Two William Blackers

In the early- to mid-1800s, the name of William Blacker appears frequently in the history of the Poyntzpass area.

In fact, there were two prominent William Blackers in this part of Co Armagh in the first half of the 19th century, and they were almost exact contemporaries. To distinguish between them, they were known as at the time as William Blacker of Carrick and William Blacker of Gosford.

They were only very loosely related, many generations earlier. Both were prominent enough to serve on Armagh Grand Juries and often did so together. This meant that they were both considered to be among the top few dozen most important men in Co Armagh at the time and both merit profiles in the Irish National Dictionary of Biography (see links below).

Lt. Col. William Blacker ‘of Carrick’ (1776-1855)

The better known of the two is the sometime militia officer, versifier, and prominent Orangeman, William Blacker of Carrick. He was born on his family’s estate in Carrickblacker, near Portadown, about 1776, schooled in Armagh and entered the University of Dublin about 1796. However, just before that, he took part in the Battle Of The Diamond and provided detailed written accounts of it. His experiences there led to his involvement in the formation of the Orange Institution.

Blacker was the author of the poem “Oliver’s Advice” which contains the famous line “Put your trust in God, my boys, and keep your powder dry!” He was high sheriff of Armagh in 1811 and was later appointed as Deputy Treasurer of Ireland. He was chair of the Portadown Famine Relief Committee at the same time as Col Close chaired the Tandragee district committee.

His extensive writings, held in Armagh County Museum, are known as the Blacker Diaries, although they are not chronological; they are his musings and thoughts on a large range of topics.

William Blacker ‘of Gosford’ (1775-1850)

The other, William Blacker of Gosford, is less widely known today, but he is much more important in the story of the Poyntzpass area. He was the driving force promoting advances in agricultural methods, not just in Co Armagh but in much of Ireland, in the first half of the 19th century.

In 2003, one of Before I Forget’s long-time contributors, Joe Canning, recorded a short talk about Blacker’s life.

He was the third son of the Rev Dr St John Blacker, curate of Kilbroney and his wife Grace, daughter of Maxwell Close of Elm Park, Armagh, and the sister of Major General Barry Close, and so was a first cousin of Maxwell Close of Drumbanagher.

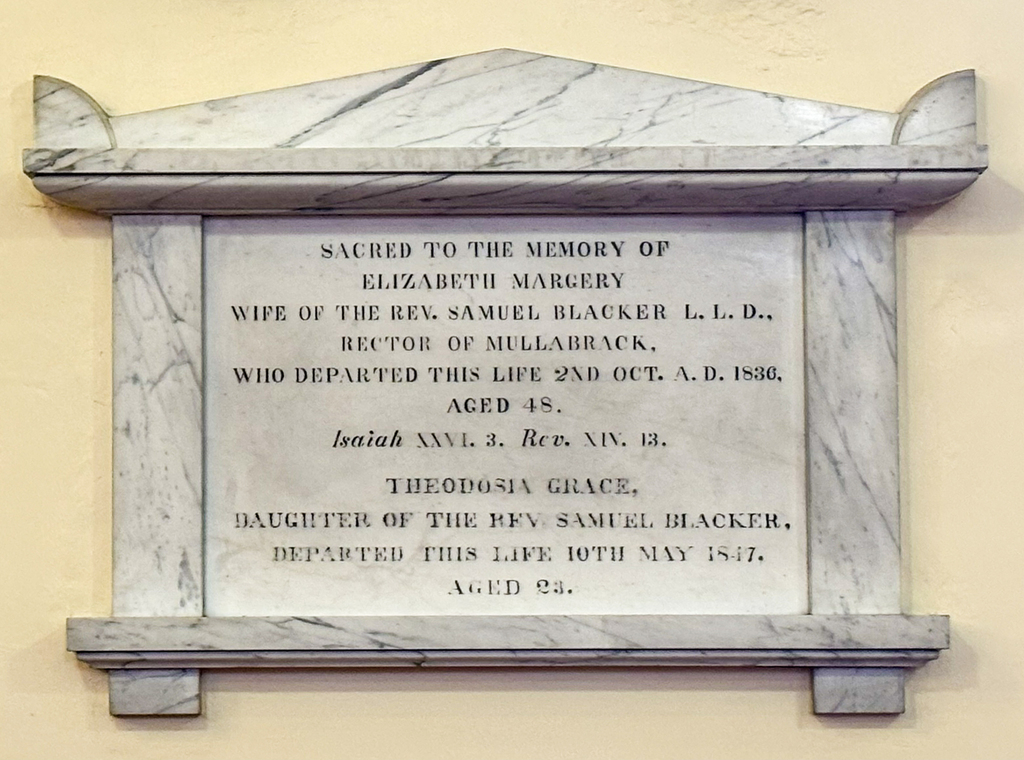

His brothers St John and Valentine both rose to the rank of Colonel in the Madras Army1, one of three huge private Indian armies under the control of the British East India Company. His brother Samuel became Rector of Mullaghbrack, and inherited Elm Park. Another brother, Maxwell, became a successful QC.

He is often referred to as ‘Blacker of Gosford’ as he is best known for his long career as the Earl of Gosford’s land agent. He was also at various times land agent for the Caledon Estate, for his cousin Maxwell Close, for Lord Bangor, and for the Dungannon Royal School estate.

Blacker became a prolific writer on agricultural reform and put his ideas into practice on the estates that he managed.

He also acted as an agricultural recruitment agent, and by 1836 he had brought at least sixty expert ‘agriculturists’ to Ireland, especially from Scotland, to act as educators and supervisors on many of the large Irish estates – not just those that he managed – and to promulgate his agricultural ideas and practices.

As the PRONI commentary on the transcript of Blacker’s copy-out letter books states:

Blacker had a marked predilection for Scottish agriculturalists who could be hired for £30 or £40 per annum in addition to a rent free house. Where land was available for reclamation they were given substantial holdings on which to demonstrate their expertise to show to an agriculturally ignorant tenantry the advantages of improved methods. Another major task for the agriculturalist was the supervision of turf cutting and in particular the depth to which turf cutting was permitted since too deep an excavation prevented drainage and reclamation. This task was made more difficult by the fact that the best turves were found at the lowest levels.

His reputation was such that some of his agriculturists were even recruited to work on some large English estates, including that belonging to Baroness Frances Bassett of Tehidy Park on the north coast of Cornwall.

Early Career

We know little about his life and career before he became a land agent in his late thirties, but one of his newspaper obituaries referred to him as having been “engaged extensively, in early life, in mercantile pursuits.” He is also believed to have travelled widely in Europe during this time.

