William Hare, the notorious murderer, appears to have been born about July 1801 in the townland of Moneyquin, Co Armagh, about 13 miles due west of Poyntzpass, to Patrick O’Heere and Alice Mallon. In his youth he tended horses which pulled the lighters on the Newry canal near Poyntzpass.

After having killed one of his employer’s horses in a fit of rage, he fled to Scotland and ended up in Edinburgh. He worked as a labourer, including on the Union Canal, and stayed in a lodging house in the West Port area, close to the castle, run by James Loag (or Log) and his wife Margaret (nee Laird). Margaret was also Irish, was said to hail from near Derry, and was known as Lucky. James Loag died in 1826 and Hare married his widow just six months later, and together they ran the lodging house.

Hare and his new wife became friends with William Burke and his partner Helen McDougal in November 1827. Late that year, an old man called Donald, who owed the Hares £4 in back rent, died in the lodging house. To recoup the rent, the Hares opened his coffin, removed and hid the body, filled the empty coffin with waste material and nailed it shut again, then with Burke’s help sold the body to surgeon Alexander Knox for dissection demonstrations to medical students.

However, the foursome soon realised that instead of waiting for people to die, it would be much more profitable to simply kill them, and soon they became regular suppliers of cadavers to Knox, who conveniently didn’t ask why they had such a steady supply of corpses! In just nine months, they carried out at least 16 murders in the lodging house and in Burke’s house in the same street. The surgeon paid them £8 for a body in the summer and £10 in winter; winter bodies lasted longer! Their modus operandi was to get a victim blind drunk and then smother them while they slept. The bodies could then be delivered to Knox with no outward signs of the cause of death.

It was originally thought that the four were grave robbers, so they were initially called’resurrectionists’! However, they were simply serial killers.

When the four murderers were arrested on 1st November 1828, Hare quickly turned Kings’ Evidence and so despite having been complicit in at least twelve of the murders, avoided prosecution and any form of official retribution. In doing so, he also protected his wife, as in those days a married person could not give evidence against their spouse.

The trial of Burke and McDougal began at 9.40am on Christmas Eve 1828 and continued through the following night. They were initially charged with three murders – Mary Paterson, James “Daft Jamie” Wilson, and Mary Campbell, but only tried for the murder of Campbell. When Hare was questioned as a witness, many of his answers were in the nature of “no comment” so that he did not incriminate himself under oath.

At about 9.30am on Christmas Day, after a mere 50 minutes deliberation, the jury found Burke guilty and the case against McDougal not proven. Burke was sentenced to be hanged, and the judge also specified that his body should be publicly dissected.

Soon after the verdicts were announced, McDougal was set free. Burke was hanged before a huge crowd estimated at 20,000 in Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket on 28th January 1829, and his body was dissected by Professor Alexander Munro in Edinburgh University four days later. The public demand for tickets for the dissection was so enormous that there were near-riots.

Just before the Hares were due to be released, a civil case for £500 compensation was brought by by the mother and sister of ‘daft Jamie’ Wilson. On 21st January, Hare lodged a petition to be released, but judgment was deferred for want of precedent. There were long and complex arguments as to whether the immunity given to Hare over the murder of Wilson also protected him from civil prosecution.

Margaret’s release was authorised on 24th January, but she did not leave prison until the 26th. On 8th February she was in London Street, Edinburgh, with her child, when she was recognised and the police had to be called to protect her from the mob. By 10th February she had arrived in Greenock, where she intended to board a steamer for Derry, but a mob prevented her from embarking, and once more the police took her into protective custody. On 12th February, she finally boarded ‘The Fingal’ bound for Belfast.

Also on 12th February 1829, William was finally released. His continued presence in Ebinburgh would cause civil unrest, so the authorities exported that problem by almost immediately putting him on the mail coach to Dumfries. On arrival he tried to stay at The King’s Arms Inn, but such a huge and angry mob assembled he had to be spirited away to the local jail for his own safety. The mob tried to attack the jail, and when they failed, broke all the windows in the adjacent courthouse!

In the last week of February, newspapers carried numerous reports of Hare being spotted, and chased by a mob, in places as far apart as Carlisle, Tyneside, Stockport and Kilkenny! But all of these seem to be cases of mistaken identity.

