Before we turn to the Close family in the early part of the 19th century, let’s look at how first Acton and then Poyntzpass evolved under the stewardship of the Poyntz and Stewart families in the previous two centuries.

Maps – Surprisingly Unreliable

Before about 1800, we have to rely on old and often quite inaccurate maps to indicate just how extensive Poyntzpass was (or rather, was not!).

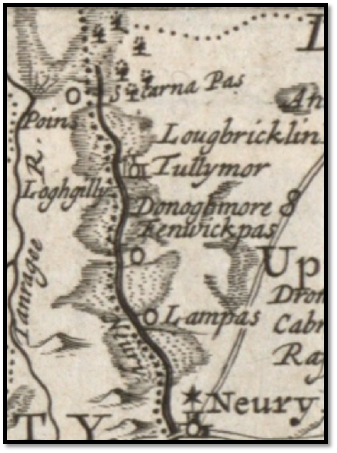

The earliest properly surveyed map of Ireland is that from William Petty’s Down Survey of 1655-56. (right). The site of today’s Scarva is labelled “Scarna Pas” (sic), that of Jerrettspass as “Lampass” and of Poyntzpass as “Fenwickpas”. It is interesting that it shows a very distinct major river, no mere stream, stretching from just north of Scarva all the way past Newry, to the sea. It flows through and drains almost all of the very extensive Glan Bog.

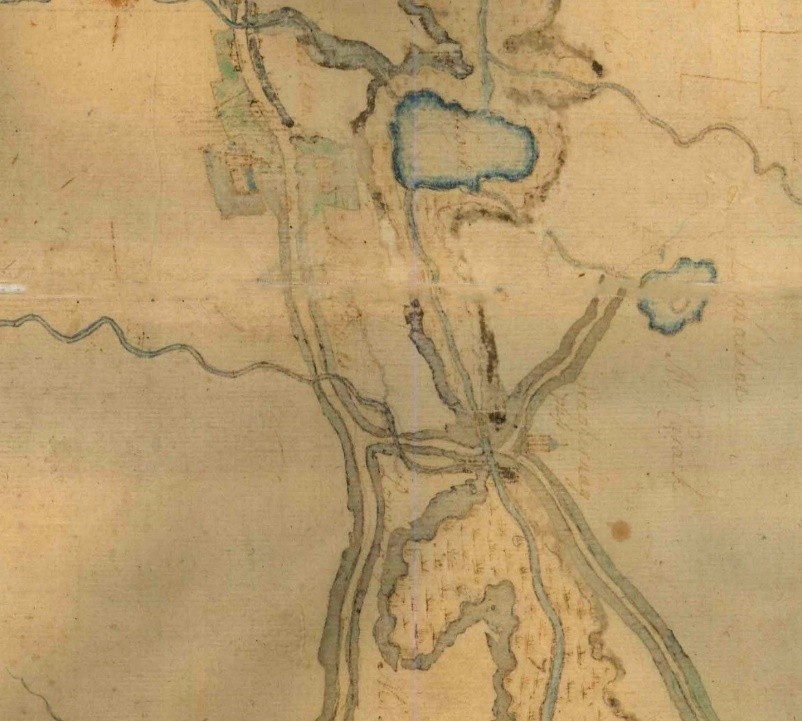

Nevil’s ‘Mapp of The Glann Bog’ (below) of around 1700, was produced as part of his survey of a possible canal route linking Lough Neagh to Newry. A small extract from that of the area around present day Poyntzpass is shown below.

Things to note on the map:

- The bog is very narrow at Poyntzpass, so it’s unsurprising that it was a traditional crossing-place.

- Although Acton, Loughbrickland, Tandragee and other villages and towns are shown with quite a lot of detail, often even individual houses, there are absolutely no buildings shown in the immediate vicinity of today’s village, with the single exception of the old castle.

- The main roads are as they are today, except for the Markethill road which did not exist at the time.

- As on the 1655 Down Survey map, the watercourse through the bog is depicted as being well defined, a proper river.

- Lough Shark is an integral part of the ancient waterway rather than just being connected to it; water enters at the NW corner and flows out at the SW corner.

- The small river through the village is shown crossing what is now Railway Street and entering the bog downstream of the crossing, rather than upstream.