Blacker’s first appointment as a land agent for a large estate was in 1814, to run Lord O’Neill’s estate at Randallstown.

The Earl of Gosford’s Land Agent

Sometime between 1815 and 1818 he also became the Earl of Gosford’s land agent, on the extraordinarily high salary of £1,000 a year. To be appointed to run such a large estate (about 8,000 acres) and on such a high salary, he must already have had an excellent reputation.

However, despite it being quite common in that era for a land agent to manage multiple estates, Lord O’Neill became unhappy with Blacker having two jobs and dismissed him in 1821. It was probably much more of a loss to O’Neill than to Blacker who remained as agent for the Gosford estate until his retirement about 30 years later.

Maxwell Close’s Land Agent

Col Maxwell Close bought William Hanna’s Acton estate in 1817, and John Moore’s Drumbanagher estate in 1818.

He quickly concluded that the Acton estate had been better managed than Drumbanagher, and commissioned William Greig to thoroughly review the Drumbanagher lands, tenants and farming practices; Greig delivered his report in 1820. Greig had been appointed a few years earlier to produce a similar report for the Earl of Gosford, and it is very likely that Blacker recommended him to Close.

Tributes to Blacker on his retirement suggest that Col Close appointed him to manage his Poyntzpass-area estates about 1822, the same year that the Drumbanagher and Acton Farming Society (D&AFS) was formed.

He now had almost a free hand to implement his ideas in the Poyntzpass and Markethill areas, putting our corner of Co Armagh (perhaps surprisingly) at the forefront of Irish agricultural modernisation at the time. His theories and methods came to be widely adopted in Ireland and beyond.

But Blacker was not only concerned with agriculture and tenants; as a land agent, he was open to all sorts of commercial opportunities that might benefit his employers. In 1826, just a year after the opening of the world’s first steam railway – the Stockton To Darlington – Blacker commissioned a survey and report on the feasibility of a railway linking Newry and Armagh. It was carried out by the young civil engineer William Edgeworth, half-brother of the renowned Anglo-Irish author and campaigner Maria Edgeworth.

Lands Agents And Land Stewards

While a land agent like Blacker might typically manage several large estates, he needed a full-time manager resident on each estate to implement policies, collect rents, advise tenants etc. This was the role of the land steward. Unemployed land stewards regularly advertised their availability in the Farmer’s gazette in the 1880s,

We only have partial information on the Drumbanagher land stewards and their tenures.

- 1833-1845 – William Wood, A farewell dinner in his honour was held on 20th June 1845, after which he departed for “the sister island”.

- About 1857-1865 – James Murray

- About 1910-1911 – W Moorcroft

- About 1928-1936 – Edward Rutherford

The Age Of Farming Societies

The early 1800s were an age of improvement in Ireland, with large landowners and their largest tenants forming farming societies to spread the knowledge of the latest principles of crop cultivation, animal husbandry and land management to their tenants, and holding annual shows and ploughing matches.

But Ireland was late to the game; farming societies had been formed in Scotland from the early 1770s. In 1801, the government awarded £2,000 to help set up the Farming Society of Ireland and a few county societies, such as in Cork, Kerry and Armagh, were founded in 1802.

The heyday of creating farming societies in southeast Ulster seems to have been the early 1820s. The movement became more coordinated in early 1826 when the Belfast News Letter reported:

“… the establishment of a North East Farming Society, by the great landed proprietors and agriculturists of the counties of Antrim, Down, and Armagh…. by exciting a spirit of honourable emulation amongst the farmers of the three counties – by exhibiting in full operation some of the improved agricultural machines now in use in England and Scotland – by demonstrating the practical advantages of a judicious succession of crops and a more skilful system of husbandry than those antiquated methods adhered to with such remarkable obstinacy in various districts of Ulster, and by gradually eradicating deep-rooted prejudices, will do much to meliorate the condition of the people in this province.”

It was renamed the Ulster Agricultural Society in 1903, and the prefix Royal was added in the following year.

The Drumbanagher & Acton Farming Society

The Drumbanagher and Acton Farming Society (D&AFS) was founded in early 1822, and its first ploughing match took place in February or March that year. Col Close was, of course, president, and the committee included some of his largest tenants such as Alexander Kinmonth, who farmed some 80 acres at Deer Park, Drumbanagher. Kinmonth also helped Blacker set up the Richhill Farming Society towards the end of the 1820s.

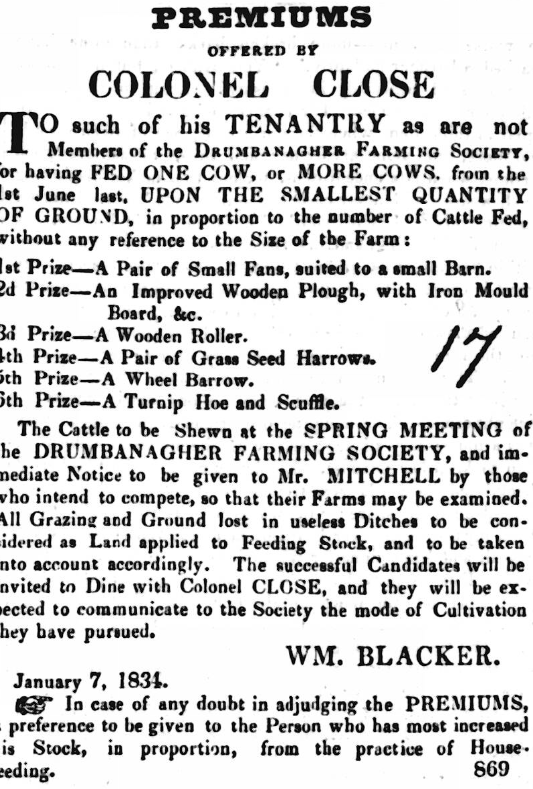

Prizes, Prizes! … But Never Cash

One of William Greig’s recommendations in his 1820 report was the awarding of generous annual premiums (prizes) for a host of different categories on the Drumbanagher and Acton estates, to encourage competition between tenants in improving their farms. This was done right from the start of the D&AFS.

Rather than cash, the prizes were always equipment or materials which could be used to further improve the winning tenant’s farm, such as a plough, a harrow, a horse harness or lime. For example, in the 1833 competition for the tenant who kept “the most cows per acre, fed only on green crops” (Blacker’s key innovation), prizes were awarded to ten of the entrants, ranging from 50 barrels of lime for first-prize-winner Crozier Christy, down to five barrels for the tenth-prize-winner–a huge total of 275 barrels!

Show Rosettes – A Blacker Invention

By 1829, newspapers were reporting ploughing matches all over Ulster. The D&AFS’s 1834 Cattle Show and Ploughing Match was also the first such meeting in Ireland at which a marquee was erected. It also featured another Blacker innovation—the introduction of red and blue rosettes for first and second places.