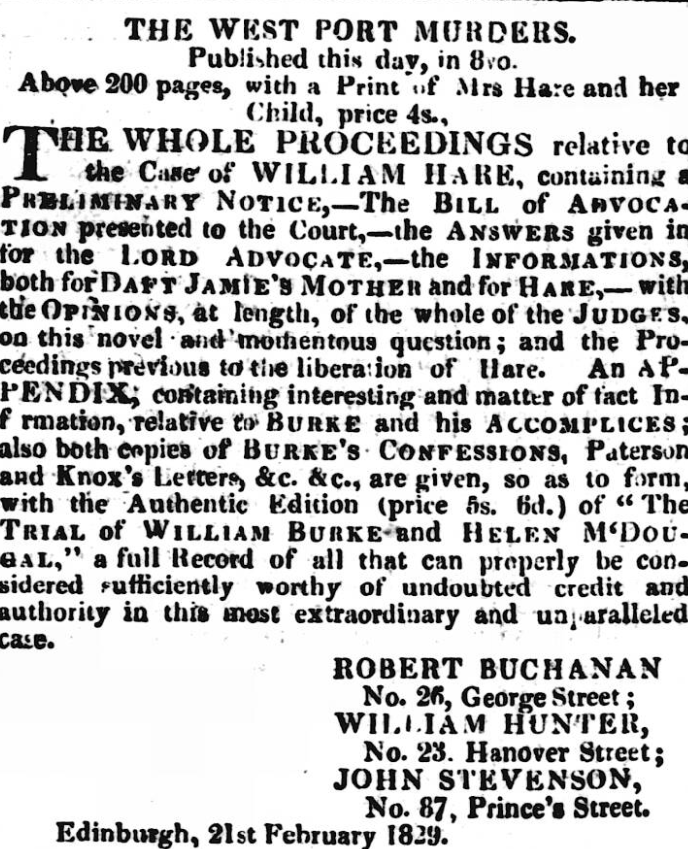

The local Edinburgh press were not slow to cash in on the sensational case of the West Port Murders. By late February, printed account of the murders and the trial, more than 360 pages long, was on sale!

By the end of March 1829, the Hare family seem to have reunited in Ireland. Hare’s notoriety had preceded him and The Scotsman newspaper reported that on 27th March he was recognised in a pub in Scarva, a place that would have been very familiar to him from his time working as a horse-boy on the Newry Canal. But it also meant he was well-known to the locals.

“Hare the murderer called in at a public house in Scarva, accompanied by his wife and child, and having ordered a noggin of whiskey, he began to inquire for the welfare of every member of the family of the house…However, as Hare is a native of this neighbourhood he was very soon recognised, and ordered to leave the place immediately, with which he complied, after attempting to palliate his horrid crimes by describing them as having been the effects of intoxication. He took the road towards Loughbrickland, followed by a number of boys, yelling and threatening in such a manner as obliged to him to take through the fields, with such speed that he soon disappeared, while his unfortunate wife remained on the road, imploring forgiveness, and denying, in the most solemn manner, any participation in the crimes of her wretched husband…He was born and bred about one half mile distant from Scarva, in the opposite county of Armagh; and shortly before his departure from this country, he lived in the service of Mr Hall, the keeper of the eleventh lock, near Poyntzpass. He was chiefly engaged in driving the horses, which his master employed in hauling lighters on the Newry Canal. He was always remarkable for being of a ferocious and malignant disposition, an instance of which he gave in killing one of his master’s horses, which obliged him to fly to Scotland where he perpetrated those unparalleled crimes.”

The report seems to be wrong about where Hare was born. It was the last published report about his whereabouts.

Margaret Hare’s protests of innocence were highly disingenuous; the evidence offered at the trial of Burke and McDougal portrayed her as a willing, even enthusiastic, participant in the killings. Burke even claimed during the trial that Margaret had urged him to murder his partner, McDougal!

The Scotsman reported in July 1829 that the Hares’ old lodging house was now a ‘heckling shop’ where the final stages of flax processing were caried out.

Hare and his family were rumoured to have ended up in the workhouse in either Newry or Kilkeel.