The pass is labelled, but neither as Poyntz’s or Fenwick’s – something like Fraghernag (the first two letters are indistinct). It may just be a contemporary spelling of Federnagh, the townland in which it lies. If so, this would emphasise that the location was unimportant other than as a route across the bog. The map gives no clues as to the physical nature of the crossing, although as we saw earlier, there was a wooden bridge there by 1660.

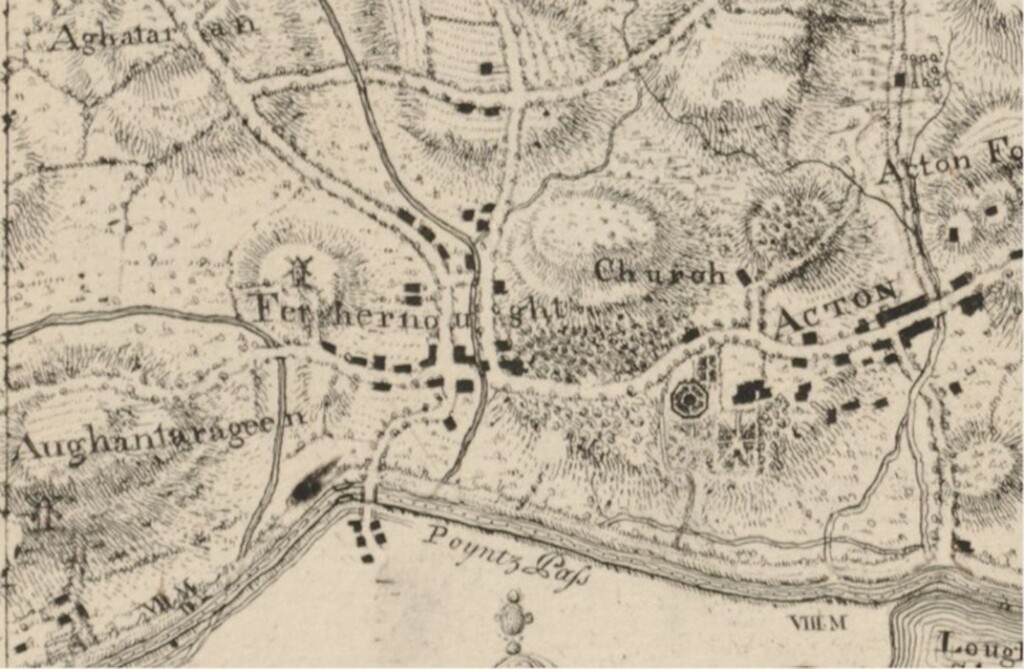

In John Rocque’s 1760 map1 of Co. Armagh (above) the familiar village layout already seems well-developed, despite the assertion by Lewis (1849) that development did not really start until about 1790. It is difficult to know whether each rectangle is meant to represent an individual house or perhaps just designed to give an impression of the village.

The words “Poyntz Pass” appear on the other side of the canal, in Co Down, which Rocque was not mapping, and seem to be the name of the pass through the bog rather than being the village name. The name of the townland, Fenhernought (Fedrenagh) is much more prominent, and the name Acton is even more prominent.

Two other features which are very prominently marked are the windmill overlooking the village and the formal gardens at Acton House. Another windmill is shown on the hill at Aughantaraghan, but no visible trace of this remains today.

Wilson’s ‘Post-Chaise Companion’ (1820) makes no mention of Poyntzpass but does mention Acton. However, Wilson seems more concerned with listing villages in the context of the houses of the gentry who live nearby – especially the ~600 subscribers who paid for the production of the book!

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the counties of south-east Ulster, mainly Armagh, Down and Louth, saw a flurry of building relatively high quality by-roads under the presentment system. Some of the earliest (relatively) accurate county maps were purchased, and sometimes even commissioned, by county grand juries, who controlled the expenditure on roads. We shall look at both grand juries and the presentment system in much more detail later.

When interpreting old maps, as with so many old documents, one should think about why they were created, and who the intended audience was. Today, one can buy a large A3 road atlas of the whole UK for about £15; before the days of satnavs, almost every motorist would have kept one in his or her car. But in the 1700s, only the extremely well off would have been able to afford to buy a map or atlas. They are about asserting property and status, and little or nothing to do with travel.