Annual Dinners

A lavish annual dinner, typically attended by over a hundred tenant farmers and prominent locals, was the highlight of the Society’s year. The prize-winners were announced, a hearty meal was consumed, toasts were proposed, especially to the monarch and Col Close and his family, and speeches were given on how to further improve agricultural practices. These dinners often lasted from 6pm until midnight, or even later!

Other societies were formed locally – the Markethill Farming Society (formally the Markethill Branch of The North East Farming Society) was established before 1828, and the first annual ploughing match of the Union Farming Society, for William Fivey’s tenants, was held in March 1833.

The first newspaper mention of the Newry Agricultural Society reported its first annual dinner in February 1840 – with William Blacker presenting the prizes and, of course, talking about his methods! It also featured talks from several tenants who had prospered by following them. There were innumerable toasts, including “Furrow draining and faithful harvests” and “Turnip cultivation – what makes manure makes money”. Snappy slogans are nothing new.

You can download a transcript of the newspaper report of the Markethill Farming Society’s 1842 annual dinner. It is rich in detail of Blacker’s methods and successes, and the praise of others!

Blacker’s Farming Methods

The key points of Blacker’s system were:

- Drain your land well; start with cheap, easy-to-create furrow-drains for quick results.

- Plant a prescribed rotation of crops, including turnips, rape, clover and vetches, at specific times of the year; you will never need to leave fields fallow.

- Use only the very best quality seeds.

- Keep your animals indoors for much of the year, so that they do not trample what you have sown; feed them on freshly cut green crops.

- Collect the manure and spread it on the land. Cows fed with turnips produce the very best manure.

How Did Blacker’s Ideas Develop?

We know little of how William Blacker came to develop his very detailed farming methods – how much did he adopt from other agricultural improvers such as ‘Turnip’ Townshend?

In England, fully a hundred years earlier, Townshend advocated replacing traditional English two-field or three-field crop rotations—where land was left fallow at least one year of the cycle—with the Norfolk four-crop rotation: wheat, turnips, barley, and clover or ryegrass. Turnips provided fodder for livestock over winter, while clover helped fix nitrogen in the soil, thus maintaining soil fertility. This system dramatically improved agricultural productivity by reducing fallow land and improving yields.

But the Norfolk rotation could not simply be foisted on Ulster farmers; the predominant crops were quite different. Potatoes were the most important crop for human consumption, and oats were the favoured grain crop. And flax, much less common in England, also had to be accommodated.

Arthur Young, visiting Lord Gosford, in the late 1770s, found rotations that were hardly worthy of the name, either:

- Oats for 3-6 years, followed by 3-4 years of grazing, or …

- Potatoes, flax or oats, several years of oats, then flax again. Never sow flax two years running.

Growing turnips as a fodder crop for cattle were at the very heart of Blacker’s methods. They were much more energy-dense than hay and better suited to getting otherwise undernourished cattle through harsh winters in good condition. Better-fed cows produced more milk, which also meant more butter.

Letters to his seed suppliers in England indicate that he was experimenting with his own ideas on some of the Earl of Gosford’s lands in Co Cavan from the very early 1830s.

“Be so good now by the first steam conveyance to ship eight hundred weight of best red clover and one hundred weight of white clover and half a hundred weight of white Globe turnip seed, half a hundred weight yellow Aberdeen turnip seed and half a hundred weight red Tops turnip seed. Desire that they may be kept at the agents in Dublin to be delivered to the order of Mr John Fyfe, Arvagh, county of Cavan who acts for me there and send a letter for him in the ship’s letter bag to say that when he receives that letter receipts will be in Dublin … begging that no delay may take place as the season for sowing clover is fast advancing.“

25th February 1832

Blacker’s System

Blacker described his system in a letter to the Newry Telegraph in February 1834:

“One English acre sown with clover and rye grass will house-feed three cows from the middle of May to the middle of October, and if the land be in good heart, and has a rood [1/4 acre] of vetches to assist it, part of the first cutting may be made into hay.

“The vetches ought to be sown early, and as they are cut, the ground should be planted with rape, taken from a nursery bed sown in the first week of June; or if they had begun to be cut the last week of that month, the rape may be sown ridge by ridge as they’re cut, and in either case if the land has been well manured (which it must be), the crop of rape would be ready for use by the time the frost may have stripped the leaves off the clover, and will be found fully sufficient to feed the three cows until the middle or end of November.

“The turnip crop will now be ripe, three roods of which are an oversupply for that stock to the middle of April, aided by the hay which has been made – at this time right will again be fit for cutting, and will supply food until this succeeding crop of clover and rye grass is again fit for the scythe, when the same system of feeding recommences.

“This is the practise now generally coming into use in this district, and according to it the acre in clover and rye grass, the rood of spring or winter vetches, and the three roods of turnips, making in all two acres, easily keep three cows in excellent condition for the entire year, which is equal to two thirds of an acre for each. The clover should get a top dressing of ashes in the month of January, in order to force on the rye grass, and give a sufficient quantity of hay at the first cutting; and if it again gets a slight top dressing when cut, no three cows of the ordinary size will be able to consume the after growth.”

He omits to say that the main reason “the practise is coming into use” is his use of his position controlling the management of tens of thousands of acres!

Phenology

Nowadays, due to climate change, conditions on a certain calendar date can vary greatly from year to year. So, it is telling that, almost 200 years ago, Blacker was able to be so specific, even down to the week, as to when certain tasks had to be done.

Why Was He So Successful?

I think there are several main reasons:

- First, and very obviously, through absorbing the ideas of others (such as Turnip Townshend) and carrying out his own experiments, he devised a system that worked well for the combination of soil conditions and crop mixtures predominant in the area, and produced big increases in productivity, not just marginal gains, in a very short time, often just 2-3 years.

- His powerful position as land agent on several large estates gave him the power to put those ideas into practice on a large scale, though a judicious combination of carrot and stick.

- Helping to form, and working closely with, local Agricultural Societies, and creating healthy competition between farmers as to who could improve most.

- Employing agriculturists for the estates he managed, and sourcing them for many others, to spread those ideas and give many thousands of farmers, large and small, detailed practical advice.

- Writing pamphlets and short books documenting his methods, having them printed in huge quantities, and selling them at a low price.

- Being very effective at using the newspapers to spread his ideas.

