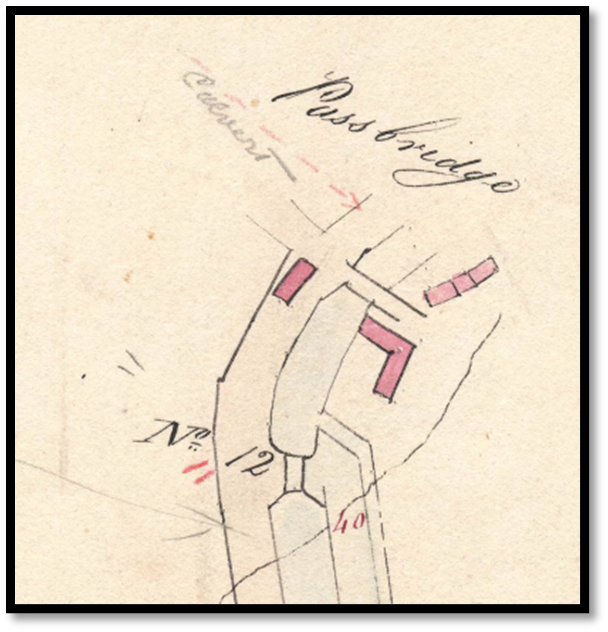

Too much water in winter causes very different problems for a canal; it could overflow the upstream gates of a lock, making passage very difficult. And if it overflowed the banks, they could erode, and a catastrophic breach occur. This is where the ‘back drain’ or ‘county1 drain’, which runs parallel to the canal, came into play. Its role was to carry off excess water in winter, and if it too overflowed, the worst that could happen was that some of the already very boggy land adjacent to the canal would be flooded. It protected several locks downstream from Poyntzpass. Before it was filled in for the construction of the new Poyntzpass Baptist Church, there was a very obvious lower section of bank on the Co Down side of the canal, just above the upper lock gates, where excess water from the summit level between Poyntzpass and Terryhoogan could enter the drain. This can be seen clearly on James Byrne’s 1831 survey of the canal (opposite)2.

It is likely that major sections of the drain were completed before the main channel was dug. If, after its completion, a temporary coffer dam had been built immediately ‘upstream’ of where the Poyntzpass lock was to be built, and the water diverted down the drain, then much of the water would drain from several miles of the section of the Glan Bog to the south of Poyntzpass, making construction much simpler, and of course cheaper. Indeed, looking at the course of the drain north of Jerrettspass on Google Earth, we can see a very sinuous watercourse, whereas elsewhere it is very linear. It is likely that in this area the old Glann Bog watercourse was well enough defined and free-flowing to simply be incorporated into the drain with minimal additional effort.

Lighters, Not Narrowboats

When we think of canal cargo boats in the British Isles, we tend to picture traditional English narrowboats. However, the lighters or barges used on the Newry Canal were much wider, with a deeper draught, more like the large lighters that plied the broad rivers of the East Anglian fens. They had a maximum draft when laden of 5ft 2in. As a consequence, the locks are very much wider than most English canal locks. However, one disadvantage of a wide lock is that it takes much more water to fill it each time a lighter uses it, which in turn puts a heavier demand on the water supply to the summit level.

Pulling a lighter by horse was obviously impossible once it reached Lough Neagh, so, to cope with that part of the journey to or from the Tyrone coalfields, each lighter had a mast so that it could be sailed on the lough. However, the mast was kept lowered while on the canal because of bridges.

- It marks the boundary between Down and Armagh for much of its route between Poyntzpass and Jerrettspass. ↩︎

- No 11 lock is incorrectly marked as No 12. ↩︎