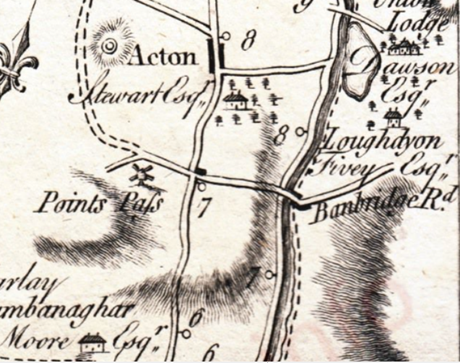

This can be seen more clearly by looking at map 22 of Taylor & Skinner’s 1777 ‘Road Maps of Ireland’. Even allowing for the fact that it is at a smaller scale than Rocque’s map, what we know today as Poyntzpass is only shown as a single building (or group of buildings) at the main crossroads, while Acton is shown as much more extensive. In fact, it seems to show more buildings on the Co Down side of the canal, in what is known as ‘the Far Pass’.

Although the name Points Pass now appears in a more ‘correct’ location, Acton is written in a font that indicates a more significant settlement. Typographically at least, ‘Points Pass’ is depicted as being on a par with Loughadian. The map also seems to show a road (and presumably bridge) of which no trace exists today, crossing the canal immediately north of Lough Shark, leading to Union Lodge.

However, what is very prominent on this map are the names of the large landowners, each next to a symbol representing their grand house. This gives a strong hint as to who Taylor and Skinner’s customers were.

Maps were not for the common man; he would have little use for them and certainly could never have afforded them.

In his much larger scale 1790 Map of Ireland, 13 years after Taylor & Skinner, John Roque does not even record the name Poyntzpass, just Acton. He also omits any road to the east of the canal at Poyntzpass and preferentially records much smaller settlements such as Drumbanagher.

Note also that Fenwick’s Pass, often cited as the old name for the bog crossing at Poyntzpass, is shown south of Drumbanagher, at about the position of Jerrettspass (Tuscan’s Pass). It is clear from all of the above that one cannot rely on these maps to be a detailed and accurate record of the infrastructure of Ireland at the time they were published; they were at best rough approximations.

Evidence points to the most active period of the expansion of Poyntzpass, and when it became more important than Acton, being in the decades spanning the end of the 18th century. Most of the houses and other buildings in Poyntzpass seem to have been built between perhaps 1780 and 1820. Lewis (1849) states:

“That portion of the town which is in the county of Armagh was built about 1790, by Mr. Stewart, then proprietor, who procured for it a grant of a market and fairs…The town comprises 123 houses in one principal street, intersected by a shorter one.”

“…containing 660 inhabitants, of which number, 88 are in the county of Down”

That implies that the Far Pass portion of the village was not part of the original plan, and this makes sense as it was in a different townland and had a different landowner, the Fivey family.

Coote (1804) states:

“The village of Acton, which adjoins the Newry canal, is extremely neat, the houses are new and well built with hewn stone, window stools [sills], and the roofs are very capitally slated and ranged in due and neat proportion. The main street is intersected at right angles, and already nearly one half of the original plan is completely built. Mr. Hanna paid much attention to the improvement of the town during the short time it was under his control, and built a capital malt-house and stores on the banks of the Newry canal, which passes close to the village. The situation of Acton is extremely favourable for trade, and naturally is very beautiful; an excellent inn2 is already established here, and this is now a well frequented stage, which the new line of road from hence to Newry so particularly is favourable to.”

His statement that “one half of the original plan is completely built” is consistent with Lewis’ assertion that Stewart started the construction of the main village about 1790. It also implies that there was a master plan for its construction – something that has not yet come to light.

It is likely that, at that time, the distinction between the newly-expanded Poyntzpass and ‘old’ Acton was less formal than it is today, with Poyntzpass still regarded as part of Acton. The “malt house and stores” that Lewis mentions is the property until recently owned by Henry Clarke and family, on the site of the new Baptist Church; a 1934 conveyance specifically refers to it as “…known as The Malt Kiln…”. It was built around 1795-1800.

The 1830s OSMI3 for Co Armagh presents a slightly less rosy picture of the village:

“On approaching the village from the Newry road, its general appearance is good…The town on closer inspection presents a more unfavourable aspect: the houses are built of stone and largely whitewashed. The following is their number: 3-storey houses 2, 2-storey houses 86, 1-storey houses 5, mud cabins 22.”

One unscientific way of looking at when Poyntzpass became a settlement worthy of separate mention of to look at old newspapers; the earliest mention of the name (in any of its multiple spellings) is in 1818, whereas the earliest mention of Drumbanagher is in 1761, almost 60 years earlier.