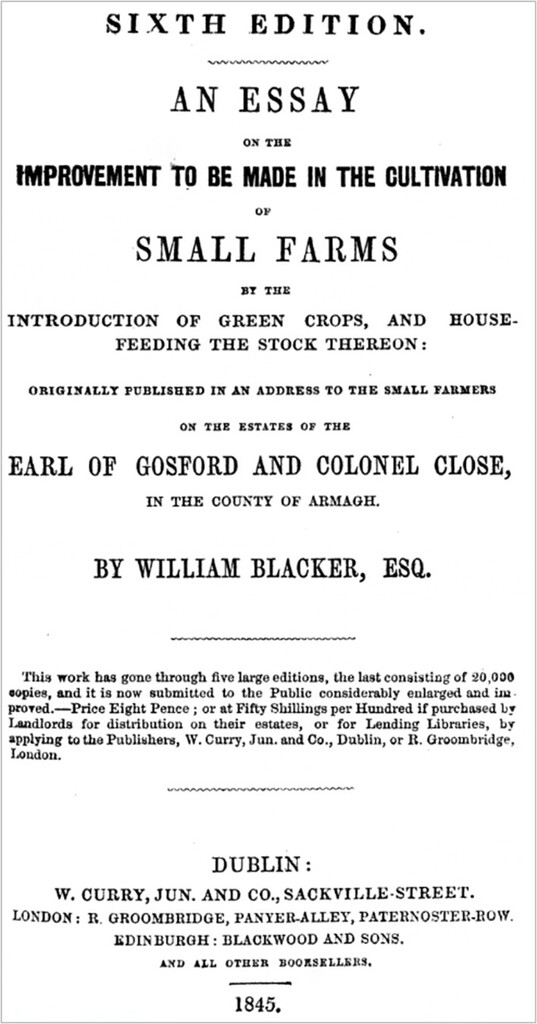

Publications – One Key To Blacker’s Success

The publication of his methods as a pocket-sized ‘how to’ book, and ensuring its widespread distribution, were key to Blacker’s success as an agricultural reformer, which extended far beyond the land under his direct oversight.

His campaign to educate the tenant farmers that he managed had begun in earnest in the early 1830s. In August 1831, the Newry Telegraph reported that Col Close was distributing to his tenants “A well-written pamphlet, by his Land Agent Wm. Blacker Esq., addressed to the tenantry of Colonel Close.”

Many tens of thousands of copies of his “Essay On The Improvement to Be Made In The Cultivation of Small Farms, By The Introduction of Green Crops, And House Feeding The Stock Thereon” were printed. 20,000 copies of the 5th edition alone were printed, and a sixth edition was published in 1845. It was published in octavo format (about 6″ x 9″) and sold for 1s 6d in hardback.

But to ensure maximum availability and affordability, the great bulk of the copies that Blacker’s publishers had printed were cheap paperback copies, which sold for just eightpence a copy, or sixpence in quantities of a hundred or more for landowners and agents who wished to distribute it to their tenants.

Blacker explained his motivation and education methods in the preface to the 1834 edition, and it is worth quoting from this at length.

“For several years I have been turning my attention to the improvement of the tenantry on the estates alluded to, and had made several unsatisfactory attempts to introduce a better system of agriculture by circulating the different works published on that subject, and offering premiums for those who would adopt the improvements recommended; but I had the mortification to find there were no claimants for the prizes proposed, and every attempt I made was a complete failure.

“At length it occurred to me that by writing a short Address to Tenants, their attention might be drawn to the defects of their present system, and by following it up by the appointment of an agriculturist for the special purpose of instructing them, and moreover by permitting him to grant a loan of lime to such as followed his instructions… and by adding my own personal influence, I might have better success.

“Accordingly, the following Address was printed and circulated, with an effect far exceeding my most sanguine expectations… I found the Address to fully answer the purpose intended, and it was generally admitted to contain what was beneficial and right… my own influence being exerted to the utmost, above 300 small famers in each estate were induced to make the trial the very first year.

“… Both the EARL of GOSFORD and COLONEL CLOSE offered premiums for house feeding the cattle; at the commencement there were but two tenants on the estate of the former, and none in the latter, who were able to enter into the competition.

“The 2nd year there were about 50 competitors… and, next year, from the great quantity of clover seed sown this spring, I think there will not be a tenant on either estate who will not feed his stock upon that plan”.

So, it seems that Blacker’s crop and livestock management scheme, outlined in his Newry Telegraph letter, and set out in detail in his ‘Address’, became fully formed in his mind around 1830; by 1835 it was a roaring success, at least locally.

Blacker Tries To Recruit The RDS

In June 1833, according to a report in the Dublin Morning Register, Blacker wrote to the Royal Dublin Society, outlining his agricultural methods, explaining how Col Close and the Earl of Gosford were supporting their adoption by their tenants, encouraged by the awarding of ‘premiums’, and asking the Society to help promote his methods country-wide.

The letter was supported by two detailed case studies written (no doubt with his help) by tenants he managed, which explained how rapidly their financial condition was improving merely by strictly following Blacker’s methods. He also asked the Society to consider rewarding these men for their success, but it demurred. However, the committee praised his efforts and his methods.

In 1834, Blacker was awarded the Society’s gold medal for his essay on the management of landed property in Ireland. He was elected a member of the prestigious Royal Irish Academy in 1842.

Public Support From Others

One of those who enthusiastically endorsed Blacker’s methods was Henry Lindsay (Armagh’s first County Surveyor, who we shall meet elsewhere in this tale) who in his job travelled the length and breadth of the county every year. In July 1834, Lindsay wrote to the editor of the Cork Constitution:

“I have seen the four-course succession crops practised in the County of Armagh, where I believe Mr BLACKER commenced his operations and where I… have an opportunity of examining into the state and cultivation of the soil; and I have seen where the plan has been operated—comfort, cleanliness, industry, and care, which ought… to cause every Landlord to encourage it… Mr BLACKER’s plan … prevents idleness and those who otherwise would be turbulent and depredatory, will become tranquil and happy… ”

“I have seen… an old-school farmer on one side of a road wasting two acres of ground for the support of one cow, while his more industrious and improving neighbour on the other side fed his cow upon two-thirds of an acre, and had the rest of the two acres to support his family – besides having more manure from his cow.”

Although Blacker was initially an opponent of one of William Greig’s key 1820 recommendations—the consolidation of small farms—he later came to support the idea, particularly with the onset of the Great Famine. In letters to newspapers, he urged tenants with holdings of less than about six acres to sell up—or starve!

The Ulster Custom

The fact that Blacker worked primarily in Co Armagh was a significant factor in the rapid adoption and success of his methods. The ‘Ulster Custom’ gave tenant farmers more security in their land tenure, and this motivated them to improve their farms; they had – in the modern phrase – ‘skin in the game’.

Newspapers – Critical To Spreading Blacker’s Ideas

It is interesting to consider the role of newspapers in disseminating good agriculture practice in the period 1820-1850.

Newspapers then were not a means of mass communication. They could not be mass produced; every single page of every issue was individually hand-printed. Most were local; there was no infrastructure to move them quickly around the country.

You did not simply pick up a copy of a newspaper at a newsagent, and hand over a small sum of money; they were funded by subscription, e.g. quarterly, and were not cheap. Subscribers were the middle and upper classes.

Real news was often scarce, so most newspapers got much of their copy by copying what was in other newspapers. Pages had to be filled, and copying other papers’ stories was accepted practice. So, a good article in a local Co Armagh newspaper might find itself repeated in dozens of others up and down the country in the next few weeks.

The proceedings of local agricultural society meetings generated masses of copy. So, a landowner in Wexford might soon learn in great detail what had been said at a meeting of the Markethill Agricultural Society, and so, despite the limited circulation of local newspapers, such ideas and innovation spread rapidly.

Blacker Creates Case Studies

The third edition of Blacker’s slim book was published in 1834 under the title “Address to The Small Farmers on The Estates of The Right Hon. The Earl of Gosford And Maxwell Close Esq. in the County of Armagh”. In this edition, he gives multiple examples—what today we would call case studies—of tenants whose fortunes were transformed by his methods.

Blacker seems to have been very good at getting tenants to write (or possibly dictating to them) detailed accounts of how his methods had quickly transformed their lives for the better. These were then read to meetings of local Co Armagh agricultural societies, reported verbatim in the local newspaper, copied (again verbatim) by other newspapers around the country, and read by large landowners from Donegal to Cork and Mayo to Meath within a few weeks. And, of course, the landowners were constantly looking for anything which might increase the profitability and value of their estates.

So Blacker’s ideas spread quickly throughout Ireland during the 1830s and early 1840s, via local newspapers, his agriculturists and the distribution of his book.

Turnip Rustling!

Blacker’s championing of turnips as a vital crop in his fresh-cut green fodder scheme had unexpected consequences; as more farmers grew them, organised gangs started to steal ready-to-harvest turnips from fields at night! A Dundalk farmer wrote to the Newry Telegraph in December 1843, calling for increased sentences for turnip thieves:

“… many are now advocating the growth of turnips and other green crops… It is a well-known fact that many, very many, in the country are deterred from cultivating that most excellent root, the turnip, in consequence of the quantity stolen where there are not watchmen placed for their protection”

He complained that while the maximum sentence for wholesale organised turnip theft was just one month in prison, a child could be transported to Australia for seven years for stealing a single penny!

Blacker’s Wider Influence

Blacker was an important witness to the Devon Commission which investigated land lease reform in 1844. Jonathan Binns, a Commission member, recorded:

“The system of Mr. Blacker… is first to level the old crooked fences and make straight ones, as a division between each occupier, allotting a square piece of land, consisting of about four statute acres, to each person; and as the tenants were in the last stage of destitution, he found it necessary to provide them with lime and seeds, as a loan, without interest; opening an account with each one of them on their first entering upon the farm. A person called an Agriculturist looks after the agricultural department, weighs out the seeds, and instructs the people in the cultivation of their farms.”

This was not some mere aesthetic consideration; straight fences and rectangular fields with parallel sides made ploughing less time-consuming, freeing the farmer for other tasks. After seeing the results of Blacker’s system of cultivation for himself, Binns wrote:

“I could not help regretting, when I encountered so much misery during my subsequent journey, that this system was not more generally adopted. If poor laws had been in operation previously to these cottiers2 thus settled, they would all undoubtedly have become a burden on the parish; but by the means pursued under Mr. Blacker’s plan, they are enabled, not only to provide competently for their families, but to increase the rental of the estate”.

A cottier was a tenant who paid his rent totally or in part by providing his landlord with a specified number of days of unpaid labour each year.

Bulk Buying Reduces Costs, Increases Quality

As Binns implied, Blacker played an important commercial role as a middleman for the tenants of the estates he managed, by bulk-buying from the large seed merchants and deferring payment (both to him by his tenants, and by him to the merchant) until the following harvest time, making the merchants provide a full nine months’ line of credit. In doing so he in effect provided his tenants with more working capital and an interest-free loan.

He was usually able to obtain the highest quality seeds for the lowest possible wholesale price. By ensuring that his tenants only used top-quality seed, he increased the productivity of their land, with no effort on their part, and also helped to ensure that they would still be able to pay their rent to the estate in hard times. Everyone benefited. He did not charge the tenants the full retail price but made a small handling charge to cover his costs – ‘breaking bulk’ as he called it.

Blacker’s objective was not his own profit. In a letter to his main supplier in London, Wrench & Son of London Bridge, he writes:

“… I have a reliance upon your house and do not wish to trust the shops here for more than a few bags which may be wanting but I hope you will take care that I am put upon the lowest wholesale footing as it would be a pity to make the poor people I take so much trouble for to pay the retail price.”

Later in the same letter he asserts:

“It is not too much to say that the agriculture of Ireland has improved more these last 5 years than it did for the 50 preceding and the improvement for the next 5 years will be, I think, even still greater….according to their progress in green feeding are obtaining twice or three times the produce from their farms.

In another letter to a different seed supplier, in 1837, he writes:

The quality must be the very best. If any failure took place it would ruin all the estates under my care and would destroy me altogether so I beg your best attention. There is often seed sold chemically prepared but by putting the seed into a glass of vinegar it quickly discharges the colour. None of that so prepared will grow. …

No Time For Feckless Tenants

Blacker was no soft touch when it came to tenants in arrears. In April 1834, the Cork Constitution reprinted one of his articles from the Irish Farmer’s and Gardener’s magazine, in which he said:

“… I make it a standing rule never to forgive any arrears whatsoever which would be bad encouragement for those who had regularly paid their rent as it became due.”

He made a very clear distinction between generic reductions in rent across a whole estate during hard times, such as the agricultural slump following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which he supported on the basis that landlords could not be immune to hard times, and individual farmers not paying their rent, for whatever reason, while their neighbours paid.

He then went on to list a number of farmers on the Gosford estate who had been badly in arrears, but through the adoption (not entirely voluntary, one supposes!) of his methods had paid off their arrears and were now in surplus.

Blacker’s Copy-Out Books

PRONI holds Blacker’s ‘copy-out letter’ books for 1832-1849, which contain hand-written copies of every letter he sent in his various land agent roles. Such books were an essential business tool in the days before printers, photocopiers or even typewriters and carbon paper. They include many letters to his cousin Maxwell Close and they give a fascinating insight into both the role of the land agent and into Blacker the man, as well as his methods and the crises and politics of the day.