It is likely that the small number of dwellings which comprise the Far Pass, on the Co Down side of the canal, were built earlier than those of the main village, possibly by the Fivey Family of Union Lodge, on whose land they would have stood.

Vernacular Architecture

Local vernacular architecture always reflects the building materials that were easily available. Before the 20th century, most buildings were built from Silurian greywacke, a fine-grained, 440-million-years-old, grey-blue sandstone with many veins of white quartz. A broad band of greywacke runs diagonally across north Down and central/south Armagh. When used in the walls of buildings, the greywacke stones were bonded with a lime mortar.

Local buildings4 included the slate-roofed two- and occasionally three-storey terraced houses of the village, small two- or three-roomed stone cottages (often thatched) and occasional mud-built hovels.

We do not know the location or locations where most of the stone used to build Poyntzpass’s houses was quarried. It may have been quarried locally from small outcrops, but the nearest current greywacke quarries5 are just south of Tandragee; the stone belongs to the geological formation called “The Acton Group”.

As the main walls were not built from regularly-shaped brick or dressed stone, they had to be thick just to be stable. Some of the larger multistorey buildings in the village had walls almost 2ft (60cm) thick in places. Internal walls and ceilings in larger buildings were made from lath and plaster. Thin strips of wood with gaps between them were nailed to uprights or ceiling beams and plastered with a mix of lime and grit mortar thickened with animal blood and reinforced with horsehair.

Tandragee Castle was also built from greywacke, but the stone was much more finely dressed than when used in humbler dwellings.

There were slate quarries in Ireland, but most were in Munster, so importing slate by sea from North Wales to Newry and transporting it up the canal may have been just as economical. McCutchen (1965) mentions slate as one of the main canal cargoes in the late 1700s.

It is possible that some older, individual buildings outside the village may have originally been thatched with Phragmites reed, given the proximity of the Glann Bog. These can be recognised by gables that sit above the current slate roofline.

The 1800s

The earliest pictorial evidence we have for the state of development of the village during the 1800s is the view of the village on the cover of Alexander Richmond’s 1831 Close Estate Survey.

The old hump-back canal bridge, the former canal-side warehouses and Moody’s lockkeeper’s cottage (both since demolished), the small bridge through which Gribben’s River enters the canal, the parish church and the windmill (already just a stump without sails) are all easily identifiable, and the main street, or at least one side of it, seems largely complete as far as the parish church.

The building shown to the right of and behind the windmill stump is puzzling. It seems to be large, with several tall chimneys, but there are no remains of any such building visible today, nor any historical record of such a structure.

Richmond’s map is an early example of a cadastral survey, where land parcels are mapped in detail for purposes of ownership registration, rent, taxation etc.

Byrne (1843) refers to John Madden as the principal building developer in Poyntzpass at that date. He is described as a farmer, baker and dealer in spirits, groceries, and provisions; he also appears to have been the postmaster. In November 1859, his name appeared in the Bankrupts & Insolvents Calendar. In December he appeared before the Court of bankruptcy and Insolvency and was unable to provide details of his accounts – as he kept no books! In May 1860, his properties – two farms, three tenements and his business premises – were auctioned to cover his debts.