Unfortunately, only the periods from February 1832 to April 1838 and from March 1846 to April 1848 (his retirement) have been transcribed so far.

Taxation

Rent and taxes were a constant dark cloud over the small tenant farmer. There were two types of local tax, both of which were calculated per acre of his holding. The cess (rates) was levied by the county and was spent on roads and other public works. Tithes were set by and payable to the established church at parish level. Some landlords would collect all three – rent, cess and tithes – and to pass on the latter two to the relevant bodies. Blacker’s letters indicate that he was allowed to keep a 15% commission from the tithes he collected.

Tithes in particular caused festering resentment, especially among Catholics and dissenting Protestants. Why should they be forced to support a fat-cat Church hierarchy with which they had nothing in common, and from which they received nothing? The upper echelons of the established Church were often very out of touch with the privations experienced by such tenants. In contrast, many landlords and agents were often more sympathetic.

Maxwell Close was regarded as an enlightened landlord, concerned for the welfare of his tenants, and trying to raise them out of poverty. Nevertheless, sometimes Blacker had to be a moderating voice. In January 1835 he writes:

“My dear Maxwell, I have just received yours of this morning… in regard to the tenantry… calling upon those which are parishioners of Ballymore for the tithe due at November 1834 and the arrears as per agreement with the Dean and calling upon the tenants of Killeavey parish for the year’s tithe due at same time and in failure of payment to proceed by ejectments…

“Whatever my private opinions may be… you may rely upon a faithful discharge of my duty… but before doing so I… represent to you in the strongest manner that as Dean Carter is only asking the tenants on other estates for payment of the tithe due at 1833 and by his refusing to answer my letter begging such additional time to be allowed for the collection as would enable me to do the same, he shows that he is determined not to accede to my request and you are thereby left the alternation of either advancing the amount due to him for a short time or continuing to appear to your tenantry in the unpleasant light of having taken part against them by making them pay to 1834 when he is only asking 1833.

“… it is my duty strongly to urge you to advance whatever part of the year 1834 I may be unable to collect before 1 January next… Perhaps this may do away some part of the opposition and the matter may blow over without engendering any unpleasant feeling of a lasting nature which… would… destroy the comfort of your residence at Drumbanagher.

“… Dean Carter has refused to grant the Presbyterian clergymen any exemption… heretofore enjoyed… they paid down the amount on the counter… and went away saying they might thank Colonel Close… and would not have had to pay now but for him.

“… I do not venture to dispute the correctness of the information [you] have received as to what has been done on other estates but… my opinion is there is not any one estate in the parish in which either landlord or agent has either forced or attempted to force obedience… except your own. Having said this much I repeat again I shall follow your orders most implicitly. Perhaps I may be able to succeed but I look on the matter in so serious a point of view that I must beg of you to keep this letter and the others I have written safe.

“… I have desired them [Killeavy tenants] to be warned to pay on Tuesday week and shall state your determination to enforce the payment if I find it necessary. I know if the combination is not very strong, they will be afraid to oppose you. It is not easy to calculate the strength until it breaks out, but several have paid and refuse to take any receipt along with the rent saying they were afraid to let it be known they had paid.”

To paraphrase: ‘Times are hard for tenants, yet the Church is utterly unsympathetic. They’re even changing the unwritten rules. If we insist on our tenants paying, it’s Maxwell Close who looks like an uncaring bastard, not the Dean. That’s what the Presbyterian clergy already feel, and we don’t want them inciting their congregations against you. No other landlords in the area have done what you’re contemplating. Feelings are running very high, and if you insist, especially if we eject any tenants, we could have a major rent strike on our hands. You’re the boss, and I’ll do whatever you instruct me to, but please think very carefully! My advice is to pay the Church’s demands in full from your own funds, and then let’s see what we can recoup from the tenants when times are better.’

Blacker And The Great Famine

The spectre of famine3 has haunted Ireland many times in its history. Although less well known than the Great Famine of the 1840s, the famine of 1740-41 killed a higher proportion of the Irish population; estimates vary from a grim 13% to an horrific 20%. The winter of 1740-41, especially the seven-week period known as The Great Frost, was the coldest on record and even destroyed potatoes left to overwinter in clamps. Poor weather in the following summers exacerbated the situation.

Famine returned almost exactly 100 years later. The Great Famine (an Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger) is generally deemed to have lasted from 1845 to 1852. Every area of Ireland was affected when the potato crop, which had by then supplanted oats as the main source of carbohydrates and calories for the Irish labouring classes, was infected by potato blight, Phytophthora infestans, and started to rot in the fields.

Our famous national tuber was introduced to Ireland from South America by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1589.

“No other European nation has a more special relationship with the potato than Ireland. [They were] the first Europeans to accept it as a field crop in the seventeenth century, [and]… the first to embrace it as a staple food in the eighteenth. The potato emerged strongly in Ireland because it suited the soil, climate and living conditions remarkably well.

“What set Ireland apart from other European countries was the way the population took to the tuber – the potato was universally liked. Arthur Young… was impressed by the vast acreage of potato cultivation he encountered. The potato was seen as a safeguard against the tandem social plagues of unemployment, poverty, overpopulation and land hunger. By 1780, at a population level of four million, those afflictions had helped push the potato to dominance. In 1830, young adult males in Ireland were consuming 5 kgs per capita per day – a matter of public record.”4 [9]

The names of the potato varieties grown in the years before the famine are unfamiliar to modern ears; a piece in the Newry Telegraph in 1839 by a Newry seedsman, Mr Buchanan, mentions Alexander Kinmonth as very successfully growing the varieties Prince de Rohan, Scotch Gray, and Lumper. Lumper was the most popular variety in Ireland at the time, but it was unfortunately also the most highly susceptible to the blight which struck just a few years later.

William Greig’s 1820 report made clear that many tenants regarded farming as a secondary activity. Their farm cottages were somewhere to carry out their main activity, linen weaving. The local effects of the famine were magnified as the linen industry was going through one of its periodic slumps, and as the price of food rose steeply due to shortages, the income of most working families dropped severely.

On 7th November 1845, the Mansion House Committee in Dublin wrote to Sir Robert Peel, UK Prime Minister, imploring him to believe that a severe famine was about to happen in Ireland, and urging him to take measures to help avert it. The Newry Telegraph reported on a meeting held in Poyntzpass on the very same day, chaired by Col Close, to discuss:

“… what might appear best to be done under the present alarm as to the disease in the potatoes” and “… receiving and diffusing the best and latest information for economising food from the diseased potatoes and, if possible, preserving what of them at present seems sound from contagion or decay.”