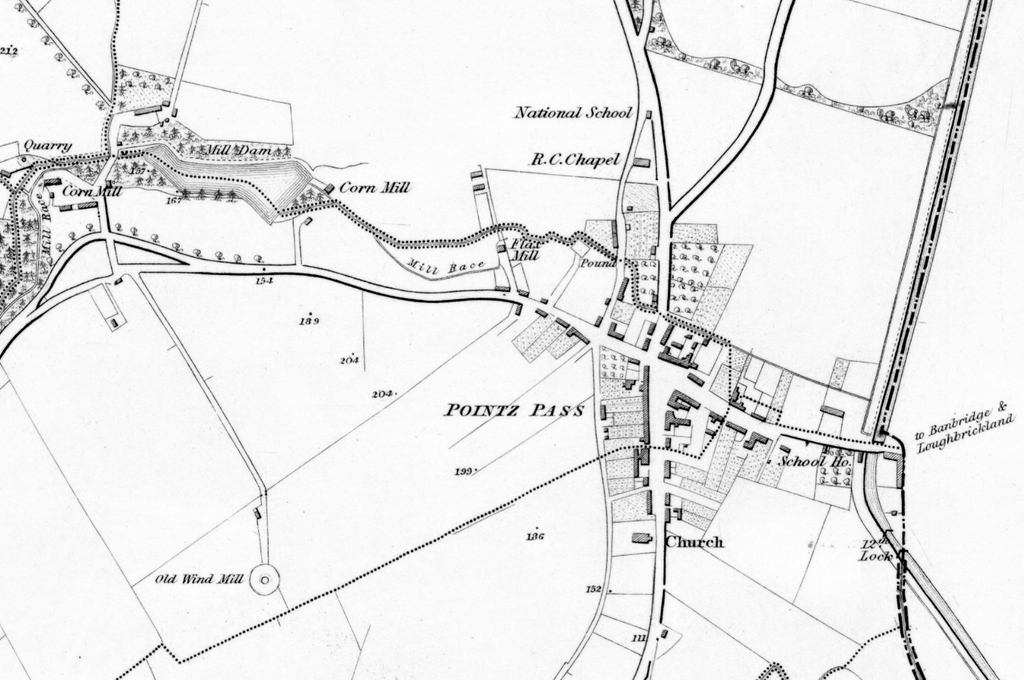

Irish Ordnance Survey

The first properly detailed record of the layout of the village came with the publication of the first Irish Ordnance Survey maps in 1846. Wikipedia states:

“Thomas Colby, the long-serving Director-General of the Ordnance Survey in Great Britain, was the first to suggest that the Ordnance Survey be used to map Ireland. A highly detailed survey of the whole of Ireland would be extremely useful for the British government, both as a key element in the process of levying local taxes based on land valuations and for military planning. In 1824, a committee was established under the direction of Thomas Spring Rice, MP for Limerick, to oversee the foundation of an Irish Ordnance Survey. Spring Rice believed in the importance of Irish involvement in the mapping process but was overruled by the Duke of Wellington, who did not believe Irish surveyors were qualified for the task. Instead, the Irish Ordnance Survey was initially staffed entirely by members of the British Army.

“From 1825–46, teams of surveyors led by officers of the Royal Engineers, and men from the ranks of the Royal Sappers and Miners, traversed Ireland, creating a unique record of a landscape undergoing rapid transformation…when the survey of the whole country was completed in 1846, it was a world first.”

The Ordnance Survey First Series (1832-1846) map of the Co Armagh side of the village (below) compliments the illustration on Richmond’s map, and the two surveys – the public and the private – were probably done within a few years of each other. Richmond had learned his craft as a soldier; he served in the Sappers and Miners for over a decade before leaving the army in 1817.

We know that in some places, local experts were hired to assist with the survey, so perhaps Richmond, given his expertise, local knowledge and former army service might have contributed to the first OS maps of the area.

What’s In A Name?

The British Newspaper Archive is a wonderful resource. At the time of writing, it contains over 95 million digitally scanned, indexed and searchable pages from newspapers and other publications from the UK and Ireland, some from as early as 1730.

Searching these archives is complicated by the fact that the further back in time one goes, the more variation there is in the spelling of the village’s name, and in the names of surrounding townlands and villages. The first occurrences of the various spellings, working backwards in time, that I have detected so far are:

- Points-Pass – February 1784

Belfast News Letter, report on monthly linen market. - Pointzpass – December 1805

Belfast Commercial Chronicle, list of the fairs to be held in the following week. - Pointz-Pass – October 1808

Advert for lease of the canal-side warehouses. - Poyntzpass – October 1809

Advert for lease of the canal-side warehouses. - Points Pass – January 1824

Belfast News Letter, report of two young girls being badly injured in a local flax mill. - Poyntz’s Pass – March 1869

Kilkenny Moderator, report of an orange/green clash in which a man was shot and died.

- Both Roque’s 1760 map, and Alexander Richmond’s 1831 map of The Manor of Acton (see later) are oriented with north to the right, rather than at the top. ↩︎

- Almost certainly Rice’s Hotel, which opened in 1798. ↩︎

- The Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland was a series of contemporary notes made by the first OS surveyors. The OS originally intended to publish these notes for all 32 counties, but this was quickly abandoned due to the high cost. ↩︎

- See “Local Architecture” by John Morton, BIF Vol 4, 1990 ↩︎

- See https://stonedatabase.com/quarries/ ↩︎