One method recommended by Blacker was to boil diseased potatoes to a pulp, with several changes of water, and then recover and dry the starch.

“It may be made into bread with the addition of meal of any kind, or with cabbage will make excellent culcannon”.

Desperate times!

“Famine? What Famine?”

Some newspapers even denounced the famine, and its attendant diseases, as ‘fake news’. On 20th March 1846, the Tyrone Constitution claimed that Sir Robert Peel was just ‘talking up’ both, to advance his own political career. It also accused the report sent to Queen Victoria describing the situation in Ireland of being one-sided, and of only including submissions from dispensary doctors in areas when the news of increased disease was particularly bad and claimed that fever was generally “the result of the filthy and improvident nature of the people.”

Victim-blaming is an ancient art.

Blacker Prepares For 1846/47

Meanwhile, optimistic that the failure of the 1845 crop was just a blip, Blacker was ordering large quantities of seed potatoes from Inverness for his tenants. With the panic about both real and imagined shortages, the price of basic foodstuffs had risen, and many merchants were stockpiling grain in the hope of even higher prices later in the year.

So Blacker had also purchased a large quantity of oats and advocated setting up a stockpile of Indian corn (maize) meal to force the price down. By 12th July 1846, still optimistic, he advertised 40 tons of oatmeal for sale, only to withdraw it just ten days later as the first signs of blight appeared on the 1846 potato crop.

By late 1846, after two successive potato crop failures, Blacker was thinking deeply about how farmers could hedge their bets. Like all diseases, the blight would eventually run its course – but when? Next year? In five years’ time? Should (or could) farmers stop planting potatoes? Do any varieties seem to be more blight-resistant? How much land should they risk with the crop? Were there specific methods of husbandry that aided or hindered the blight? What other crops should be planted to insure against starvation if the potato crop failed again?

An article written by Blacker addressing all these issues appeared in the Londonderry Standard on 6th November – but had undoubtedly been copied from a local Co Armagh paper. It covered the best way to plant potatoes, how to store seed potatoes for next year, what types of manure to use and how much (over-manuring seemed to be associated with the worst blight outbreaks), how to maximise chances of success by the use of lazy beds and good drainage, how to ‘subsoil’ while preserving fertile topsoil, increasing use of kale and parsnips, best hoeing practice, saving stones from the soil to line deep field drains – etc, etc, etc!

Local Famine Relief Committees

Once the extent and potential impact of the failure of the potato crop became apparent, local Famine Relief Committees were quickly set up. The Poyntzpass committee was convened at the end of the 7th of November 1845 meeting. It included familiar locals such as Alexander Kinmonth, John Bennet, Peter Quinn and Crozier Christy as well as Dr Moorcroft, the Reverends Darby, Gamble, Elwood and Priestley, and Messrs Moody, Madden, Porter, Milne and Allen; naturally, Col Close was chairman. The committee was to meet weekly.

Later in November 1846, Col Close wrote to the Earl of Gosford, County Lieutenant, advising him that famine relief committees had been formed for Poyntzpass and Tandragee. Blacker of Gosford chaired the Markethill committee. His copy-out book shows that he was quick to use his contacts and buying power to secure and import potatoes and other foodstuffs, such as yellow meal (maize flour), from other parts of the British Isles, for the tenants of the multiple estates which he managed.

Blacker vs. The Bureaucrats

An innovative type of famine relief scheme was for landowners to pay their tenants in cash for making improvements to their own holdings – repairing ditches, improving drainage, planting hedges etc. Government funds were made available, from which landowners could reclaim some of their outlay.

Blacker, an intensely practical man, expressed exasperation about the bureaucracy surrounding the scheme – the need to submit detailed plans, including survey drawings, for each proposed improvement, get approval in advance, and to have it inspected afterwards. Writing to the Castle Administration in Dublin about Gosford tenants, Blacker says:

“I am informed… that before any grant… can be sanctioned by you… a report stating the present and improved value of the fields to be drained with a plan estimate and specification must accompany the application and further that the fields intended to be drained should be marked upon the ordnance survey. If such requirements are insisted on, I apprehend the present Act will be as great a failure as its predecessor the Million Act5 as far as the North of Ireland is concerned…

”… the ordnance survey of the County Armagh has not been laid down in fields and the scale is so minute that it will be exceedingly difficult so accurately to specify each particular field… there is the further objection that if this even was accomplished the record so made would not be of any certain value as the proposed drainage there stated might never be carried into effect by the tenant.

“… the number of his Lordship’s tenants in the county of Armagh are somewhere about 1,100 each of whom would have the privilege of draining one or two fields, besides which in his estate in county of Cavan there are 400 to 500 more. You must therefore be aware gentlemen that to insist upon such a condition… is at once to put a veto upon the whole operation of the Act, for the surveyors could not be found to comply with the demand in any reasonable time and the expense and delay in the first instance and again in the verification survey to be made by your officers will naturally deter most people from embarking in any improvement…

“… to make detailed plans estimates and specifications for 2,000 or 3,000 distinct fields would seem to be an unnecessary and unreasonable requirement inasmuch as the drains are universally made up and down the slope at different depths and distances apart, according to the nature of the soil when opened up, until which is done neither depth distance or expense of making the drains can be accurately ascertained… ‘

“All that government can claim interference in is to see that there is actual work done for the money and that it is laid out for the object stated in doing which there can be no difficulty as the drains will speak for themselves and any competent person can easily judge whether they should cost the sum charged for them.

“I believe I was the first person who ever proposed that government should advance money to individuals for the purpose of thorough drainage… I venture to propose that the Board of Works should… only require… the names of the townlands in which the proposed drainage was intended.”

It was a totally impractical scheme, dreamed up by isolated bureaucrats without a clue how it could be implemented – sounds familiar?

The 1846 Act was extended for another 12 months in 1847, and, notwithstanding Blacker’s reservations, Bell and Watson6 report that “By 1850, over £3.5 million in loans had been applied for… 20,000 labourers employed in drainage, and 74,000 acres had been reclaimed.”

In another letter, to Lord Gosford, Blacker discusses the feasibility and cost of setting up a tile works to make clay tiles to create covered drains in fields.

Blacker was generous with his money, as well as his advice, in support of famine relief. In July 1849, his name appears in the Dublin Evening Post’s list of the latest donors to the General Central Relief Committee. He gave £50 (his second donation), a sum matched only by Arthur Guinness & Sons.

Retirement

In 1846, Blacker delegated the management of the Dungannon School estate to his assistant William Wann, who had worked for him for 21 years, had formerly managed the estate’s finances, and who had recently deputised for him there during a prolonged 3-year illness.

After Blacker’s retirement aged about 72, in early 1848, and his resignation as Agent for both Gosford and Drumbanagher, the Newry Telegraph published two very appreciative Public Addresses from his Poyntzpass and Markethill tenants, a few days apart. The Poyntzpass tenants’ address said:

“ESTEMED AND RESPECTED SIR,

Your retirement from the Agency of Colonel Close’s Estates has affected with the deepest regret the Tenantry residing thereon, and we now desire to express our sorrow that you should have found it expedient to withdraw from public life.“The activity, energy, and talent, which distinguished your useful and prominent career for now upwards of a quarter of a century, had led us to hope a gracious Providence would have enabled you to have acted for many years to come as our true friend, wise counsellor and upright and impartial Agent…

“In your hands authority was not exercised merely in collecting or enforcing the payment of rents, but combined with unceasing exertions to improve our moral and agricultural condition… you have been the means of importing that information in agricultural pursuits which has enabled us to exhibit so marked an improvement in the cultivation and management of our farms… we became ambitious to excel our neighbour in the honourable rivalry of being the possessor of the neatest cottage, and the most productive farm, tilled according to modern and approved principles.

“When you became our Agent, our fields were undrained, the subject of the old exhausting system of eternal cropping with white grain, now and then relieved by a potato crop always imperfectly manured, for no cattle were house-fed as we were ignorant of green cropping; but through your kindness and preservation, combined with a simple, plain and familiar style of conveying instructions, by pamphlets and otherwise, we now understand the value of draining and subsoiling, the superiority of turnip manure to all others; but above all, the absolute necessity of the rotation of crops… ”

In that age, such public praise of the rich and powerful by those whose lives they controlled was common, and could be sycophantic and cynical, but in the case of William Blacker of Gosford, I have no doubt that it was entirely genuine and heartfelt. It is a good summary of the man and his methods.

Blacker’s reply to the Markethill tenants’ address, and published immediately below it, mentions, as well as the Gosford estate, the estates of the Earl of Charlemont, Sir George Molyneaux and Captain Cope. So presumably he had also been Agent for these as well until recently.

You can download a full account of the addresses here.

The Newry Telegraph agreed with Blacker’s tenants; in May 1848 it proclaimed:

It is not many years since… small farmers were considered as being one of the greatest drawbacks on the improvement of this country… A change for the better has now taken place and the small-farm system… is now, by many, looked upon as far from being such a curse… At the time when Mr Blacker first published his plans for improving the small farmers of Ireland, by a system of agricultural instruction, his views were looked upon by many as being visionary and altogether unfit for affecting the desired end;

… yet what do we now find to be the case? Simply, that it is adopted not merely in a private manner on a few estates, but that it has become a national undertaking. Instead of a few isolated cases, we now have the “apostles” of peace and plenty scattered over the length and breadth of the land, and all classes, from the Peer to the peasant, eagerly listening to their instructions… [It is] already telling on the general improvement of the condition of our once neglected and despised small farmers. It must be a source of high gratification to Mr Blacker to see such fruits springing from his labours, and to find his views so extensively acted upon as they now are. We may date the improvement of agriculture in this country from the publication of his “addresses” and if any man ever deserved the gratitude of his fellow-countryman, it is William Blacker.

It is likely that Blacker was directly succeeded as Drumbanagher agent by Peter Quinn. Quinn lived at Acton House from the early 1840s and had been actively involved in the D&AFS from that time, as a judge. He would have been very well acquainted with Blacker and his methods.

Final Illness & Death

The newspapers reported that on 4th July 1850, Blacker had been ‘struck down’ and was now paralysed; it was most likely as a result of a stroke.

Several months later, on 20th October 1850, William Blacker of Gosford died at his home, a fine Georgian house in Charlemont Place on The Mall in Armagh. He was in his 75th year, and had never married. The death of “this distinguished agricultural writer and economist” was widely reported in British and Irish newspapers.

Newspapers reported that Blacker was buried “in the family vault at the parish church of St John, Mullaghbrack” where his older brother Samuel Blacker had been vicar for over 20 years until his death two years earlier. But there is no Blacker family grave or tomb in the churchyard so it has been suggested that the vault may be beneath the beneath the Blacker family pew, close to the plaque shown. However, internal parish church burials, although commonplace in England, were very unusual in Ireland. So, for the time being, William Blacker’s exact final resting place is a mystery.

The funeral was attended by the cream of Co Armagh society, and clergy from practically every denomination. The pallbearers included the Earl of Gosford, distant relative and namesake Col. William Blacker of Carrick and Sir James Stronge.

William Wann succeeded Blacker as Gosford agent on his retirement and remained in post until his death in 1880, aged 67. Like his great mentor, Wann was also buried in Mullaghbrack churchyard.

Blacker’s Legacy

While Blacker’s name may not be known to many of us today, it would have been both familiar to, and respected by, all levels of society 200 years ago; his methods increased the prosperity of landlords and tenants alike.

Agricultural change carried on apace after his death. An article in the Downpatrick Recorder from 1st February 1868 commented:

“It is not much more than 30 years since attention began generally to be turned in Ulster to the subject of scientific rotation of crops, of which the late Mr William Blacker, of Markethill, was one of the earliest and most persevering exponents. Nowadays every farmer here pursues, with more or less regularity, the rotation system. Farms have grown larger… The small holdings of a few acres, which were such an obstacle to agricultural improvement… are gradually disappearing… the occupiers themselves have found a more prosperous lot across the Atlantic or in some of the centres of manufacturing.”

As you travel the roads of Co Armagh, the imprint of William Blacker of Gosford is all around you, in the form of well-drained fields, straight hedges and large, prosperous farms. Few individuals have done more to shape and improve our countryside.

- One of three huge private Indian armies under the control of the British East India Company. ↩︎

- A cottier was a tenant whose rent was paid partly or wholly by the number of days of unpaid labour he provided to the landlord. ↩︎

- See “Loughbrickland Famine Correspondence”, John J Sands, BIF Vol 1, 1987

Also “Pre-Famine Poverty in Aghaderg”, also by John J Sands, BIF Vol 3, 1989 ↩︎ - See “History of The Potato in Ireland”, World Potato Congress, Dublin 2022 ↩︎

- The Drainage Act of 1846, which allocated £1 million for famine relief projects. The British government had determined that paying workers for improvement projects in cash was preferable to handouts, and that these projects should almost exclusively consist of surface drains. Sub-surface drains were not funded – possibly because of the difficulty in detecting fraudulent claims by inspecting them. ↩︎

- “A History of Irish Farming 1750-1950” by Jonathan Bell & Mervyn Watson, 2008, Four Courts Press ↩︎